![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

Matthew Channon, Lucy McCormick and Kyriaki Noussia

Introduction

1.1 The history of car making has been one of gradually increasing levels of automation. The first cruise control was marketed in 1958. In 1995, ‘adaptive cruise control’ was launched, which allowed a vehicle to use sensors to stay a fixed distance from a vehicle in front. By 2010, more advanced functions were being added, such as ‘blind spot intervention’ and ‘active lane keeping assist’. More recently, manufacturers have begun to build on such functions to develop integrated ‘motorway assist’ systems, to take full control of the vehicle’s position and speed whilst driving along a high-speed road, under the supervision of the driver. It is then a relatively small step towards vehicles that do not require the supervision of the driver at all on certain types of roads, and from then on to full automation. It is with the law of such highly and fully automated vehicles that this book is concerned.

Development and testing of autonomous vehicles

1.2 ‘Driverless’ vehicles in one form or another have been demonstrated since the 1920s. For example, in 1926, a vehicle known as the ‘Linriccan Wonder’ was launched which could be operated by radio impulses from a second vehicle behind it. However, for many decades, as the Computer History Museum puts it, ‘real progress was more incremental than revolutionary’.1 It was not until the mid-1980s that the ‘underlying computing and other technologies needed … became available’ for meaningful development in this area.2 The increasing pace of progress can be seen in the results of the challenges set by the US Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in the mid-2000s.3 In 2004, the challenge was to design a vehicle to navigate a 142-mile desert course with a $1 million prize for the winner who managed to complete the course in less than ten hours.4 However, the technological hurdles and rugged desert course proved to be too much for the teams’ first attempt, and none finished the course – the top-scoring vehicle travelled only 7.5 miles.5 Yet by the following year, five teams finished the course.6

1.3 More recently, the testing of autonomous vehicles has become the focus of substantial commercial investment. For example, Google began testing driverless cars on the streets of the US in 2009 and had driven two million miles up to 2016. More recently, Nissan have begun testing driverless taxis in Japan.7 The UK government has so far invested millions in research and development,8 including multiple projects such as:

1.4 In 2017, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond stated that autonomous vehicles are ‘going to revolutionise our lives…and the way we work’.13 Indeed, the technology has many advocates, who cite benefits including greater mobility,14 fewer road accidents,15 environmental benefits and economic benefits. However, the road to driverless cars is not straightforward, with the safety of these vehicles, and purported benefits,16 having been called into question. The recent death of a pedestrian during Uber’s testing of an autonomous vehicle in Arizona in March 2018 has put such issues into particularly stark focus.17

Legal issues and responses

1.5 Legal issues are, of course, at the centre of some of the challenges facing this technology. The UK and a number of other jurisdictions are investigating and implementing legal reforms with a view to smoothing the path for these advances. In February 2015, the UK Department for Transport concluded a detailed review of existing legislation, culminating in the publication of ‘The Pathway to Driverless Cars: A detailed review of regulations for automated vehicle technologies’.18 In July 2015, this was followed by ‘The Pathway to Driverless Cars: A Code of Practice for testing’, designed to provide non-statutory guidelines for manufacturers and testing organisations when testing autonomous vehicles on public roads.19 This was followed the same year by the formation of the Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CCAV), a joint Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and Department for Transport (DfT) policy team. In August 2017, the CCAV introduced ‘The key principles of vehicle cyber security for connected and automated vehicles’, a set of non-statutory principles for use throughout the automotive sector.20 In March 2018, the government announced the start of a three-year project by the Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission to undertake a far-reaching review of the UK’s legal framework for road-based automated vehicles.21 Finally, in July 2018, the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 was given Royal Assent, making provision in relation to the liability of insurers where an accident is caused by an automated vehicle.22

1.6 Despite this high level of activity, it is impossible to anticipate every legal issue that will occur, as some will not become evident until more advanced forms of the technology have been introduced and are publicly available. Moreover, the breadth of the legal challenges is substantial, encompassing areas of law such as insurance, product liability, cyber security and data protection.

