- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Why is shame so central to our identity and to our culture? What is its role in stigmatizing subcultures such as the Irish, the queer or the underclass? Can shame be understood as a productive force? In this lucid and passionately argued book, Sally R. Munt explores the vicissitudes of shame across a range of texts, cultural milieux, historical locations and geographical spaces - from eighteenth-century Irish politics to Philip Pullman's His Dark Materials trilogy, from contemporary US academia to the aesthetics of Tracey Emin. She finds that the dynamics of shame are consistent across cultures and historical periods, and that patterns of shame are disturbingly long-lived. But she also reveals shame as an affective emotion, engendering attachments between bodies and between subjects - queer attachments. Above all, she celebrates the extraordinary human ability to turn shame into joy: the party after the fall. Queer Attachments is an interdisciplinary synthesis of cultural politics, emotions theory and narrative that challenges us to think about the queerly creative proclivities of shame.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Queer Attachments by Sally R. Munt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Queer Irish Sodomites: The Shameful Histories of Edmund Burke, William Smith, Theodosius Reed, The Earl of Castlehaven and Diverse Servants – Among Others

This chapter seeks to illustrate that the discursively connected histories of queerness, sodomy, shame, Catholicism, Irishness and class transgression have a pedigree stretching, at least, right back into the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The approach suggests reconstructing the structures of feeling of that era, and my inclusion of these fascinating early cases is tactical, to give us pause at the beginning of the book to consider the trenchant associations of sodomitical shame that inform our cultural politics today. Shame has been central in the making of the modern homosexual. The chapter will examine a speech by Irish politician Edmund Burke, made in the British House of Commons on 12 April 1780, on the punishment of two men, a ‘plaisteref named William Smith and a coachman named Theodosius Reed, for ‘the commission of sodomitical practices’.1 Burke would have been very cogniscent of a preceding case of sodomy, the scandal of the Lord of Castlehaven, from the previous century. This important cultural backdrop is introduced first to help us contextualise Burke’s position. Burke, in pleading for Smith and Reed to be shamed rather than murdered, effects a split between the private and public in which the future homosexual’s individuation – via the mechanism of shame – lies. Reading Burke’s speech now shows us how the category ‘sodomitical practices’ had fluctuating implications for the prospective male homosexual identity of later centuries. I chart the foetal specter of the male-identified homosexual from the early modern era, via his prism of public shame, and speculate on its unintended consequences. Hence, what Burke’s speech portends is the rhetoric of the sodomitical practice, which then solidifies into the sodomite, ultimately the homosexual, and becomes an identity (also community) formed by, within and against shame.

Edmund Burke’s measured plea for choosing pillory (rather than execution) for these men’s sodomitical crimes would have been made with his full knowledge of the ignoble history of violent retribution that the state had already enacted against those it deemed shameful offenders, such as Castlehaven. Being pilloried on the stocks was selected by the courts for its ritualised humiliation as well as torture, it was a public punishment intended to shame that has had a long history in Western societies. For example, if one visits the Palazzo della Ragione built in 1218, in Padova (Padua), Italy, today, on entering the vast hall on the first floor in the north-eastern corner one can still see the large ‘Stone of Shame’. This granite, chalice shaped figure is about one metre high, settled on a plinth, it was placed there in 1231, supposedly at St Anthony’s request. Used to punish insolvent debtors, guilty men, wearing only their underwear, had to sit on the stone three times and utter the words ‘cedo bonis’ (‘I renounce my worldly goods’). They were then banished from the city, and if they returned and were caught, they had to go through the same procedure again but this time three buckets of cold water were poured over their heads. The shape of the stone is such that it would be hard for a man’s near-naked bottom to straddle the top, he is bound to fall into the rim of the cup, and hence appear ridiculous (on the second visit – drenched and ridiculous).

Shame, suffering and banishment are close-coupled together in the Judeo-Christian traditions of social control and legal enforcement, following the urtext of Genesis. There is clearly a spatialisation operating, in the sense that traditionally the shamed persons are excreted from the social body. Pillorying enacts this by imprisoning the perpetrator’s body, removing his right of free mobility as a citizen, removing his right to isolation or seclusion, and then inciting the mob to throw excrement at him/her. The pilloried body is thus subjected to a number of spatial twists around the dichotomy of inside/outside; we are reminded that the sodomite criminal is revealed in court only to be rapidly repressed. But this social death is presumably preferable to the state-sanctioned murder of sodomites that preceded Burke’s victims, and one case in particular would have been very familiar to him.

