![]()

1 | Introduction |

| M. Tavakkoli and F. M. Vargas |

CONTENTS

1.1 Asphaltene Definition

1.2 Asphaltene Deposition Problem

1.2.1 Field Cases

1.3 Objectives of the Book

1.4 Structure of the Book

References

Fossil fuels such as oil and gas satisfy a large portion of the energy demand all over the world. The U.S. Energy Information Administration (2016) predicts that the world energy consumption would grow by 56% between 2010 and 2040. Because we are running out of the easy oil, the petroleum industry faces the need to produce oil and gas in unconventional and complex conditions, deep waters, and difficult-to-access formations. One of the major challenges in this pursuit is to implement a holistic flow assurance program, that is, to guarantee the continuous and economic production and the flow of oil and gas to the refinery.

Asphaltenes constitute the heaviest fraction of the oil, which can deposit during oil production, damage the formation, and clog wellbores and production facilities. Asphaltene deposition can significantly decrease the rate of oil production. It can cause unnecessary well shut-in time and cleaning costs of up to several millions of dollars. For instance, in oil fields in the Gulf of Mexico, the average expenses associated with the asphaltene deposition problem is around US $70 million per well when well shut-in is required (González 2015). If the deposition occurs in the surface-controlled subsurface safety valve, the cost increases to US $100 million per well. Downtime losses can reach up to US $500,000 per day, based on a production of 10,000 barrel per day and oil price of US $50 per barrel. If the well is lost as a result of a severe asphaltene deposition problem, a cost around US $150 million is necessary to replace the well with a side track (González 2015).

Asphaltene has been an active research area during last few decades; however, oil companies still suffer from asphaltene deposition problems, and this has motivated both academia and the industry to actively research the asphaltene deposition problem and provide a proper solution.

1.1 ASPHALTENE DEFINITION

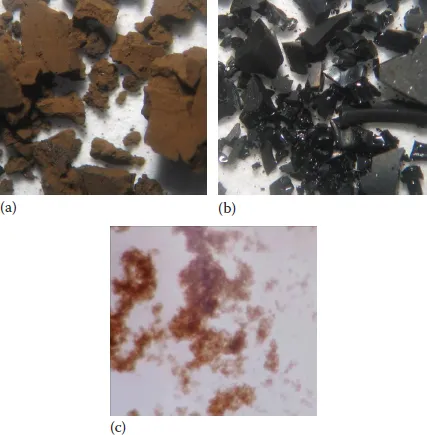

Asphaltenes are a polydisperse mixture of the heaviest and most polarizable fraction of crude oil (Tavakkoli et al. 2014). Boussingault (1837) used the term asphaltene to describe the black, alcohol-insoluble, and essence of turpentine-soluble material obtained from crude oil distillation residues. The study of asphaltenes first started in the 1930s when researchers realized that asphaltenes are widely distributed throughout the nature. Asphaltenes can be found in crude oil, Bitumen, tar-mat, and asphalts. In modern operations, asphaltenes are defined in terms of their solubility, being completely miscible in aromatic solvents, such as benzene, toluene, or xylenes, but insoluble in light paraffinic solvents, such as n-pentane or n-heptane. Depending on the normal alkane used to precipitate asphaltenes, the obtained asphaltenes have a significant difference in molecular weight, structure, and other properties. This difference is a result of the polydisperse nature of asphaltenes. Figures 1.1a and b show asphaltenes separated from the same crude oil sample using two different precipitants, that is, normal pentane and normal heptane (Buckley and Wang 2006). However, these figures show purified asphaltenes separated from an oil sample in the laboratory. During oil production, separated asphaltenes are not pure and look like a second liquid phase as shown by Figure 1.1c.

FIGURE 1.1 Purified asphaltenes separated from same crude oil sample in the laboratory using n-pentane (a) and n-heptane (b). (Reprinted from Buckley, J.S. and Wang, J.X., Personal communication, 2006.) (c) Asphaltene sample separated from a different source without any purification.

