- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

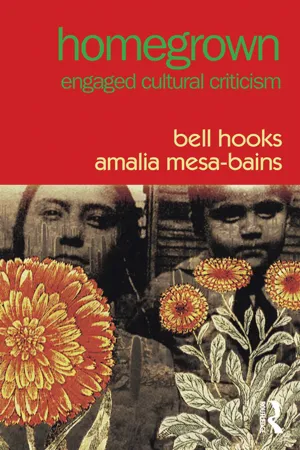

About this book

In Homegrown, cultural critics bell hooks and Amalia Mesa-Bains reflect on the innate solidarity between Black and Latino culture. Riffing on everything from home and family to multiculturalism and the mass media, hooks and Mesa-Bains invite readers to re-examine and confront the polarizing mainstream discourse about Black-Latino relationships that is too often negative in its emphasis on political splits between people of color. A work of activism through dialogue, Homegrown is a declaration of solidarity that rings true even ten years after its first publication.

This new edition includes a new afterword, in which Mesa-Bains reflects on the changes, conflicts, and criticisms of the last decade.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Homegrown by bell hooks,Amalia Mesa-Bains in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & African American Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Family

bell: My earliest childhood experiences were shaped by fundamentalist Christian beliefs. As much as anything else, they framed what girls could or could not do. For instance, on Sunday girls couldn’t wear pants, we couldn’t play music, and we couldn’t walk across the pulpit. The pulpit was considered a sacred space that a female—of any age—could not walk across, because she would defile it. In church between Sunday school and the morning service, I’d see all these boys running around and crossing the pulpit, but girls were always stopped. It was an early indoctrination into sexist thinking.

Amalia: My family life was totally shaped by Catholicism—a hybrid of Mexican and US Catholicism, as it included Irish priests from Ireland. There was this strange kind of mix of oratory and liturgy and beauty, but it was certainly fundamentalist. Catholicism belonged to the altar boys. There are altar girls now, but not then. So the fact that women maintained home altars or yard shrines posed alternatives to the conventional norm.

bell: Whereas my mother’s churchgoing was very tied with her class mobility. In fact, she wanted to get away from the Pentecostal tent meetings that working-class and poor people often attended. She wanted us to belong to a church that was modern, and for her this meant sedate, and no shouting and jumping for joy. The church only had power, but not all of it.

Amalia: Was it still Baptist?

bell: Yes, all the Black churches were Baptist, but Mama still wanted to rise in her class position, and this meant involvement in a church where there wasn’t a lot of shouting or emotional release. In our church there was one day, Communion Sunday on the first of the month, when people could give testimony and sing in the old ways. Elderly folk in the church continued to shout, but shouting was something that my mother’s generation had begun to see as unseemly.

Amalia: My mother also played a pivotal role in my Catholic upbringing. Partly because her mother took her to a Catholic convent school and enrolled her as a student, and she didn’t come back for her. The school took her in as an orphan. As a result, my mother had a very intense devotional relationship to the church, yet by the time we were born, she and my father were practicing birth control. For people of their generation and background, this was almost unheard of. And we were really different because there was only my brother and I. All of our other family members, and relatives, had five and sometimes even ten kids.

bell: Like my family—six girls and one boy! Where did you grow up?

Amalia: This was in Santa Clara, California. My dad came when he was a little boy, during the Mexican Revolution, around 1917. There were work furlough programs then, and Mexicans were going to Denver and to Pueblo, Colorado to work. My mother came across with her mom on a day pass in the 1920s to do domestic work on the American side. Both of them ended up staying here. They didn’t have papers for many years, but later they finally got them. However, this meant that for many years they lived in a very isolated way, as many undocumented people do—they were always careful to stay to themselves and not break rules. As a result, their community was tightly circumscribed, except for the church. But once my mother started practicing birth control, she couldn’t attend services anymore. So attending church became my responsibility. I was the little emissary, I would attend church and I would come back and report. I would tell everything that happened. I would save the little brochures, the church newsletter, and I would cut out the pictures in the little church newsletters of the religious images. And they were, you know, really famous religious paintings. Those were my first images of art, really.

bell: I’ve written about this. For many African American working-class people, the first art we encounter is religious iconography. In my childhood, I saw were the cheap reproductions of Leonardo, and Michelangelo…

Amalia: Caravaggio…

bell:… all of that. But I was not born into an atmosphere where art was discussed. Neither my grandparents nor my parents talked about art or the imagery we saw, which in fact was the juxtaposition of family photographs and religious iconography—prints of, you know, religious scenes.

Amalia: We had “holy cards,” and sometimes little books which depicted the lives of the saints. For me, the lives of the saints were like soap operas. They were fantastical! Lucy was blinded, with her eyes on the little plate that she carried. San Sebastian was shot through with arrows. They were really very graphic, physical, and even sexual. I think that’s why everyone loved their stories. And I always thought that the saints were like this big extended family, and through them, we seemed to be related to God, Jesus, to Mary, and all these intriguing people. These images were also part of that relationship to religion, not spirituality.

bell: That’s how I came to art, thinking about religious and family images, and then getting into the public school. I attended our little all-Black school, where art classes were offered. The good fortune of that time was that everyone took art classes. In those days, studying art was okay.

