- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Design Project Management

About this book

Design Project Management is a guide to contracting and working with designers, and managing design projects proactively through to successful completion. It provides guidance for clients on simultaneously optimizing the business outcome and the creative opportunity of a design project by getting the best from a design project team through leadership, team building, mutual understanding and good communication. It also gives professional guidance to design and architecture students, and can help design consultants to ensure that they and their clients are doing everything right. Griff Boyle takes you through the whole design project from setting business objectives and design parameters, preparation of briefing documentation, shortlisting design consultants and evaluating concept design proposals and fees, to preparing forms of appointment and assembling in-house and 'external' project teams. The author explains how best to establish and meet project objectives, select works contractors and sub-contractors, and administer tenders and contracts. Advice on balancing and monitoring costs and resources, progress and financial reporting, and change control mechanisms is also given. To highlight typical problems and their solutions the author quotes case study examples from interiors, exhibition, refurbishment and multidisciplinary projects. Public and private sector managers involved in building services, retail, leisure, exhibition and office schemes will find this book saves them time and money, whether or not they have an in-house design team.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The key to design management

INTRODUCTION

This book about design project management has been written primarily for client organisations who may work with designers regularly, or who may have been asked to work with designers for a one-off project while carrying out their own ‘core’ non-design business duties. It has not been written primarily for designers, although designers may also find it helpful. It sets out to explain and demystify the design process for the non-designer, making analogies wherever possible with more familiar everyday business experiences and processes, illustrating a step-by-step methodology for integrating design into a business. It is a client's guide to initiating, setting up, directing and managing successful design projects. Examples are drawn mainly from multidisciplinary projects for the built environment, but the approach and principles described are applicable to other design projects.

Underlying the book is the desire to promote clarity, communication and integration of effort between all parties engaged on a design project. At its heart is the belief that these factors will make possible a match between the end result expected from the project and the end result achieved. Thus all contributors must share the same set of aspirations and expectations simultaneously. While recognition of the need for clarity has motivated this book, the core significance of shared design project values optimises the creative and business potential of the project.

If a designer is asked to identify the most important factors contributing to a successful design project, the following will probably appear repeatedly among the top four answers suggested:

• A good budget

• A good brief

• A good client

• An appropriate timescale.

While there may be some disagreement regarding the exact order of priority, there is likely to be little debate about the ability of each factor to influence a design project either for good or ill. However, the factors noted above fall into two distinct categories. On the one hand, there are ‘hard factors’ – finance and programme. These are usually easily objectified and determined through a business imperative. On the other hand there are ‘soft factors’ – a ‘good’ client and a ‘good’ brief. These are far less easy to establish or agree in objective terms, and whose perspective should be used?

Beginning a book professing to be a client's guide to successful design project management therefore demands that we start with establishing some fundamental definitions regarding design, design projects, success, good clients, good design briefs and so on.

• What do we mean by design?

• What do we mean by design project management?

• Who judges what we mean by success? Can the success be measured?

• What makes a good client? Brief? Budget? Programme?

Each of these questions is considered as the book sets out a first-principles sequential map of the areas of concern that are always present in any design project. It aims to provide clients from any area of business with the tools necessary to understand designers and the design process. It provides checklists for each major stage in the evolution of a design project, and brief case studies to illustrate points of principle. The book seeks simultaneously to recognise the unique nature of individual design projects and strongly emphasise the common patterns underlying each.

If after reading this book only one piece of information is to be retained by the reader it should be this:

The key to successful design rests with the client, not with designers.

WHAT DO WE MEAN BY DESIGN?

For the purposes of this book successful design is not viewed from the perspective of creating purely personal statements, such as those that arise, say, from the completion of domestic-scale interior design projects. Here the outcome of the design may be viewed by one party to be a success with no visible, objective criteria to enable others to form an assessment; that is, there is often no right or wrong view, other than a response based on personal taste. This book views design from a broader perspective, considering how it may best be integrated into the wider spectrum of meeting the business needs of an organisation, where success may be assessed and indeed measured through strict business criteria. It is important to establish such key factors for a book such as this, as it should be possible to measure the success of the book by judging its usefulness to the reader against the criteria established.

Design, defined in its broadest sense, is an activity we all undertake many times every day. In getting on with daily life, we all design and redesign processes and activities to fulfil our own needs, from children crossing roads to business people evaluating complex strategic business processes. Design is an activity that goes well beyond a concern with form and surface and the purely visual criteria with which it is often most readily associated by the public, and too often by designers themselves. Design is the activity of turning a ‘need’ into a solution, a ‘concept’ into a reality. The solution may have or may not have a physical form, but it will certainly have a purpose, and the emphasis in this book is on design purpose, and more specifically the holistic ‘fitness for purpose’ achievable through integrating design properly into a host business.

