- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Selected Contents: 1. Introduction2. Theories of Institutional Dynamics3. Political and Administrative Cities4. The Evolution of Political Cities5. The Evolution of Administrative Cities6. The Evolution of the Model City Charter7. The Discovery of Adapted Cities8. Probing the Complexities of Adapted Cities9. The Conciliated City10. Conclusions

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Introduction

This book is about where most Americans live—cities. Americans have become an increasingly urban people, 80 percent of us now living in metropolitan areas with populations of more than 100,000, and 75 percent of us living in incorporated cities of 10,000 or more (U.S. Department of Commerce 1998). American cities and those of us who live in them are the subject of a vast and varied literature of which this book is just a small part, dealing as it does with three particular subjects. First, American cities are political institutions with formal structures that determine the patterns of democratic self-government practiced in each city. This book is about those structures. Second, American cities are the democratic political institutions nearest the citizens; cities are the government at hand. Americans count on cities to provide order, safety, reliability, convenience, mobility, and favorable settings for the pursuit of our economic, social, artistic, and political interests. To achieve what we expect, it is essential that our cities be both politically responsive and well managed. This book is about variations in the political organization and administrative management of American cities. Third, it is conventional wisdom that government is rigid, static, and deeply resistant to change. In virtually all respects, including how they are democratically structured and how they are organized and managed, American cities are in fact malleable, plastic, changeable, and responsive. This book is about how cities have changed and are changing.

Work on this book began in the early 1990s, generally informed by our direct observations of and experiences with local government. We engage in research and writing on American local government, and we teach those who aspire to careers in local government, particularly careers in city administration. Like others who study American cities, we presumed to understand city structures in terms of the two primary categories or types of cities—those with the mayor-council or strong-mayor form, and those with the council-manager form. Based on our observation of cities over many years, it seemed to us that, while these two forms were once useful descriptions of the political and administrative arrangement in American cities, over the past forty years mayor-council and council-manager cities are becoming less and less distinct from each other. It is our empirical observation that categorizing cities as mayor-council or council-manager had little real capacity to explain how cities were actually democratically structured, organized, and managed.

In the United States there are approximately 7,500 cities. The original structure of American city government, the mayor-council model, is essentially a separation-of-powers structure based on the design of the federal government and the state governments. Sometimes called the presidential model, the mayor-council model now includes fewer than half of all American cities. A contrasting model of local government, the council-manager model, was a significant part of Progressive Era government reforms. Council-manager cities are unity-of-powers structures modeled on business corporations. This model also resembles the parliamentary form of national government. Just over half of all American cities use the council-manager model. For reasons explained later in this chapter, we use the term “political cities” to describe mayor-council cities and their common separation-of-powers and checks-and-balances structural characteristics. We use the designation “administrative cities” to describe council-manager cities and their unity-of-powers characteristics.

The availability, in one nation-state, of 7,500 cases of democratic local government with contrasting presidential and parliamentary forms provides an extraordinary laboratory for the study of democratic institutional structures. This laboratory is greatly aided by the availability of extensive data on American cities.1 The size of this database facilitates the testing of hypotheses and the replication of findings essential to good social science. More important than the abstractions of social science, there are possible applications to other democratic governments of generalizations based on the findings of such research, applications that hold potential for improving the quality of government. With such data, one can construct generalizations about the architecture of the institutions of democracy that have explanatory power.

As part of the Progressive Era and the Reform Movement, which began late in the nineteenth century, the coming of council-manager government, or administrative cities, more than any other idea (with the possible exception of jurisdictional suburbanization) influenced the character and quality of American local government (Stillman 1974). For much of the twentieth century, the council-manager form of city government was thought to be the new idea, the reform model. As we approach the hundredth anniversary of council-manager government, it is no longer a new idea. The municipal reform movement, of which council-manager government was such an important part, is over. The rapid increase in the number of council-manager cities is also over. Council-manager government was designed to solve corruption, inefficiency, and management problems, and it did. Now that corruption, inefficiency, and poor management are no longer compelling problems, most reform cities with council-manager structures have turned their attention to issues of economic development, political responsiveness, and equity. Council-manager government, some argue, is a large and influential idea whose time has passed.