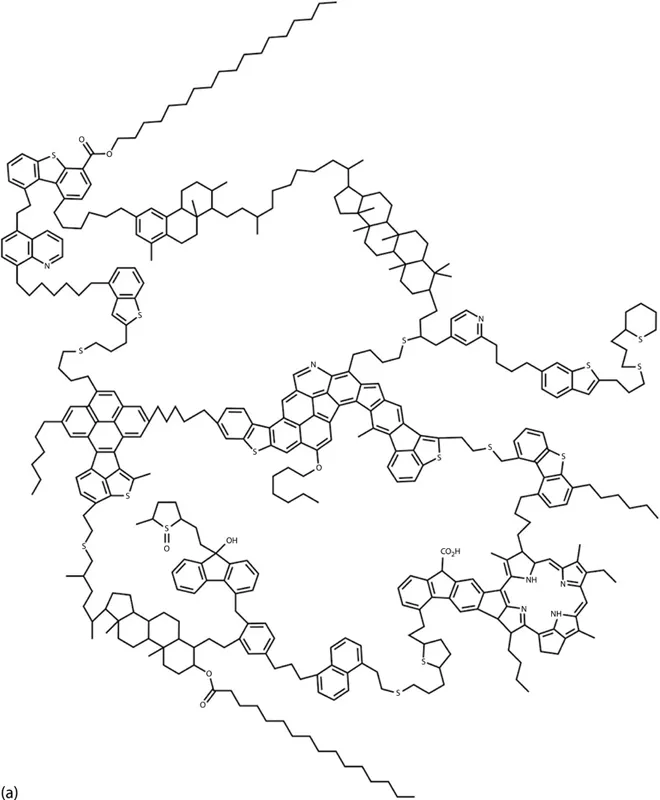

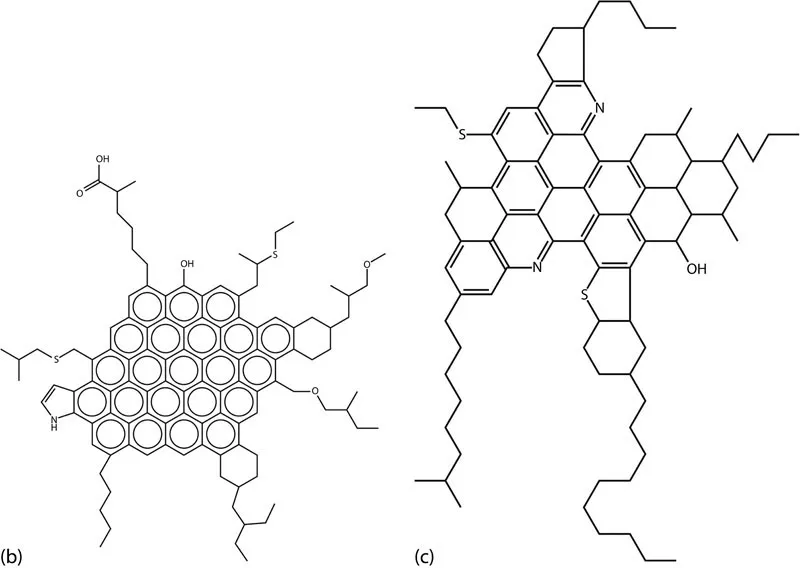

Because of the current definition of asphaltene, which is based on its solubility and not a unique chemical composition, researchers have faced many problems trying to identify this fraction of the crude oil (Vargas 2010). Despite decades of research, asphaltene chemical composition and molecular structure and their effect on the mechanisms of asphaltene stabilization are not completely understood (Vargas 2010). Chemical analyses of asphaltenes indicate that they contain fused ring structures, naphthenic rings, and some aliphatic chains that contain hydrogen and carbon; small quantities of heteroatoms, such as nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen; and trace metals, such as vanadium and nickel (Dickie et al. 1969; Mansoori 2009). Most of these heteroelements are thought to be contained in the rings because they resist oxidation. There are two main structures for an asphaltene molecule proposed in the literature: Island and Archipelago structures. Recent experimental studies using laser desorption have shown the dominance of island structures (Borton et al. 2010), consistent with other mass spectral measurements (Tang et al. 2015). Chacon et al. (2017) concluded that the more easily ionizable asphaltenes are enriched in island-type molecules and the less ionizable asphaltene fractions are likely a mixture of island and archipelago molecules. Figure 1.2 presents some of the hypothetical island and archipelago structures for an asphaltene molecule reported in the literature (Murgich et al. 1999; Rogel 2000; Speight and Moschopedis 1982).

