- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organizational Behaviour and Gender

About this book

Organizational Behaviour and Gender provides an alternative to the gender silence of the standard OB textbooks. This Second Edition updates and expands the text's coverage and employs the most recent research findings to portray the world of work in a realistic manner. Organizational Behaviour and Gender is a comprehensive text. The text examines some of the assumptions that have been made about women at work - for example that women's 'difference' is rooted in biology and that women and men have contrasting (and even polar opposite) skills and attitudes. The text considers the key topics in OB (such as selection, assessment,leadership and motivation) to test such assumptions. The book describes the reality of working life for women. It examines issues of low pay, part-time working, family responsibilities, home working and horizontal and vertical job segregation. It asks whether inequality of opportunity comes about because of actual gender differences or from prejudicial expectations and thinking. The last chapter is about sex and sexuality in organizations. Sexual behaviour in organizations is pervasive but is rarely discussed in OB textbooks. This chapter describes the masculine and heterosexual business environment and examines the issues of work romances and sexual harassment. The text provides numerous learning aids (including discussion topics and chapter questions) to assist both the lecturer and the student.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Organizational Behaviour and Gender by Fiona M. Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Men and Women’s Place at Work and Home

‘The Master Rules’

Our views of work take, as their starting point, the male-as-norm. It is, for example the norm and typical that managers are male. A quote from an Institute of Management report reinforces this when it says ‘The typical manager is male, married and earns between £31,000 and £40,000 a year’ (Institute of Management, 2001).

It is easy to think of work typically as an activity that takes place on a daily basis, that you ‘go out to’, is paid employment, is full time, lasts a lifetime, and is an uninterrupted commitment. But this model of work would describe a male model of work. The male-as-norm model and the ensuing attitudes constitute significant occupational and employment barriers for women. Views of masculinity and femininity are bound up with the dichotomy between home and work. Since work and home are contrasted, housework is typified as non-work, women’s paid work is regarded as marginal and temporary and working wives and mothers are ‘problems’. Where attitudes like ‘men go out to work while women stay at home’ are generally accepted common attitudes, they are subtle but highly effective barriers. No one questions the desirability of holding these views and few challenge the implicit discrimination.

A model that might adequately describe women’s work is different to the male model of work. It would need to take account of both home work and paid work. Women’s paid employment does not exist in isolation. It is inextricably linked to their unpaid work in the household and community. Women all over the world have primary responsibilities for the non-material well being of their families. This is the case for some men too. Any employment entails a trade-off which involve implicit and explicit costs, particularly for married women and women with children. How can men and women’s work be described?

Some Facts about Men, Women and Work

To begin let us look at men and women’s place at work and home, drawing from employment statistics and sociological studies so that we have an informed perspective of their position in employment and home. Women make up 44 per cent of employed people in the UK (Cabinet Office, 2000). Not all work is paid and outside the home; there is housework and voluntary work. It is impossible to estimate activities in the ‘informal’ economy (work in informal paid work, voluntary work and in the domestic field) but women’s participation in the formal economy has steadily increased during this last century. Work has gained a greater place in women’s lives in the western world. White, middle class, highly educated women have made considerable inroads into careers once dominated by men (Adkins, 1995). These gains have been less pronounced for less well educated, working class women, particularly those from ethnic minority backgrounds (Anderson, 1997).

Employment for men has fallen over the last two decades as employment for women has increased. For example between 1984 and 1999 the proportion of men who were economically active declined from 88 to 84 per cent while the proportion of women increased from 66 to 72 per cent (EOC, 2001). But it must be appreciated that rates of unemployment and non-employment are not caused by female employment. These are parallel and not competing trends. For example between 1992 and 1995 there was a 12 per cent fall in the proportion of male employees in craft and related occupations compared with an 18 per cent fall for women (Social Trends, 1996).

Part-Time Working

Many women in Britain work on a part-time basis. Eighty three per cent of part time employees are women (EOC, 2001). Part-time work is attractive to both married women employees and to employers for the flexibility it gives. It gives employers flexibility in scheduling work. Many working activities experience peaks and troughs throughout the day and week, for example at check-outs in supermarkets, in betting shops (where business is concentrated around 3-4 hours in the afternoon, Filby, 1992) and in transport. Part-time working has expanded with skill shortages and demographic changes; for example the level of male part time working rose faster between 1984-1997 than that for women (Social Trends, 1998 p.80). The recessions of the early 1980s and the early 1990s accelerated the shift towards part-time employment patterns.

While women make up the overwhelming majority of part time workers, they do not necessarily prefer part-time work; for many it is a matter of compelled circumstance, like domestic commitments, not a matter of preference. As long as women remain largely responsible for work involved with the maintenance of the family and home life, there will be a limit on how much work they can do outside the home. Some studies have found young, single, educated women working part time because they cannot find a full time job (Walsh, 1999). Of those men who work part time, nearly four fifths are under 25 and are students or still at school. Almost half of the men aged 25 to 44 who work part time do so because they too cannot find full time jobs (EOC, 2001). There are usually serious financial consequences of part time working like lost income and pension eligibility.