The two ordinary categories of cities are in fact legal distinctions. In the statutes of all fifty states, the residents of a particular area may, under certain rules and procedures, incorporate a city. In most states, these statutes provide for at least two city types, the mayor-council form and the council-manager form. Within these legal forms, however, city residents may adopt extensive variations. Therefore, within a particular state, two cities may be legally established as, say, mayor-council cities, yet be very different structurally. In addition, most states provide for the creation of charter cities, a legal process by which the residents of a city may custom-design the particular details of a democratic structure into a draft charter and then vote to accept or reject that charter. For the first fifty years of the twentieth century, the two statutory categories of American cities were relatively good descriptions of distinctly different structures, structures based on distinctly different kinds of democratic logic. Beginning in the 1950s, cities using both structures began a steady process of structural adaptation: the adapted cities reform was under way. But these cities continued to be legally categorized as either mayor-council or council-manager structures, categories that often masked actual structural details. Chapter 3 is a reconsideration of the reform movement from the perspective of new reform, which began in the middle of the twentieth century.

The two dominant forms of American local government, the council-manager system and the mayor-council system, are also institutional concepts. As we describe in Chapter 2, it is rightly assumed that institutions matter, that different institutions, ceteris paribus, produce different results (Weaver and Rockman 1993). Between the early years of this century and the 1950s, the structural differences between council-manager and mayor-council government were rightly judged to be important. For example, in the first half of the twentieth century, the municipal reform movement used changed structures to largely eliminate city graft and corruption. We believe that the city structural changes of the second half of the twentieth century are equally important. The purpose of this book is to describe those changes and the likely result of those changes.

In our initial approach to the subject, we thought of these two structures as clearly distinct, a bimodal distribution of structural characteristics. We used Figure 1.1 to graphically represent a bimodal distribution of political cities and administrative American cities.2 In this bimodal distribution, most political cities resting on mayor-council legal platforms exhibited relatively similar characteristics, such as directly elected mayors, mayoral veto power, partisan elections, and council members elected by party and by district, essentially the same separation-of-powers and checks-and-balances model of government one finds in the fifty American states as well as in our national government. At the time, most administrative cities had different characteristics. City council members were elected at large and without partisan references; a manager was appointed by the council on the basis of professional competence. If there was a mayor, he or she was chosen by the council, from among the council, rather than directly elected by the people; the mayor’s duties were only ceremonial.

Figure 1.1 The Structural Characteristics of American Local Government, 1910–60

Much of the study of structural change in American cities is preoccupied with overall reforms and pays little attention to incremental structural adaptations. Studies of this sort have used the two legal statutory categories of cities—mayor-council and council-manager—and assumed that these two categories captured and summarized a wide range of variation between and within each of the two types. Because replacing mayor-council government with council-manager government, or vice versa, is very rare, it would seem that there has been little change in municipal structures (Protasel 1988). Debate over the strengths and weaknesses of each model, while important, has tended to obscure a profound pattern of change that has been under way in local government. While many scholars and informed observers have been discussing the merits of political and administrative cities, in fact most jurisdictions over 50,000 in population have quietly and steadily become something different.

Beginning in the 1950s, the most prominent features of council-manager government, such as a professional executive and a merit civil service, were being widely adopted in mayor-council cities (Renner and De Santis 1998). The most prominent features of mayor-council government, such as a directly elected mayor and some council elected by districts, were being widely adopted in council-manager government. By the 1990s, the fusion of these two models had resulted in the dominant modem form of American local government, the adapted city. Almost all cities are still formally or legally labeled either mayor-council or council-manager cities, according to the state statutes under which they are organized or based on their charter from the state. But there are many details in the two categories and, as in most things, the details matter. This book focuses on the details of changes in city government because these details are the key to understanding cities as dynamic institutions.