Technology and terminology

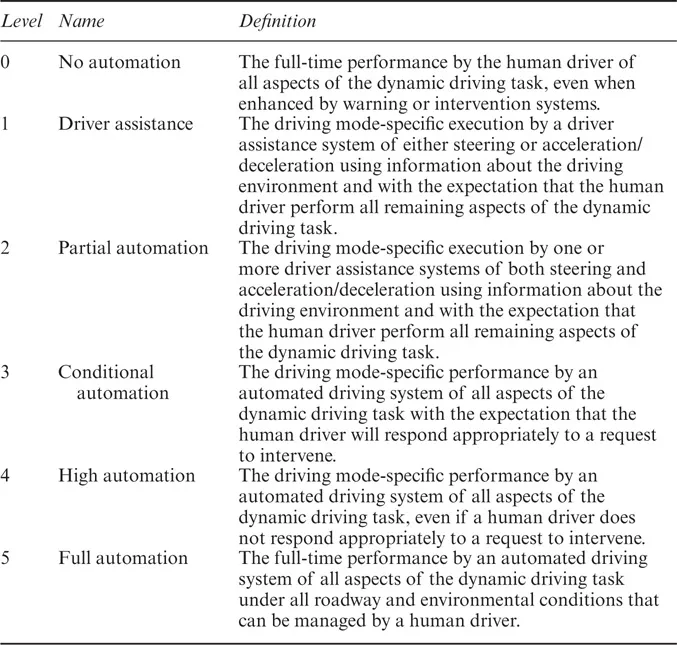

1.7 Autonomous vehicles are often described as ‘driverless cars’ or ‘self-driving cars’ –the terms are essentially interchangeable. In the industry, they tend to be known by the blanket term ‘CAV’, which is short for connected and autonomous vehicles. An understanding of the definitions used for describing the level of automation in a particular vehicle is essential in this area. A number of scales have been developed for this, almost all of which concur that ‘Level 0’ is a vehicle in which the driver is in complete control and ‘Level 5’ is a fully autonomous vehicle. The most commonly used scale is that developed by the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) and known as J3016. This has been adopted by the US Department of Transportation’s National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, amongst others. The scale can be summarised as follows:

Table 1.1 Summary of the levels of automation

1.8 The SAE levels show that the development of driverless cars is not simply a case of the vehicle having no driver, but rather a development in stages featuring both low and high levels of automation. Lower automation vehicles (up to and including Level 3) require the vehicle user to be monitoring and ‘in the loop’. This is assisted driving whereby vehicles undertake some of the functions such as parking, braking and lane assist. Later versions of assisted driving (Level 3) can perform all of the functions in certain situations, although requiring the user to be ready to take back control at any time. Vehicles with higher automation (Levels 4 and 5) will be able to drive with no assistance or monitoring. Hence, even though the term ‘driverless cars’ is commonly used, this is perhaps not conducive with the reality of their development, and where vehicles are termed ‘driverless’ it could instead connote a vehicle which has some automated features but continues to require a driver to monitor or assist.

Book structure

1.9 This book is contained in seven chapters (including the present one). Chapter 2 deals with the issue of the legal regime with regards to the testing of autonomous vehicles, in particular the 2015 Code of Practice for testing autonomous vehicles on public roads. Chapter 3 deals with the insurance law regime, particularly in light of the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018. Chapter 4 deals with product liability aspects of autonomous vehicles. Chapter 5 examines the cyber security and data protection challenges for driverless cars, and the approaches undertaken both nationally and internationally to deal with these. Chapter 6 deals with international approaches currently undertaken in relation to autonomous vehicles. Chapter 7 is a wide-ranging consideration of potential future developments in relation to the law of autonomous vehicles.

Notes

1 Computer History Museum, ‘Where to? A History of Autonomous Vehicles’ (8 May 2014), www.computerhi...