![]()

THE CANNABIS PLANT

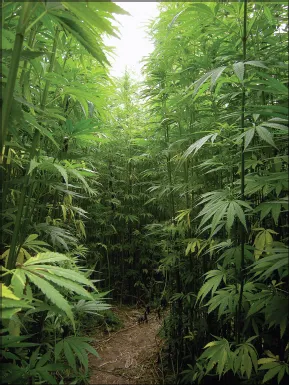

Cannabis sativa, best known as the source of marijuana, is the world’s most recognizable, notorious, and controversial plant. As befits a species that has captured the world’s attention, it is impressive in appearance (Figure 1.1). While the structure of plants may seem much simpler than that of animals, the architectural adaptations of C. sativa are very complex and are cleverly designed to carry out a wide variety of functions (Chapter 6). Cannabis plants vary enormously in height depending on environment and whether selected for stem fiber (the tallest kind), but are typically 1–5 m tall. Simmonds (1976) stated that hemp has been known to grow to 12 m in height, but it should be kept in mind that, as discussed later, other plants called “hemp” sometimes grow to such heights and are often confused with C. sativa. The main stalk is erect, furrowed (especially when large), with a somewhat woody interior, and it may be hollow in the internodes (portions of the stem between the bases of the leaf stalks). Although the stem is more or less woody, the species is frequently referred to as an herb or forb (an herbaceous flowering plant that is not grass-like, i.e., not like grasses, sedges, or rushes). Both herbs and forbs are defined as lacking significant woody tissues, so these terms are not really accurate. As discussed in this book, in many respects, deciding on appropriate terminology for cannabis is contentious.

“CANNABIS”—A COMPREHENSIVE TERM

“Cannabis” in its broad sense refers to the cannabis plant, especially its psychoactive chemicals (employed particularly as illicit and medicinal drugs), fiber products (such as textiles, plastics, and dozens of construction materials), edible seed products (now in over a hundred processed foods), and all associated considerations. In short, cannabis is a generic term referring to all aspects of the plant, especially its products and how they are used.

Biologists and editors conventionally italicize scientific names, such as Homo sapiens. Italicized, Cannabis refers to the biological name of the plant (only one species of this genus is commonly recognized, C. sativa L.). Nonitalicized, “cannabis” is a generic abstraction, widely used as a noun and adjective and commonly (often loosely) used both for cannabis plants and/or any or all of the intoxicant preparations made from them. In this book, “cannabis” is employed in its broadest sense, as explained in the previous paragraph.

THE WIDESPREAD MISUNDERSTANDING THAT MARIJUANA IS “FLOWERS” OF CANNABIS SATIVA

“Herbal marijuana” is the most frequently consumed form of cannabis, both for medical and nonmedical purposes. Herbal marijuana is obviously plant material from C. sativa, but from precisely what botanical organs does it originate? As pointed out in Chapter 12, in the past, low-grade marijuana (sometimes derisively termed “ditchweed,” although this term more narrowly refers to wild-growing low-tetrahydrocannabinol [low-THC] weedy plants) often was made up of a combination of foliage, twigs, “seeds” (technically one-seeded fruits called achenes), and material from the flowering section of the plant. Today, only “sinsemilla” (material from the flowering part of the unfertilized female plant) is commonly harvested.

Most plants have numerous flowers, and botanists employ technical terms to describe the ways that flowers are arranged on branches or branch systems. The term “inflorescence” refers to (1) a group or cluster of flowers on an ultimate branch and/or (2) the entire branching system bearing flowers. When the flowers are fertilized and develop fruits, the branching systems are termed “infructescences.” In many Cannabis strains, the ultimate branches bearing flowers have been selected to develop very congested, short branching systems bearing many flowers. These are the so-called “buds” of marijuana—desired because they are extremely rich in THC. “Buds” are technically “inflorescences”—a combination of the flowers and the ultimate small twigs of the branching system subtending the flowers. In the standard terminology of horticulture, “buds” are meristems (growing points or locations where cells divide) of stems or flowers or are embryonic stems, leaves, or flowers that will develop and enlarge with time. Like a number of other standard terms, the marijuana trade has adopted and converted the word “bud” to mean something different from its conventional meaning.

FIGURE 1.1 Cannabis sativa. Photo by Barbetorte (CC BY 3.0).

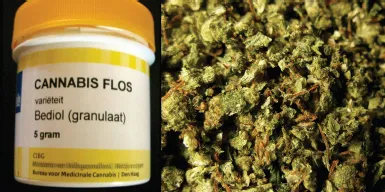

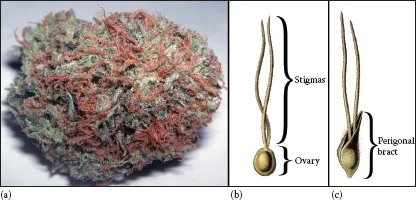

Marijuana is frequently referred to as the “flowers” of C. sativa. Indeed, in pre-Second-World-War drug literature, herbal marijuana was often known by the now largely antiquated pharmacological phrase “Cannabis Flos” (literally, Latin for “cannabis flowers”). As shown in Figure 1.2, the term is still occasionally encountered. In common language, a flower may be broadly understood to be “something that grows in a garden,” but in technical botany, a flower is usually defined as a reproductive structure composed of one or more of sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils. (This is a narrow sense botanical definition; there are broader definitions available.) Female flowers of C. sativa lack sepals and stamens and (as explained in Chapter 6) lack typical petals. A female flower, illustrated in Figure 1.3b, is virtually devoid of THC, so defining or characterizing marijuana as the flowers of the plant (which in fact are present) is technically erroneous. (Parenthetically, jurisdictions that define illicit marijuana as the flowers of the plant are subject to legal challenges, since the material so defined is harmless from an abuse potential perspective.)