Part-timers are clustered in low-pay, low-skill categories of work. The average hourly earnings of part-timers are not much more than half those of the average male full-timer. The largest concentrations of women working part-time are in the service industries (education, retail, hotels and catering, medical and other health services). In several of these industries the expansion of part-time employment occurred while full-time employment contracted. The rationale for the expansion of part-time work for women was to enable them to combine paid employment with domestic responsibilities. But it is possible to increase women’s economic activity without increasing the number of part-time jobs. Provision of better childcare facilities and paternity/maternity benefit may help. There is a shortage of part time positions at senior levels in organizations and so some women are forced to work at lower levels due to lack of part time positions at more senior levels (DfEE, 1997).

Self Employment

About 74 per cent of the self-employed are men and 26 per cent women in Britain. Again women are more likely to be working part time in self-employment than men (50 per cent female, 9 per cent male, EOC, 2001). There has been no widespread research into business survival rates but small-scale studies suggest that once established businesses run by women are more likely to survive than those run by men. This may be because women’s businesses tend to grow at a slower rate than men’s do (EOC, 2001). Research also suggests that women are drawn to business ownership in order to gain recognition (Hisrich et al., 1997).

Ethnic Minority Women and Men

Ethnic minority people have lower employment rates than white people and women from ethnic minorities have lower employment rates than their male counterparts (EOC, 2001). Many men and women from ethnic minorities work in family firms- the corner shop, the Cypriot cafe and the Chinese takeaway.

Research analysing black and ethnic minority women managers’ and professionals’ position is just beginning. According to recent British labour force data, 9 per cent of ethnic minority females in the UK are found in the category ‘Professional, Manager, Employer, Employees and Managers - large establishments’ compared to 11 per cent of white females (Davidson, 1997). Relative to white women, black and ethnic minority women continue to be under-represented in higher-grade employment (Bhavnani, 1996). Black women are less likely than white to become managers, are on lower grades within the same occupation, are more likely to do shift work and are more likely to be unemployed. Black women and men who do become managers tend to work in small firms where the label manager may connote different status and responsibilities compared to being a manager in a large organization (Breugal, 1994). As managers they are more likely to be self employed owner-managers of very small units and are more likely to be in the cash strapped public sector (Bhavnani and Coyle, 2000).

There are a number of myths that perpetuate everyday talk about the place of women and men at home and work. We will now look at the fact and fiction in more depth.

