- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire

About this book

While much has been written on Marcel Duchamp - one of the twentieth century's most beguiling artists - the subject of his flirtation with architecture seems to have been largely overlooked. Yet, in the carefully arranged plans and sections organising the blueprint of desire in the Large Glass, his numerous pieces replicating architectural fragments, and his involvement in designing exhibitions, Duchamp's fascination with architectural design is clearly evident. As his unconventional architectural influences - Niceron, Lequeu and Kiesler - and diverse legacy - Tschumi, OMA, Webb, Diller + Scofidio and Nicholson - indicate, Duchamp was not as much interested in 'built' architecture as he was in the architecture of desire, re-constructing the imagination through drawing and testing the boundaries between reality and its aesthetic and philosophical possibilities. Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire examines the link between architectural thinking and Duchamp's work. By employing design, drawing and making - the tools of the architect - Haralambidou performs an architectural analysis of Duchamp's final enigmatic work Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas... demonstrating an innovative research methodology able to grasp meaning beyond textual analysis. This novel reading of his ideas and methods adds to, but also challenges, other art-historical interpretations. Through three main themes - allegory, visuality and desire - the book defines and theorises an alternative drawing practice positioned between art and architecture that predates and includes Duchamp.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marcel Duchamp and the Architecture of Desire by Penelope Haralambidou in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

1.1 Introducing Marcel Duchamp

How does an architect write about an artist? In May 1937 an innovative visual essay, part of a series entitled Design-Correlation, was published in the American monthly magazine Architectural Record.1 The essay by the Austrian-American architect Frederick Kiesler was a close analysis of a seminal work by French artist Marcel Duchamp entitled The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même), 1915–23.2 Composed on two large glass panes arranged vertically on a frame and using materials such as lead foil, fuse wire, and dust, the work is better known as the Large Glass. It combines meticulously plotted drawings in perspective, as well as forms deriving from chance operations and is accompanied by a set of notes that allude to an allegorical amorous exchange between a ‘Bride’ and her ‘Bachelors’ (fig. 1.1).3

Kiesler’s essay is possibly the first introduction of Duchamp’s complex work to an architecture audience.4 In a letter to Kiesler, Duchamp’s reaction was jubilant:

How you have surprised me! It was a great pleasure to read your article in the 5 extracts of the Architectural Record—firstly the wit of the article, then your interpretation and the way you present your ideas! Thank you for being prepared to look at the glass with such attention and for clarifying points that so few people know about.5

Although he always welcomed interpretations of his work by others, Duchamp is particularly taken by the esprit (lively intelligence, wit) of Kiesler’s essay, his original interpretation and innovative visual presentation. But what were the points that Kiesler was able to clarify that so few people know about, and how was he able to do so?

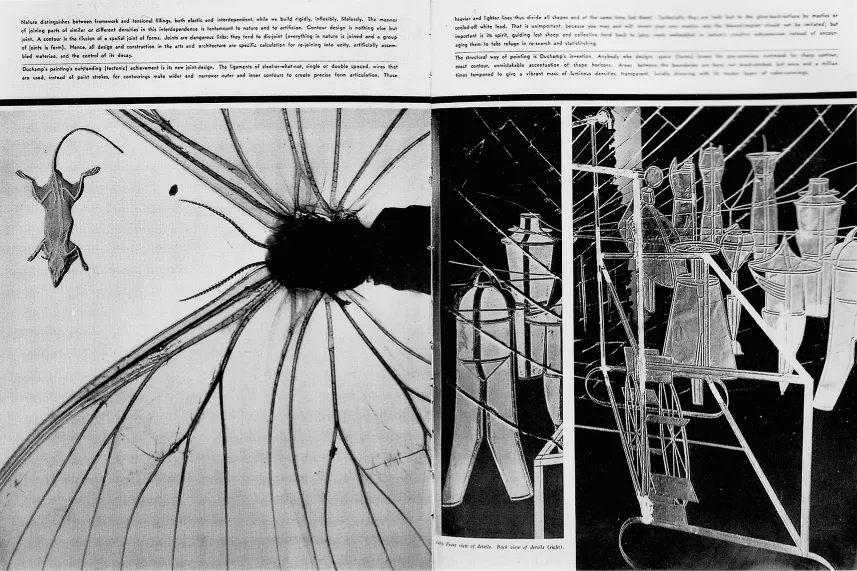

Disappointed with previous photographic representations of the Large Glass, which show the work intact before its infamous accidental shattering in transit, Kiesler commissioned American photographer Berenice Abbott to take new photographs after Duchamp’s ‘restoration’ in 1936.6 Abbott’s photographs depict the Large Glass from the front, but also at an angle and from the back and reveal its visceral texture, absent from earlier photographs. Although these images are the focal point of the essay, Kiesler does not present them conventionally, but cuts, collages and juxtaposes them with images depicting traditional stained glass construction details, a photogram of a leaf, and X-ray images of a bat and mouse. By presenting the photographs this way and employing typography and drawing, Kiesler’s primary mode of interpreting the Large Glass is pictorial.7 In his photographic juxtapositions the jagged strokes of the cracks on the Large Glass join with the lines of the radiographs and the seams of the stained glass patterns to form an original (re-)drawing of Duchamp’s artwork (fig. 1.2).