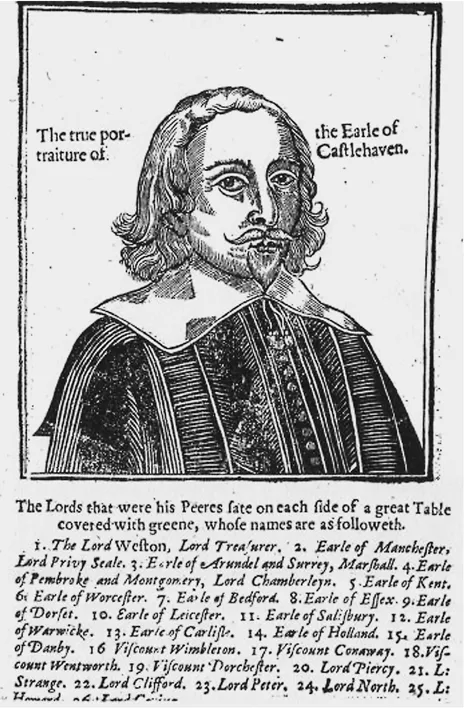

Shame, Banishment and Death: The Earl of Castlehaven

Mervin Touchet, the second Earl of Castlehaven, was executed in 1631 for abetting in the rape of his wife and committing sodomy with his male servants. Five weeks after Castlehaven’s capital punishment by beheading, his male servants Giles Broadway and Florence (sometimes ‘Lawrence’) Fitzpatrick were hanged at Tyburn. This case from early Stuart England was the most notorious sodomy case in British history until Oscar Wilde’s prosecution in 1895, 164 years later. As Cynthia B. Herrup’s excellent book A House in Gross Disorder: Sex, Law, and the 2nd Earl of Castlehaven makes clear, versions of the case have been continuously in print for almost 300 years, and it has served as a filter for debates about tyranny, redemption, marriage and the patriarchal model, homosexuality, deviance and degeneracy ever since. Mervin Touchet was a minor aristocrat who took a debauched turn, in that he is not so unusual, but his case has had intense symbolic significance for the future confluence of gender, class, and ethnicity in the cultural politics of shame.

Figure 1.1 Stone of Shame in the Palazzo della Ragione, Padua

(Photo: author)

(Photo: author)

Figure 1.2 Stone of Shame (detail), Palazzo della Ragione, Padua

(Photo: author)

(Photo: author)

Briefly, the story is that the second Earl of Castlehaven lived in the great house of Fonthill Gifford, Wiltshire, in the 1620s. As the head of a household, he was the putative father and patriarch of a powerful Norman family, the Touchets, that had recently gained lands in Ireland by the gift of James I as a result of loyal service to the King’s army. The Touchets had been landowners in Ireland since the thirteenth century. In 1612 Mervin’s grandfather George Touchet owned more than 200,000 acres in Ireland, he was a member of the Irish Privy Council, and was a member of the Irish House of Lords. He took his title from where the Spanish had landed their troops before the battle of Kinsale, Castlehaven, a small cove in County Cork. Mervin Touchet was his heir, born in 1593, he inherited a large household of staff over which he had spiritual, moral and economic authority.

Figure 1.3 Earl of Castlehaven, Contemporary Sketch

In early Stuart England there were perceived to be few worse dangers than the Irish or the Catholics, both were associated with corruption, anarchism, barbarism, and treachery. Castlehaven, through his Irish and Catholic associations, despite a public conversion to Protestantism and his rare enough visits to Ireland, remained tainted by Popery. He had openly Catholic relatives, including his brother, his father, brother, and eldest daughter who still lived in Ireland. 1730 began with Castlehaven’s brother Sir Fernando being arrested in Dover for traveling in disguise with foreign servants, the implication being that he was a risk to the Crown. Castlehaven also had Irish servants. In short, despite being a minor aristocrat, he was felt to be an outsider, as Herrup comments:

Castlehaven was a peer who stood apart from many of the conventions of the peerage: he had no ancient seat, no friends at court, no political involvement. His siblings were refractory; his subordinates dissatisfied; his spouse’s relations distrustful. He was associated with the bugbears of both Catholicism and Irishness… the accusations against Castlehaven seemed far from preposterous. (Herrup 1999, 24)2

Sodomy was at the time considered a ‘foreign’ crime, perpetrated by those uncivilised, un-English races (such as Italy, Turkey, etc.) who had escaped the noble rationality and self-control that defined the national Protestant character. It was a crime of dissemination, of lack of control, of unconstrained and lascivious desires.

