eBook - ePub

The Greening of Architecture

A Critical History and Survey of Contemporary Sustainable Architecture and Urban Design

- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Greening of Architecture

A Critical History and Survey of Contemporary Sustainable Architecture and Urban Design

About this book

Contemporary architecture, and the culture it reflects dependent as it is on fossil fuels, has contributed to the cause and necessity of a burgeoning green process that emerged over the past half century. This text is the first to offer a comprehensive critical history and analysis of the greening of architecture through accumulative reduction of negative environmental effects caused by buildings, urban designs and settlements. Describing the progressive development of green architecture from 1960 to 2010, it illustrates how it is ever evolving and ameliorated through alterations in form, technology, materials and use and it examines different places worldwide that represent a diversity of cultural and climatic contexts. The book is divided into seven chapters: with an overview of the environmental issues and the nature of green architecture in response to them, followed by an historic perspective of the pioneering evolution of green technology and architectural integration over the past five decades, and finally, providing the intransigent and culturally pervasive current examples within a wide range of geographic territories. The greening of architecture is seen as an evolutionary process that is informed by significant world events, climate change, environmental theories, movements in architecture, technological innovations, and seminal works in architecture and planning throughout each decade over the past fifty years. This time period is bounded on one end by the awareness of environmental problems beginning in the 1960's, the influential texts by Rachel Carson, E.F. Schumacher, Buckminster Fuller and Steward Brand, and the impact of the OPEC Oil Embargo of 1973, and on the other end the pervasiveness of the necessary greening of architecture that includes, systemic reforms in architectural and urban design, land use planning, transportation, agriculture, and energy production found in the 2000's. The greening process moves from remediation to holistic models of architecture. Geographical landscapes give a global account of the greening process where some examples are parallel and sympathetic, and others are in clear contrast to one another with very individuated approaches. Certain events, like the Rio Summit in 1992 and Kyoto Protocol in 1997, and themes, such as the Hannover Principles in 2000, provide a dynamic ideological critique as well as a formal and technical discussion of the embodied and accumulative content of greening principles in architecture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Greening of Architecture by Phillip James Tabb,A. Senem Deviren in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Architecture & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Origins of Green Architecture

As from a seed the tree grows, so from a seed idea a pattern issues forth from the Center, passed on by ranks of silent angels—silent and still because that idea is too unformed and unfixed to endure any but the most exacting care.1

INTRODUCTION

Modern architecture, and the contemporary culture it reflected, contributed to the cause and necessity of a burgeoning green process that has emerged over the past half-century. Modern architecture broke from the eclectic traditions of the 18th century and focused on abstraction, standardization and serial production seeking a homogeneous international identity. As the world evolved with greater complexity and increased reliance upon technology, it was exhilarating and bewildering—and to a large extent was energy inefficient. As a result, it added unintended adverse consequences to the environment and exposed our dependence on fossil fuels. Beginning in the 1960s, works of Rachel Carson, E.F. Schumacher, Buckminster Fuller, Ian McHarg, and Stewart Brand, focused on the harmful effects to the environment and the awareness of holistic environmental thinking. Fortunately, earlier climate responsive architectural works by Le Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Ralph Erskine, Constantinos Doxiadis, Louis i. Kahn and Alvar Aalto, emerged as early modernist green precedents. The ever-closing circle of a single set of modernist universal principles was reconsidered by place-oriented intentions that initiated a diversity of environmentally conscious designs.

The Greening of architecture became an emerging process that attempted to transform modern architecture into more benign, environmentally oriented buildings. Green architecture evolved into a practice that advanced initially from rationalist, performance- based and remediating measures in response to particular unsustainable concerns, to far more encompassing ecological and systemic processes cutting deep across contemporary culture. So pervasive was the greening of architecture that, according to Julien de Smedt (JDS Architects), there was a definition problem. “‘Green’ and ‘Sustainability,’ the terms used to name the answer to the most pressing problem of our time, have become dangerously afloat in ambiguity and indeterminacy. Sustainable architecture is everywhere and nowhere.”2 Nevertheless, the green movement grew as a global phenomenon seeking an accumulative reduction in the negative environmental effects caused by buildings, urban designs, settlements and other public works. Simultaneously, it served to explore environmentally oriented canons with new tectonic and emergent architectural languages.

The need for sustainable planning and design was not a new design consideration or determinant. Certain constructions for shelter, protection, and the need to create tolerable levels of comfort were considered in ancient designs and not surprisingly, still remain important today. The very term “shelter,” meaning to provide cover, derives from the need for physical safety, to mitigate the negative effects of weather and adverse conditions of the environment, and to provide a place of dwelling. Over the centuries, various cultures developed specific architecture and planning responses to differing climatic conditions. These responses were refined progressively over time, usually from the development of single vernacular dwellings to larger urban settings. The English village, for example, grew from the rural cottage to the agglomeration of cottages into more compact settlement forms, especially during Celtic and Anglo-Saxon times (500 BC–1066 AD).3 There were many lessons to be learned from the past’s coping with climate and growing societal complexities that together with new green architectural technologies, could provide appropriate and intelligent approaches for future current and use.