A visually led approach to evaluating design often attempts to position it as an activity to which the untrained are unlikely to be in a position to contribute, or perhaps even understand – an activity closely aligned to having ‘talent at art’ or ‘good taste’. This is a position sometimes unfortunately reinforced by designers themselves through the production of drawings and the use of language which does not adequately communicate to the layman – a position often driven by criteria amounting to little more than self-satisfaction, and the wish to express values considered important by peers.

The position of design as ‘elitist activity’ is one that this book sets out to demystify, passing an understanding of the design process back to the end user. This will generate a position from which clients may communicate meaningfully with designers, evaluating their abilities and values, and integrating their vital and valuable professional services into the business of the host organisation.

In their 1997 Contribution of Design to the UK Economy report the Design Council recognised the struggle by previous authors and researchers to define design not in terms of profession or specialism but as a socio-economic activity.1 It identified the following basic approaches:

• Economic/technical: arising from a perspective that attempts to quantify design activity in economic or technical terms.

• Philosophical: arising from a perspective which suggests that design cannot be quantified.

• A synthesis of these two standpoints.

The approach to design taken in this book is a synthesis of the ‘economic/technical’ and ‘philosophical’ approaches. Finding the correct balance of these factors on any project determines how successful the outcome will be.

Design often requires resolution of seemingly contradictory thought processes: creativity and logic; innovation and pragmatism; intuition and analysis; listening and talking; problem identification and problem solving; progress and control; technical and strategic thought. It involves reconciliation of aesthetic and sensory qualities with legal and statutory implications.

To articulate intention during the design process requires a range of communication skills – visual awareness, three-dimensional thinking, drawing abilities, verbal communication.

Design must simultaneously add value to a business, express visually its own unique purpose and qualities, and function successfully.

THE DESIGN PROCESS

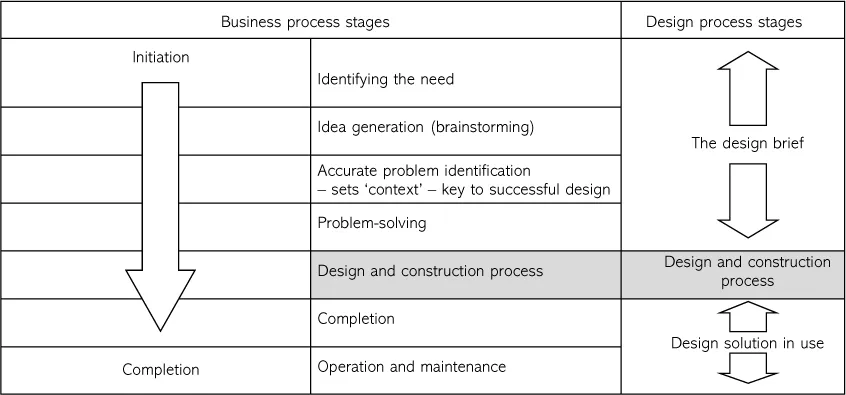

The design process is not purely linear, but a simplified overview may be described in a linear fashion as shown in Figure 1.1 to permit further discussion of iterative aspects of the process.

Figure 1.1 The design process from a client organisation's point of view: ‘design’ is one small part of an overall process

Figure 1.1 outlines the design process in its broadest sense and can be applied to all design disciplines. A business or other need is identified, following which ideas will be proposed for meeting that need. A single idea will be selected from the list of potential ideas and this will be developed to completion and use. The importance of this early stage and its ability to influence all later stages in a positive or negative manner is obvious. It will also be recognised that it applies generically to most forms of business process and indeed other everyday basic human activity. Although the levels of complexity and speed of ‘life cycle’ are different in each, crossing a busy road and business planning have much in common as processes, each requiring an appropriate ‘design’ to suit the identified objective in response to external conditions, and each requiring progress and control with constant evaluation and re-evaluation of earlier decisions.

The importance of the client to the success of the overall design process should be apparent from Figure 1.1. The design brief establishes the context of the future actions of all contributors to a design project. While the brief will contain problem-solving guidance relative to the need for the project, the key aspect is the problem identification stage. In design, as with many things in life, the correct answer will only ever emerge in response to the correct question.

While individual projects have a defined timescale, the design process is an iterative process which never truly stops. The reasons for this iteration may be driven by the search for a response to changes from either internal or external influences and constraints. For example, improvements to a design may become apparent in use, from observations regarding materials, function, ergonomics, economics of manufacture and so on, and may represent incremental improvements in the operation and maintenance of a design, the point here being that ‘the need’, and hence the bri...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- 1 The key to design management

- 2 Assembly of the client team

- 3 The briefing process

- 4 Shortlisting design consultants

- 5 Presentation of concepts and assessment of proposals

- 6 Appointment of design consultants

- 7 Design development, design coordination and information management

- 8 Tendering and contract strategy for works contractors

- 9 Project management

- 10 Post-project review activity

- Bibliography

- Further information

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Design Project Management by Griff Boyle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.