The legal case was initiated by Castlehaven’s own son and heir, Lord Audley. In 1631 Audley was 17, and married – extremely unhappily – to his 15-year-old stepsister Elizabeth Brydges. They had been married by family arrangement for three years, something that in our era would perhaps be considered sexually inapt. According to Herrup ‘this couple loathed each other’ (Herrup 1999, 17). His young wife Lady Audley was having a sexual relationship with one of the servants, the Earl’s former lover, Henry Skipwith. The Countess of Castlehaven herself, Elisabeth Barnham, was 12 years older than her husband, richer, and his social superior. On 6th April Castlehaven was indicted for three felonies: two sodomies originally committed on 1st June and 10th June of the previous year with Catholic servant Florence Fitzpatrick, and the rape of the Countess allegedly committed ten days later, with the assistance of servant Giles Broadway. In court the testimony of servants and his wife contended that the household suffered from a lack of moral compass, correct governance, and failed honour. The family seat was disrupted by malice, envy, financial opportunism, favouritism, sexual voyeurism, and moral equivocation, it was ‘putrid with sexual impropriety’ (Herrup 1999, 32). The court’s view of the Earl was that he had not just failed his own household as paternal governor, but by implication breached the natural order, he was a traitor to Charles I, the King, then as now, being the symbolic head of the ‘family’ of the nation.

Sodomy was a shadowy crime: in early modern England it was difficult to ‘see’, and thus it conveniently allowed a certain plasticity of definition, and therefore proof. Sodomy and buggery, like Irishness and Catholicism, were concepts that were linked to huge fears of disorder and excess, and thus they invoked cruel and unusually violent punishments, such as that meted out later under the observation of Burke. Sodomy was seen as an act of corruption clearly marked by asymmetric class binaries, the sodomitical pairings of masters and servants, identified this crime as being particularly entangled with power and its abuse. Sodomy itself was seen ‘as an invading force; born not in English hearts, but carried to the English shores to be left as a corrosive legacy… John Marston wrote that it had entered the country with the Jesuits’ (Herrup 1999, 33-4). The 1534 Act for the Punishment for the Vice of Buggery is widely taken to be the root of anti-sodomy laws, it is best understood as part of Henry VIII’s attack on the authority of the Catholic Church, as it was aimed at priests. What is interesting about the national psychology of such fears is that it positions England, and the English, as the sodomised, it is a fear about losing corporeal integrity, and being polluted. Herrup describes how the sodomite is feared because his unrestricted appetites have no focus, they contravene all boundaries, and thus ‘Sodomy was less about desiring men than about desiring everything’ (Herrup, 1999, 33). Thus sodomitical acts were about intemperance, loss of the Protestant Godly self, a cataclysmic failure of self-governance. Necessarily, then, we might conjecture that such fears precisely underlined the ubiquity of such desires. Herrup goes on to claim that:

… sodomy was a charge more potent as an organizing principle for other fears than as a focus for solitary prosecution. Intuiting whether sodomitical acts inspired these accusations or were convenient, even disingenuous, afterthoughts to other suspicions is less important than recognizing the social utility of sodomy as an accusation… Sodomitical behaviour never appeared alone in charges against elite defendants. On occasion, sodomitical acts may have raised suspicions, but like a quark, sodomy was known primarily by its effusions. (Herrup, 1999, 37)

It is instructive to pause and consider here that Oscar Wilde was of course the only other aristocrat prosecuted for sodomy, but he, of course, was an Irishman who infamously converted to Catholicism on his deathbed.3