Our research finds that the detailed features of these traditional models have been so mingled as to all but eliminate the importance of the formal designation of a city as either a mayor-council or council-manager city (Ebdon and Brucato 2000). This is not to suggest there are not some “pure” mayor-council and council-manager cities, because there are. It is to suggest, however, that there are fewer of them as time passes and that the adapted city is now the mode, especially for cities over 50,000 people. Nor do we suggest that the different values upon which mayor-council and council-manager forms of government are based are now less important. In fact, values such as professional administration, on the one hand, and democratically elected political leadership, on the other, are so important that they are no longer exclusively associated with one or the other model of local government. The emergence of the adapted city is a splendid example of the innovation, creativity, and malleability of American local government.

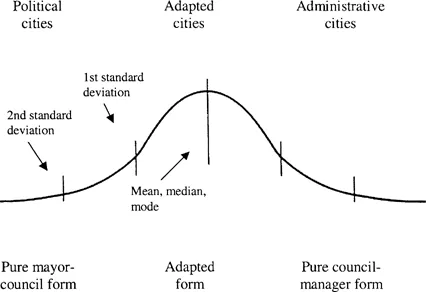

If the adapted city is increasingly the norm, how can it be best described and understood? As indicated earlier in this introduction, we initially thought to use the logic of statistical central tendency and the concept of the normal distribution. In the normal distribution, cases (cities) tend to cluster around the center, defined as the mean, median, or mode. In the normal distribution, standard deviation would indicate that 67 percent of the cases (cities) fall within plus or minus one standard deviation from the mean and 95 percent of the cases fall within 1.96 or essentially two standard deviations from the mean. Following this logic, Figure 1.2 represents the emergence of the adapted city is the modal structure of American cities.

Using the logic of the normal curve, we consider here the political, administrative, demographic, and value characteristics of adapted cities.

Change in the political details of city government in the past thirty years has been incremental. Figure 1.3 sets out our initial hypothesized assumptions regarding the direction of changes in administrative council-manager cities as indicated by the arrows. Cities with council-manager platforms are increasingly turning to directly elected mayors, usually for a full four-year term. These mayors are now more often full-time paid political leaders. As the arrows indicate, these cities have adapted from the pure logic of unity of powers in the direction of the logic of separation of powers.

Figure 1.2 The Adapted City as the Mean in a Normal Distribution

Conversely, we hypothesize that political cities on mayor-council legal platforms have not, as a general rule, changed the structural characteristics of the office of the mayor. The point is clear—administrative cities have adopted many of the political characteristics of political cities, while retaining their statutory designation as council-manager cities, becoming in fact adapted cities. In adapted cities, we argue, the dynamics of mayor-city manager relations have been profoundly changed. The manager in such a setting often becomes a partner with the mayor in matters of policy development (Nalbandian 1991). In addition, in adapted cities, the mayor is often directly involved in the day-to-day administrative affairs of the city (Svara 1989).

The structures of city council elections in administrative council-manager cities have also changed incrementally over the past thirty years. The movement has been in the direction of both larger councils and council members elected by district.

The logic of the unity of powers associated with the original administrative council-manager city has, as a result of these adaptations, been significantly altered. The city manager in an adapted city will experience a relationship with members of the city council and with the mayor that is rather different than a city manager would experience in an administrative nonadapted council-manager city. Council members elected from distri...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Tables and Figures

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Theories of Institutional Dynamics

- 3. Political and Administrative Cities

- 4. The Evolution of Political Cities

- 5. The Evolution of Administrative Cities

- 6. Model City Charters and Institutional Dynamics

- 7. Adapted Cities

- 8. Probing the Complexity of Adapted Cities

- 9. The Conciliated City

- 10. Conclusion

- References

- Index

- About the Authors

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Adapted City by H George Frederickson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.