The reaction to the harmful consequences of the Modern Movement—wasteful use of land and resources, inefficient and unhealthy construction practices, over-dependence upon fossil fuel-driven technologies, and reliance on the automobile for transportation to name a few—is warranted, but not entirely without a truly acceptable alternative. Yet, there seems to be an inextricable bond that still remains between modernism and the greening of architecture, which is amplified with the newest of examples in green building. This contradiction in philosophy, principles and perception of need has led to confusing and ambiguous results, which this chapter addresses. It is important to see the greening of architecture as an evolutionary process and cyclical ecology rather than simply a fixed set of strategies for a fixed period of time. A more dynamic and iterative view allows for the natural shifting of cultural values and needs to ever-increasing levels of sustainability, which in turn fosters a maturing architectural and urban response. It is a process that can affect every facet of contemporary culture toward attaining a more sustainable future. Sustainability goes far beyond the buildings and cities to include nations, continents and the planet as a whole.

EARLY GREEN DESIGN STRATEGIES

Early examples of green architecture were by necessity climate responsive, providing shelter from inclement weather, and they also responded to other environmental concerns, such as on-site water collection, sewage removal and fuel for heating. Butti and Perlin suggested that the ancient Greeks had no artificial means of heating or cooling their homes. In winter they used mostly portable charcoal-burning braziers along with warmth they could glean from the sun during the day. However, as populated areas began to expand, surrounding forests were ravaged for wood for heating and cooking. By the 5th century BC many parts of Greece were almost totally denuded of trees.4 Knowledge of seasonal changing of sun angles precipitated more aggressive vernacular designs that allowed the lower winter sun within the dwelling for warmth and the higher summer sun excluded to help mitigate overheating. The northern façades, with few or no windows at all, were constructed of thick masonry walls to keep out the cold winds in winter. These ingenious design measures crossed class lines from temple or palace to commoner’s dwelling, which resulted in a cultural proliferating effect.

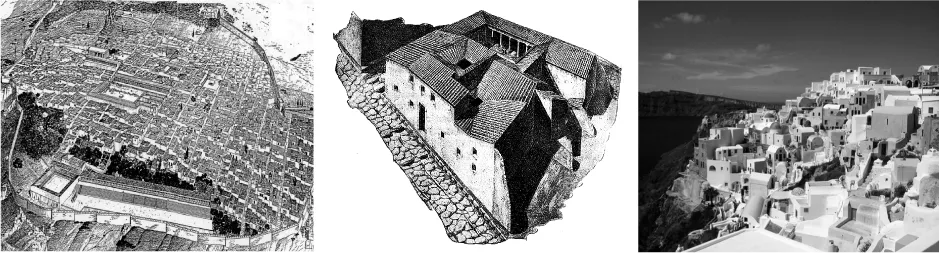

The Olynthian house, for example, was typically organized around a south-facing exterior portico and court that served as a private outdoor room and provided light and solar heat to the adjacent indoor spaces. The portico and roof eaves served to shade the sun in summer. The house designed with an integrated courtyard was the general scheme. The entrance to the dwelling was from the street and led directly to the courtyard. Surrounding the courtyard were all the other rooms, which opened into it. A portico with colonnade was built on the north side of the courtyard, which faced south for maximum sunlight. At ground level was a living room with a central hearth surrounded by a kitchen and bathroom. A men’s room was fitted with typically seven couches around the perimeter for dining. The remaining rooms on the ground floor were for storage. The women’s quarters and bedrooms were built above the northern half of the house. Slaves and family lived together as one big family. The significance of this work was in both the development of single building sustainable strategies in conjunction with urban design schemes, which provided the context for a compact sun-oriented settlement plan. Figures 1.1 a and b illustrate the predominant cardinal grid pattern for Priene and a reconstructive drawing of a typical early Roman urban residence with interior court.