Appearing at the margins and separated by lines, the text compliments the images in the form of extended captions. In awe of Duchamp’s work, Kiesler calls the Large Glass a ‘masterpiece of the first quarter of twentieth-century painting’ but his primary aim is to establish its significance as architecture: ‘Architecture is control of space. An Easel-painting is illusion of Space-Reality. Duchamp’s Glass is the first x-ray painting of space’; and later: the Large Glass ‘is architecture, sculpture, and painting in ONE’.8 Focusing primarily on its use of glass, the only material that at once expresses surface and space – which he sees as an enclosure that at the same time divides and links – he advocates its ‘structural’ innovations as an ‘outstanding (tectonic) achievement’.9 He then embarks on a description of ‘architectural’ details, linking the work to both medieval technologies of stained glass and to cutting-edge radiography, a connection assisted by his forensic arrangement of Abbott’s photographs.

1.1 Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915–23. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Bequest of Katherine S. Dreier. © Succession Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2013.

1.2 Frederick Kiesler, page spread from ‘Design-Correlation: Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass’, published in Architectural Record.

Kiesler warns his architect readers: ‘Those who think only in “practical” meanings: dollars and cents, brick and mortar, jobs and publicity – would do well to turn to the very last page of this section.’10 He concludes the essay by connecting his interpretation of the Large Glass to contemporary technological innovations in architecture and the construction industry, perhaps as an attempt to comply with pressure from the magazine publishers; Kiesler’s pseudo-technological musings, in this and previous essays in his Design-Correlation series, were not always to the taste of the greater part of the magazine’s readership.11 The final page presents a second reworking of the Large Glass through photographic collage, borrowing images from research into glass technologies, including the use of metal framed glass as partition by German-American architect Mies Van der Rohe; drawings on translucent glass; testing on bullet-proof glass; a woman looking through a circular hole in transparent plastic; and directly below a group of five men in suits standing on sheets of glass to test their resistance. Deriving from unrelated sources and aimed at a dry architectural audience, the collage portrays visual themes strongly associated with the Large Glass: framing and drawing on glass, shooting and breakage of panes of glass, and a ‘Bride’ figure above with ‘Bachelors’ below. Unexpectedly and perhaps unintentionally, the last page is another faithful ‘architectural’ portrayal of Duchamp’s work.

Duchamp’s genuine pleasure with the essay points to an approval of Kiesler’s reading of the Large Glass as an architectural construction. Seeking to produce a work that is ‘not of art’, Duchamp might have welcomed Kiesler’s review of the Large Glass as a work ‘of architecture’ instead.12 Widely overlooked, Duchamp’s interest in architecture exists not only in his construction of the blueprint of desire underpinning the Large Glass, but also in his many artworks replicating architectural fragments, such as doors, windows and mantelpieces, as well as his groundbreaking, unconventional exhibition designs. So the wit, original interpretation and satisfying visual presentation that Duchamp appreciated in the essay might be connected with Kiesler’s approach to the Large Glass as architecture. I argue that Kiesler’s architectural interpretation was able to grasp a novel dimension of the Large Glass, which genuinely surprised and delighted Duchamp.

In an unpublished dissertation, ‘Critiquing Absolutism: Marcel Duchamp’s Étant donnés and the Psychology of Perception’, American scholar Linda Landis points out a striking detail that distinguishes Kiesler’s analysis from perhaps every other interpretation: his ‘complete failure to mention the Bride and the Bachelors’.13 Kiesler addresses this omission in his essay:

We look at it not to interpret the bio-plastic exposition of the upper half of the picture or of the mechanomanic lower part; such physio and psychoanalysis will be readily found here and there, now and later—but I bring to the technicians of design-realization the teaching of its techniques.14

Kiesler chooses not to address the allegorical subtext of the amorous exchange between the Bride and the Bachelors and presents instead an alternative allegory:

To create such an X-ray painting of space, materiae [sic] and psychic, one needs as a lens (a) oneself, well focused and dusted off, (b) the subconscious as camera obscura, (c) a super-consciousness as sensitizer, and (d) the clash of this trinity to illuminate the scene.15

Describing the creative act as a photographic camera, Kiesler infers that the image on the Large Glass is a snapshot of the creative mind in action. Duchamp also insinuates this allegorical interpretation – albeit couched in poetic and cryptic language – in his notes for the Large Glass, to which Kiesler did not have access prior to composing his essay.16 At a further allegorical level, Kiesler’s terminology clearly alludes to the id, ego and superego, the three elements of Sigmund Freud’s structural model of the psyche.17 So in Kiesler’s analysis of the Large Glass the ego is ‘a lens (a) oneself, well focused and dusted off’, the id is ‘(b) the subconscious as camera obscura’ and the superego is ‘(c) a super-consciousness as sensitizer’. Blending the allegory of photographic processes with psychoanalytic theory, Kiesler proposes Duchamp’s work as an ‘architecture of desire’. I suggest that when Duchamp declares in his jubilant letter that Kiesler clarifies ‘points that so few people know about’ he refers to this particular passage.18

Related to the Large Glass and its photographic camera imagery, this description is also a fitting narrative for the viewer’s experience in front of Duchamp’s other major piece, Étant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau, 2° le gaz d’éclairage … (Given: 1. The Waterfall, 2. The Illuminating Gas …), 1946–66, or Given (fig. 1.3).19

Closely connected with the themes governing the Large Glass, Given is a three-dimensional assemblage, a diorama permanently installed in a room at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Hidden behind a wooden door and portraying a brightly lit and explicitly pornographic scene, the diorama is visually accessed through two peepholes. In the experience of Given, the eyes of the viewer are the lens(es) ‘well focused and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Design Research in Architecture

- List of Illustrations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Allegory: The Fall

- 3 The Blossoming of Perspective: An Architectural Analysis of Given

- 4 Visuality: The Act of Looking

- 5 Desire: Female Nude Drawing

- 6 Defrocked Cartesians: Duchamp's Influences and Legacy

- Bibliography

- Index