In ‘Can the Sodomite Speak?’ Nicholas E Radel joins the list of those looking once again at the Castlehaven case. He discusses the scapegoating of the servant, Lawrence Fitzpatrick, and understands his execution as being the outcome of his own testimony that made visible the accepted – but highly secretive – homoeroticism that circulated amongst gentlemen and servants in the Tudor and Stuart periods. Blame for this behaviour could be legitimately leveled at a servant because he could be interpreted as a minion intending to undermine the social order with his unnatural desires. Radel comments how sodomy is primarily associated with the lower born, and it is imagined to be linked to a transgression of status or hierarchy. So, what is occurring here is somewhat of a transference – the sexual traffic between masters and servants is more frequently enacted by the former onto the latter, but this would contravene belief in the master as temperate protector of his household. The blame must be transferred to the willful servant, the class manqué, linking him to an aberrant desire that threatens social stability. Radel concludes that:

Perhaps the question to raise in this context is not ‘can the sodomite speak?’ but ‘can the servant’. Class or status issues are clearly inherent in the problem of ‘voluntary’ sodomy as I have described it. One might go as far as to say that voluntary sodomy, sodomitical subjectivity, is located in the place of service, even as it reflects back onto the master. (Radel 2003, 162)

This argument was previously taken up by Jonathan Goldberg in his wonderfully titled book Sodometries in which he says ‘Accusations of sodomy in seventeenth-century New England are ways of policing emerging social and class relations’; in his analysis of William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation 1620–1647. Bradford firmly locates the sodomite as the lower class interloper (Goldberg 1992, 24). Labelling a man as a sodomite meant he lost class status, he was considered to have sunk into a filthy bestial pit, his soul irredeemably stained. Whether ‘active’ or ‘passive’ the sodomite was associated with the loss of status that was attached to femininity, the misogyny of gender hierarchy was mapped onto class. One anonymous author of an eighteenth century pamphlet Plain Reasons for the Growth of Sodomy’, quoted in Cameron McFarlane’s The Sodomite in Fiction and Satire 1660–1750 expresses that:

I am confident no Age can produce any thing so preposterous as the present Dress of those Gentlemen who call themselves pretty Fellows… –Tis a Difficulty to know a Gentleman from a Footman by their present Habits: The low-head Pump is an Emblem of their low Spirits.. the Silk Wascoat all belac’d, with a scurvy blue Coat like a Livery Frock… I blush to see ‘em Aping the Running Footmen, and poising a great Oaken Plant fitter for a Bailiff’s Follower than a Gentleman. (Anon 1730, 10–11. Quoted in McFarlane 1997, 49)

As McFarlane says ‘To slide down the scale of gender and become a “pretty Fellow” is to slide down the scale of class and become a servant rather than a master’ (McFarlane 1997, 49). Crucially, the author’s choice of verb for this sodomitical fellow is ‘to ape’, and the one recognizing and categorizing this transgression will blush. Locating aberrant, excessive, heretical or profane desires in the bodies of the working classes, (most especially the Irish and/or Catholic varieties), created a paradigm of queerness that was ineluctably related to shame.

Same-Sex Intimacy

In seventeenth-century England (and indeed in Europe more generally) expressions of passionate love between men were to be found in abundance. Ironically, the bodily expression of this love seems to have been enabled by that shadowy figure, the sodomite. Following Michel Foucault (1977a) and Alan Bray (2003), most historians of this period point to the fact that there were in fact scarcely any prosecutions for sodomy...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Series Editors’ Preface: After Shame

- Foreword by Donald L. Nathanson

- Acknowledgements

- Dedication

- The Cultural Politics of Shame: An Introduction

- Chapter 1 Queer Irish Sodomites: The Shameful Histories of Edmund Burke, William Smith, Theodosius Reed, the Earl of Castlehaven and Diverse Servants – Among Others

- Chapter 2 Shove the Queer: Irish/American Shame in New York’s Annual St Patrick’s Day Parades

- Chapter 3 Expulsion: The Queer Turn of Shame

- Chapter 4 Queering the Pitch: Contagious Acts of Shame in Organisations

- Chapter 5 Shameless in Queer Street

- Chapter 6 A Queer Undertaking: Uncanny Attachments in the HBO Television Drama Series Six Feet Under

- Chapter 7 After the Fall: Queer Heterotopias in Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials Trilogy

- Chapter 8 A Queer Feeling When I Look at You: Tracey Emin’s Aesthetics of the Self

- Bibliography

- Index