Amalia: Did you feel that you had an aptitude from the beginning, that you could draw well? Did you like to copy pictures? How did you know art was a cultural practice for you?

bell: I couldn’t draw well at all. I wanted to draw well and I took classes, worked really hard, but I didn’t have an innate gift. Among working-class Black folks, if you could draw well people encouraged you.

Amalia: That’s why I was asking about your aptitude, because that’s what some of my relatives picked up on. I’m in the third generation of artists in my family, on my father’s side. There are my great-uncles, my uncles, and in my generation there’s like five or six of us. In the generation after us, there’s even more. And I had an aptitude, I had a gift. People saw it right away, and encouraged me. My father had a brother and an uncle who were talented and made things, so he knew that I would become an artist. That’s why they supported my work, even though they didn’t think it would be a job or a way of life.

bell: My father had an elderly first cousin in Chicago, who painted dark, oil portraits of nude women. He was the first artist I knew, my cousin Schuyler—even his name was exotic. And in my teens, my parents let me go to Chicago and I saw his work. I was shocked, because it was all nudes!

Amalia: What did other people say in the family?

bell: They saw his art practice as weird. They thought the fact that he painted and saw himself as an artist was a cover for laziness. He wore a beret, and spent time alone in a basement studio dreaming and making art.

Amalia: He was a bohemian.

bell: Totally. He affirmed my interest in art, even though I did not draw well. Schuyler encouraged this passion, and so did my high school art teacher, Mr. Harrell. I’ve written a lot about my high school art teacher, because he really encouraged me. He saw me as a potential artist, and he displayed my work and awarded me prizes. My parents were opposed to this interest, because there was no money for luxuries. When I painted, I could only paint during school hours, using the school’s resources. And when I wanted to enter one of my paintings into one of the art shows, I had to have work framed to enter. My parents said, “Sorry, you can’t do this, we’re not made of money and we don’t think there’s a need for this.” I had painted this very primitive portrait of a little boy. And my parents couldn’t understand it as art. It wasn’t…

Amalia: Representational enough?

bell: The world of abstract art was just weird to them. But my art teacher helped me to gather scraps of wood, and we created a primitive frame so that my work could be in the show. I remember my picture hanging in the show, and my parents were proud of the fact that I’d won third place, but this did not mean they supported my desire to make art.

Amalia: Since making art was part of my family, they were willing to commit whatever they could afford. When I was very young, maybe seven or eight, there was a back porch on our house where the dog stayed and there was a washing machine, the kind you cranked by hand. They set up a little easel there. By then my father was no longer working in the cannery—he might have been in the grocery business. So he knew people at the store, and he would go to the meat market and get rolls of butcher paper. When he got come, he’d put rocks on the paper to flatten it out, and that became my art paper. When I went to high school, they bought me a painting set. Because it was very expensive, it was a big deal. Even then, I saw art is a kind of doorway one enters, which can lead to freedom. Sometimes people try to keep the door shut and you have to bang to get in. Sometimes people shove you through the door because they’re so sure you should go there.

Unfortunately, in high school I didn’t get along with my art teachers, because they wanted me to make work in a certain kind of way. I didn’t want to do it. I vividly remember one of my teachers marking up my image to show me how to do it correctly. I tore it up and left the class. Of course I was sent to the office for being rude to the teacher, and I kept saying, “But he was rude to me, he marked on my drawing.” No one thought I had that kind of authorship yet, so it was not mine.

bell: By comparison, my high school art teacher was an Italian immigrant. He understood what it meant to be an outsider.

Amalia: A white teacher in an all-Black school?

bell: I went to all-Black schools until I was in the ninth grade. When I went to racially integrated schools and went to art classes, there were easels. Most of the white teachers were racist, but our high school art teacher was a cosmopolitan man. He wore black, that’s one of the things I remember. Looking back I see now that he, like my cousin Schuyler, was almost like a caricature of an artist. But since he was the most cosmopolitan person I had ever encountered in my life, I associated all of that with art—freedom, independence of mind and being.

Art class was the one place in high school where I felt liberated from the drive to be the perfect Black student, always smart and uplifting my race. In art class, I could be whatever I wanted to be. He stressed that we could be whatever we wanted to be. One of his assignments was to have each of us choose an artist, study them, and try to paint in their tradition. In class, I learned about William de Kooning, and I chose to pattern my work after his. Later I learned that other Black people have had that relationship with de Kooning’s work, and I’ve tried to think about why that is the case, was it the colors that he chose, he used so many dark hues.

Amalia: Or that fact that he, like many modernists, quasi-contemporaries, really studied African art, and art from other parts of the world and really integrated them, and those gestures could be seen in their painting.

bell: Absolutely, but despite his support and interventions, my art teacher was seen as somewhat suspect. He was not a Southerner, and that set him even further apart from the other teachers. In high school, I really wanted to join this new world, and my parents told me, “Absolutely not. How will you make any money?”