Asphaltene molecular weight has been subject to long-standing discussions as well (Badre et al. 2006). The reason is that asphaltenes aggregate even at low concentrations in good asphaltene solvents such as toluene and form asphaltene clusters called nano-aggregates (Indo et al. 2009). It is believed that six to eight asphaltene molecules stack together and form the nano-aggregates (Indo et al. 2009). Asphaltene molecular weight measurements using the vapor pressure osmometry (VPO) and the size exclusion chromatography (SEC) have shown large values for the asphaltene molecular weight, which is most likely due to the formation of asphaltene clusters of molecules.

Measurements of molecular diffusion for asphaltenes using the time-resolved fluorescence depolarization technique have indicated that asphaltene molecules are monomeric with average molecular weight of 750 g/mol and a range of 500–1000 g/mol (Groenzin and Mullins 1999, 2000). These values for asphaltene molecular weight have been confirmed by other techniques used to measure asphaltene molecular diffusion, such as Taylor dispersion (Wargadalam et al. 2002), nuclear magnetic resonance (Freed et al. 2007), and fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (Schneider et al. 2007).

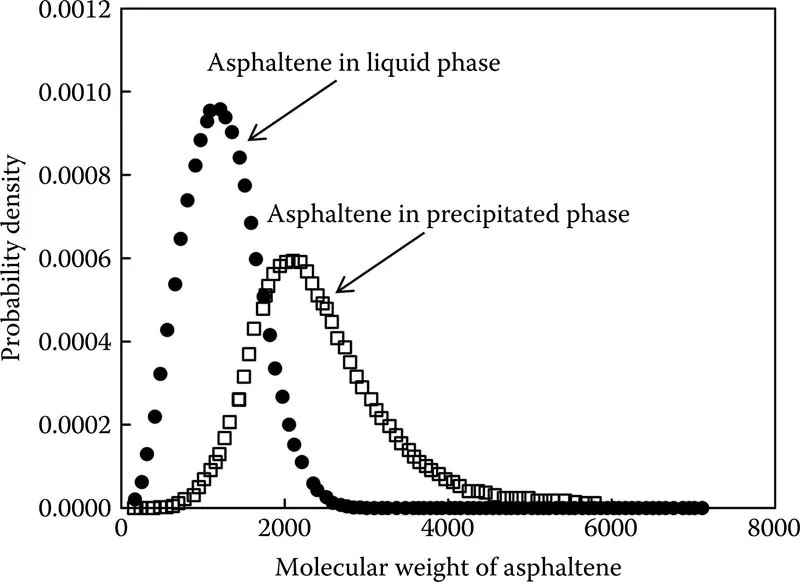

Figure 1.3 illustrates typical asphaltene molecular weight distribution for asphaltenes in the liquid phase and also for precipitated asphaltenes (Creek 2005). As can be seen, asphaltenes form larger aggregates in precipitated phase, and therefore, the peak for the distribution function shifts to the higher values of asphaltene molecular weight for the precipitated asphaltenes compared to the asphaltenes in the liquid phase.

1.2 ASPHALTENE DEPOSITION PROBLEM

Asphaltene is known as the cholesterol of petroleum because of its ability to precipitate, deposit, and as a result, interrupt the continuous production of oil from underground reservoirs (Kokal et al. 1995). Asphaltenes may precipitate out of the crude oil with changes in temperature, pressure, or composition. These precipitates may then adhere to surfaces and form deposit layers. The asphaltene deposition problem has been observed in all stages of oil production and processing, in near wellbore formations, production tubings, surface facilities, and refinery units. Figure 1.4 shows asphaltene deposition in production tubing in an oil field in the Gulf of Mexico (Yen and Squicciarini 2003).