FIGURE 1.2 Medical marijuana preparation entitled “Cannabis flos,” from the Netherlands firm Bedrocan, illustrating the use of this obsolescent phrase to denote material manufactured from the flowering parts of the plant. Photo by “Medische-wiet The Dutch Patient” (CC BY SA 3.0).

FIGURE 1.3 Figures presented to illustrate that marijuana is not the “flowers” of C. sativa since they are devoid of THC. (a) A “bud” of the marijuana strain Bubba Kush. Most of the visible green material is made up of tiny leaves, which are moderately rich in THC. Photo by Coaster420, released into the public domain. (b) A female flower. This is virtually devoid of THC. (c) A female flower inside a surrounding perigonal bract. The perigonal bracts contain the majority of the bud’s THC but are not visible in (a) as they are nestled deeply amidst the tiny leaves. The reddish-brown threads in (a) are dried, overmature stigmas, shown in the fresh, green stage in (b). b and c are extracted from Figure 1.5.

“Bracts” are the key component of marijuana that contributes to drug potential. Botanically, a “bract” is a modified or specialized leaf, especially one associated with flowers. The structures termed bracts in C. sativa are quite small, resembling miniature unifoliolate leaves (i.e., leaves with just one leaflet), and they are indeed associated with the flowers. As presented in Chapter 11, a “perigonal bract” (illustrated in Figure 1.3c) covers in a cup-like fashion each female flower, and enlarges somewhat, becoming densely covered with tiny secretory glands that produce the bulk of the THC that the plant produces. (The terms “bracteole” and “perigonium” are sometimes encountered as synonyms of “perigonal bract” as the phrase is applied to Cannabis but are also used in different senses when applied to other plants.) In sinsemilla marijuana, which is produced by protecting the female flowers from being pollinated, the bracts remain quite small and are very densely covered with secretory glands. By contrast, pollinated flowers develop into “seeds” (achenes) and the perigonal bract becomes much larger and the density of secretory glands is lessened considerably. In C. sativa, in addition to the tiny perigonal bracts, the flowering axis produces tiny leaves that are unifoliolate (with just one leaflet; “unifoliate,” descriptive of plants with just one leaf, is incorrect) that are scarcely different from the perigonal bracts, and as one proceeds down from the tip toward the base of the branch bearing flowers (the axis of the bud), there are increasingly larger bracts that transition into small leaves with more than one leaflet. In the bud illustrated in Figure 1.3a, the green material that is visible constitutes both perigonal bracts and tiny young leaves. The smaller tiny leaves, like the perigonal bracts, are richly covered with tiny secretory glands, while the larger leaves within the bud have a lesser density of glands and so less THC on a relative concentration basis. As explained in Chapter 13, the larger leaves within buds are often trimmed away to make the THC concentration of the buds larger. To emphasize the key point in this paragraph, strictly speaking, marijuana (sinsemilla) is not literally “flowers,” although a small amount, perhaps about 2%, is made up of female flowers virtually lacking THC; rather, it is THC-rich material (bracts, tiny leaves) associated with the flowers. The distinction made here is academic, admittedly, and is unlikely to change the widespread practice of referring to marijuana as flowering material. As pointed out by Small and Naraine (2016a), although the stigmas of the female flowers are originally devoid of THC, they are sticky, and gland heads rich in THC tend to fall away from the bud but are trapped on the stigmas, so in fact, the flowers secondarily acquire appreciable THC.

WHY CANNABIS IS CONTROVERSIAL

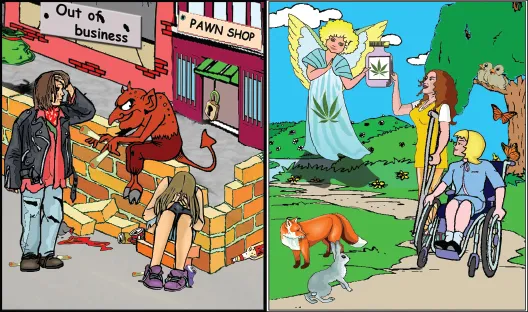

It hardly needs to be pointed out that cannabis is immensely controversial, accused of both deadly sins and marvelous virtues. It is famous (or infamous) because its chemicals have been considered to be the cause of considerable evil and harm by some, but of pleasure and cures by others (Figure 1.4). Indeed, cannabis is reminiscent of the malevolent Dr. Hyde and the saintly Mr. Jekyll—split personalities epitomizing good and evil within an individual (Small and Catling 2009). Democratic societies are currently struggling to evaluate just how bad and how good cannabis is. This book is intended to address these issues in sufficient but not overwhelming detail for the consideration of an informed public as well as decision makers.

FIGURE 1.4 The alleged good and evil sides of cannabis. Prepared by B. Brookes.

SEXUAL REPRODUCTION IN CANNABIS

We humans are preoccupied with sex, which also happens to be a subject of immense importance for cannabis. Most animals are divided into males and females (so male and female reproductive cells are produced on different individuals), although some are hermaphrodites. By contrast, most plants produce male reproductive elements (pollen) and female cells (eggs) on the same individual. Cannabis sativa is among the small minority of plants following the animal rather than the plant reproductive pattern. Most populations are divided into plants bearing only female flowers or only male flowers (Figure 1.5). Male plants are termed “staminate,” so-named because the essential male floral organs are stamens, while female plants are termed “pistillate,” so-named because the essential female fl...