Amalia: By the time I left home to go to college, my parents knew I would be an artist, but they didn’t want me to suffer, so we made a compromise. I agreed that I would study commercial art, which was very “en vogue” in the early sixties. Then when no one was looking, I switched to painting. I don’t think they realized it till I graduated. It didn’t really prepare me for any kind of living, at least in that era. It did open up this whole wide world of people who were different.

bell: Where was this, Amalia?

Amalia: San Jose State University. I went first to a junior college for a couple of years, but then I went to San Jose State. It was very wild and bohemian and there were no Mexicans, except for maybe me. At that time, 20,000 students were enrolled there, and the school had a big Greek system, with a lot of fraternities and sororities that were very, very white.

bell: Before I attended Stanford, I went to a white women’s college in the Midwest. There some of the depression I felt in my high school years, the suicidal depression set in. It was about being an outsider, and knowing I didn’t fit in there. But my parents were pleased with this college because there were a lot of rules.

Amalia: They liked the social controls.

bell: And I’d won a general scholarship. They could drive me there. It was a kind of finishing school in some ways. You didn’t have to take art classes, but if you showed an interest you could have an easel and you could paint. So I always had my own easel, and I would go to the studio to paint. Yet throughout college, all the people in that world were white men. It was the same at this women’s college. Art remained a white, hegemonic world. So I began to get into theatre, too. You’ve said that artistic endeavors—whether theatre, visual arts, or creative writing—offered space for people of color to be ourselves. In so many ways, those spaces attracted the white folk who were outsiders and who didn’t belong.

Amalia: As you’ve been talking, I’ve been thinking how I didn’t fit in with the Mexicans, either! First off, I’m from a small family, and already, people are wondering. Then, my first name is Maxine—Amalia is my middle name. Maxine? What kind of a name is that? It’s not a Mexican name. Is it the Andrews sisters? Is it Maxmilian Carlotta? What is it?

bell: What was your mother thinking, Amalia?

Amalia: She said it reminded her of a movie star’s name: “Maxine Mesa.” And in the 1930s and 1940s—I was born in 1943—Mexicans saw boxing and movie stardom as the way out. For Mexican girls like me, I called it the “Dolores Del Río phenomenon.” Years later, these images and entities are paramount in my own artwork, because they came from my mother, giving me ideas about what I would be. So “Maxine Mesa” was supposed to be a movie star.

Then, another mark against me—they didn’t pierce my ears. They didn’t want any piercing. I’ve never met a Mexican in my childhood that did not have pierced ears, except me.

bell: And wait, what was that about?

Amalia: I don’t know. No one’s ever told me. And so I had them pierced when I was eighteen.

bell: My mother and father were very opposed to piercing. We all longed to be pierced.

Amalia: Well, the first earrings Mexican girls wear are little baby crosses, as infants. In retrospect, it was very clear that somebody had already decided that I wasn’t going to be like the rest of the Mexicans. And as I got older, I feel like I located myself in a space in which I was not “Mexican,” but I could never be “white.” I know the language for it now: the interestus, or the space in between two spaces. So all of the peers that I ran around with in high school were the very popular white girls. But on the weekends and at home, my friends were Mexican kids who were related indirectly to my family through compradazco, or godparentage. They were the children that my parents helped to baptize, and they all knew me.

bell: Because I was seen as different and strange at home, I was being emotionally abused and at times whipped.

Amalia: And did your parents do that because they were afraid that if you didn’t learn to behave, things would be worse for you?

bell: Absolutely. So the only way that I could escape censure was to be talented and win their approval for something. So I became very active in acting and debate and won lots of prizes. I painted, I did theatre, I was on the debating team, and I was “booksmart” as well. And because of my mother’s class aspirations—she didn’t want to be a backwoods person like her mother—I took piano and organ lessons. I was going to be a gifted, talented, person on all fronts. I would know about appropriate manners and etiquette. I feel I was part of a wave of working-class Black people integrating the educational system in the US, and our parents were determined that we would be the best at everything.

Amalia: It’s almost like the talented tenth in a way.

bell: Something like that. The idea of “racial uplift” was certainly part of what propelled me and my neighborhood friends forward. So I always think it’s funny when folks think that contemporary feminism made me who I am. I became who I am because of my own refusal to accept patriarchy as a girl, and because I witnessed my mother’s resistance.

It’s ironic—on one hand, my mother didn’t finish high school, bore six daughters, and she dealt with many “unchosen” pregnancies, which I think are quite different from “unwanted” pregnancies. Like many women of the 1950s, she came to terms with these unchosen pregnancies and all her children became desired children. Yet she raised her girls to focus on not getting pregnant before marriage, and on getting our education. My dad said to her—and to us—that too much education made women undesirable. His message was “you’re not going to have a husband” and “yo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- preface to the new edition

- preface

- 1. family

- 2. feminist iconography

- 3. resistance pedagogies

- 4. public culture

- 5. multiculturalism

- 6. home

- 7. memory

- 8. altars

- 9. day of the dead

- afterword

- afterword to the new edition