Myth 1: Equality Of Opportunity Has Been Assured By Legislation

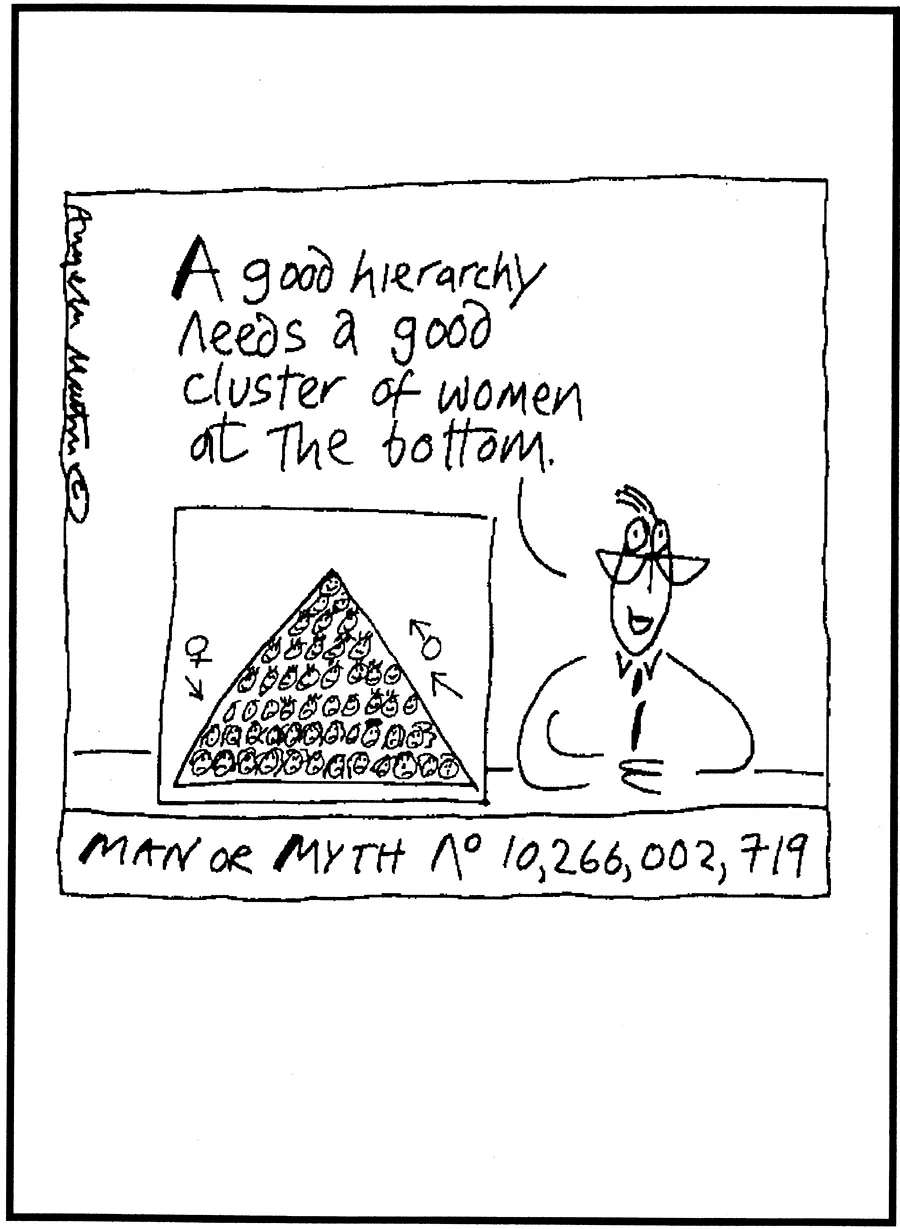

Despite more than two decades of equal opportunities legislation in Britain and activities by organizations to improve equal opportunities, it is very evident that women are still clustered in certain sectors of the economy and at the base of organizational hierarchies. Additionally, in spite the adoption of equal opportunities policies in many organizations, little progress seems to have been made. For example 93 out of 100 university professors, 96 out of 100 general surgeons and 96 out of 100 company directors are men (Waters, 1998). Women report that a range of obstacles impede their progress that include childcare arrangements, lack of flexible working and access to training. Occupational segregation is probably the largest barrier women face. Examples of segregation exist in almost every industrial and service sector within the economy.

Segregation in employment is by ethnicity as well as gender, with complex patterns as these intersect. Black women are subject to greater restrictions in then-access to good employment conditions and pay than any other groups. Homeworkers of all races are extremely badly paid. Let us look at occupational segregation for all women in some detail.

Occupational segregation exists where women are disproportionately represented in certain jobs relative to their overall proportion in the workforce, and there are varying degrees of segregation. It refers to the division of the labour market into predominantly male and female occupations and occurs along two dimensions, horizontal and vertical.

Horizontal occupational segregation occurs where men and women are most commonly working in different types of occupation, for example where women predominate in occupations such as data preparation clerks, receptionists and chambermaids and men in occupations such as computer operators, engineers, carpenters and kitchen porters. Horizontal segregation is maintained by the recruitment of men and women to different jobs. Jobs become sex typed into masculine or feminine jobs. Driving jobs are, for example, sex segregated. While it is common for both men and women to drive cars for domestic reasons, between 95 and 99 per cent of driving jobs in the EU are done by men (Whittock, 2000). Crane driving is normally considered a male job while reception work is female. Once established, the pattern of occupational segregation by gender becomes fixed. Jobs are constructed either as masculine or as feminine in a manner that becomes accepted as normal by both men and women. In manual work ‘skill’ is socially constructed so that jobs that involve tasks seen as masculine, like driving, are seen as more skilled than jobs that involve feminine dexterity, such as sewing.

Vertical segregation describes another structuring, where men are most commonly working in higher-grade occupations and women in lower grades. This happens even in so-called women’s occupations, While women account for around 90 per cent of all qualified nurses, men hold disproportionately more higher-grade posts relative to their overall numbers (Evans, 1997a; MacDougall, 1997). Furthermore men achieve these senior posts in a comparatively short space of time compared to women. The men appear to be on a ‘glass escalator’ having a smooth and inexorable rise to senior management (Williams, 1992) Research has shown it takes 11.4 years for a woman compared to 6.9 years for a man to reach first Nurse Officer post (Wyatt and Langridge, 1996). Male nurses are encouraged to apply for promotion while some women’s domestic commitments are interpreted by interviewers as constituting potential difficulties (Evans, 1997b)

White collar work can be seen to be vertically segregated along gender lines with, for example, women performing the bulk of clerical and secretarial work and men managerial and higher professional work. The ‘glass ceiling’, the barrier based on discriminatory attitudes or bias that impede of prevent qualified individuals from advancement, is very much in place in management, particularly in senior management. According to the Cabinet Office (2000), women in the UK hold just 18 per cent of all management positions and 3.6 per cent of directorships. Only one woman made it to CEO in the FTSE 100 list and she was the only female in that list paid more than £lm in 1999 (Singh et al., 2001). The situation is similar in many other countries. For example in Germany women are estimated to fill only 25 per cent of managerial positions (United Nations, 1998) and only 5 per cent of senior management jobs (Neumann, 1998).

For those who would like to argue that the situation for women managers is improving with ti...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1 Men and Women’s Place at Work and Home

- 2 Perceiving Men and Women in Organizations

- 3 Learning and Socialization

- 4 Motivation

- 5 Leadership

- 6 Personality

- 7 Sex, the Body and Sexuality in Organizations

- AppendixSexual Harassment: Anne’s Experience

- Index