FIGURE 1.2 Different hypothetical structures for an asphaltene molecule: (a) shows Archipelago structure. (b) and (c) show the Island structure. (Reprinted from Murgich, J. et al., Energy Fuels, 13, 278–286, 1999; Rogel, E., Energy & Fuels, 14(3), 566–574, 2000; Speight, J.G. and Moschopedis, S.E., Chemistry of Asphaltenes, American Chemical Society, Washington, DC, 1982.)

FIGURE 1.3 Typical asphaltene molecular weight distribution for asphaltenes in liquid phase and for precipitated asphaltenes. (Reprinted from Creek, J.L., Energy Fuels, 19(4), 1212–1224, 2005.)

FIGURE 1.4 Asphaltene deposition in production tubing in an oil field in the Gulf of Mexico. (Reprinted from Yen, A. and Squicciarinim, M., 225th ACS National Meeting and Exposition, New Orleans, LA, 2003.)

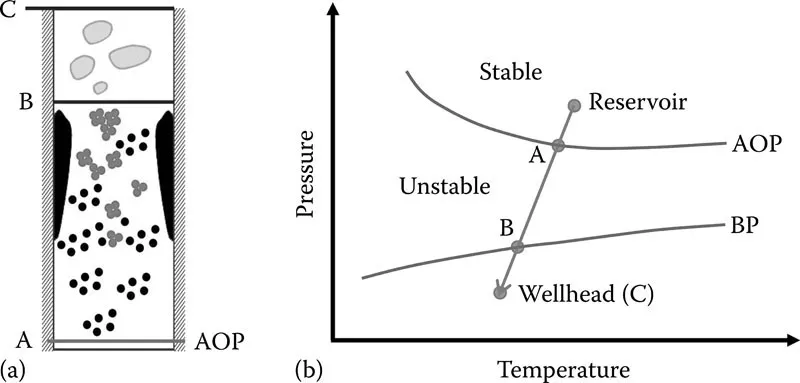

Figure 1.5 illustrates a pressure–temperature (P–T) diagram for a certain oil sample. The oil flows from the reservoir, where it is normally a one-phase liquid at high-pressure, high-temperature conditions, and enters the production tubing. The pressure and temperature start to decrease as the oil moves upward toward the surface. As the pressure decreases, the oil swells because of the expansion of light hydrocarbon fractions in the oil. Asphaltenes, which are the heaviest fraction of the oil, are insoluble in the light hydrocarbons, and therefore, the oil becomes a poor solvent for the asphaltenes when the oil light fractions expand. As a result, asphaltenes leave the oil phase, precipitate, and form a separate phase. Asphaltenes appear as a separate phase for the first time at the asphaltene onset pressure (AOP), point A in Figure 1.5. As the oil flows from point A to point B in Figure 1.5, more asphaltenes precipitate because of the more expansion of the oil light components. At point B, which is the oil bubble point (BP), light hydrocarbons start to evaporate, leaving the liquid phase. Therefore, the remaining oil becomes a better solvent for asphaltenes, and as a result, some of the asphaltenes redissolve into the oil phase. In some cases, when the oil reaches the wellhead, all the asphaltenes have been already redissolved in the oil phase and there is no sign of asphaltene precipitates. Based on this discussion, the maximum amount of asphaltene precipitation happens at the bubble point. Also, it is worth mentioning that the oil may reach its asphaltene onset pressure while it is still flowing inside the reservoir and before entering the production tubing. This mostly happens for the crude oils at their late stage of primary depletion or for the reservoirs under miscible gas injection such as carbon dioxide and nitrogen injections. These gases may get dissolved into the oil phase, make the oil a poor solvent for asphaltenes, and finally cause asphaltene precipitation and potential deposition inside the porous media.

FIGURE 1.5 (a) Schematic of asphaltene precipitation, aggregatio...