1.1 Ancient Green Predecessors a) Priene reconstruction image (image courtesy of the German Archaeological institute) b) Drawing for early roman Domus (image courtesy of the Vroma Project (www.vroma.org)) c) Oia, Santorini Today

Modern excavations of many Classical Greek cities reveal the principles that generated these effective vernacular designs, which carried over into urban planning where street widths and orientations considered this solar phenomenon giving equal access to the sun for all structures. The Ionian city of Priene (1000 BC), located on the southwestern coast of Turkey, was a good example of urban design for challenging topography and excellent solar access. The region of between 4,000 and 5,000 residents was relocated because its original site was plagued with constant flooding, and therefore Priene was planned on higher ground beneath the escarpment of Mount Mycale. The six main avenues were placed on terraces paralleling contours and running east and west including the central avenue that was fed by the main west gate entrance. The avenues were wider providing solar access to south-facing building façades. Secondary streets ran up the north–south slopes and tended to be narrower. The agora occupied the center of the plan was situated on a widened contour to accommodate the larger open space. The city was divided into four districts—political (Bouleterion), cultural (Theater), commercial (Agora), and religious (Temple of Athena). According to city planner Edmund Bacon, “the most remarkable thing about Priene is the total harmony of architecture and planning, extending from the over-all form of the city down to the last detail.”5 The photograph of Oia, Santorini in Figure 1.1 c shows the earth sheltered solar-oriented residential forms cascading along the island’s interior. These same principles were practiced in ancient China with important streets aligned along cardinal directions and the design for solar-oriented houses. In other climate zones and geographic locations, architectural and planning measures have responded to climatic conditions. For example, the powerful image of the city of Hyderabad, Pakistan demonstrates the pervasive use of hundreds of wind catchers used in many Persian cities as seen in Figure 1.2a. These examples are a good illustration of multiplicity of form, land-based design, and the Generative Principle.

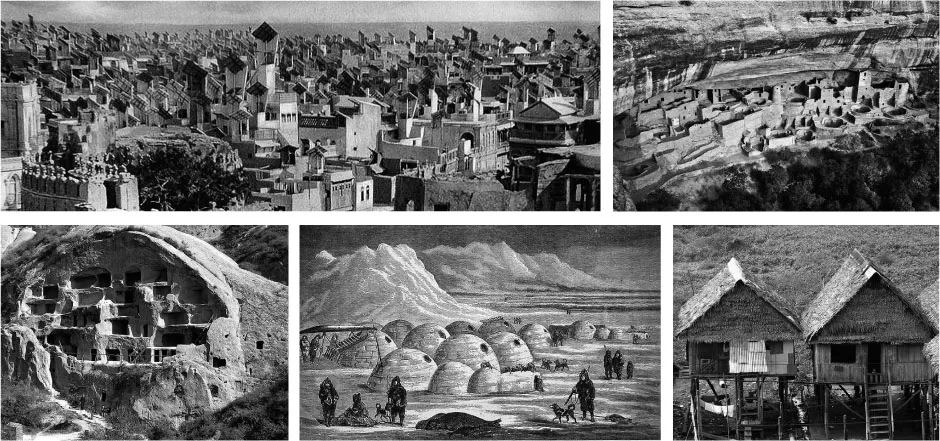

1.2 Climate Responsive Examples a) Hyderabad, Pakistan Wind-catchers (Mangh) (1928) b) Mesa Verde, Colorado (image courtesy “Shutterstock”) c) Yanqing Guyaju, China d) oopungnewing Village (1865) e) Stilt House of Myanmar

Certainly, climate-responsive architecture and planning were not only confined to Ancient Greece and Asia Minor. Other locations worldwide indicated architectural designs for varying climate zones, extreme weather and natural hazards, and according to architectural historian Paul Oliver, these buildings did not “control” climate, but rather “modified” climate by affecting internal conditions toward greater levels of acceptable comfort.6 Oliver suggested that, “arguments have been powerfully made for a physical and environmental determinism that considers that advantageous climates and temperatures, soils and seasons give shape to man’s culture.” These examples cross both time and geography representing varied design responses to differing environmental conditions. For example, the Swiss alpine house, the English cottage, the igloo of the Inuit, raised platform dwellings of the Amazon Basin, the adobe dwellings in southwest North America, the underground dwellings in China, and the wind towers of Pakistan, all have formal characteristics unique to the environments within which they respond. The Long House at Mesa Verde, Colorado, shown in figure 1.2b, utilized the concave rock formation for the advantage of solar energy exposure in winter and solar shading in summer. Typical, among the climatic design strategies were direct form and material responses to the prevailing climatic and environmental conditions, such as, the use of insulating and heat retaining materials and solar energy in colder climates or use of stilts, raised platforms for flood-prone tropical areas, and extended roofs for capturing breezes and for solar shading.

Roman architect, Marcus Vitruvius, in the 1st century BC, developed a set of architectural principles, known today as The Ten Books on Architecture,7 which included planning and design guides and patterns on different aspects of building. In Book Vi, Vitruvius described the importance of climate in siting and design, recognizing that different climates required different design approaches. He also addressed the proper exposure of different rooms to qualities of light and exposure to the sun for warmth. In Book Viii he described the finding of water, its differing qualities, collecting and exporting it and uses for it—showering, drinking and cooking. He felt that rainwater was wholesome and that the vaporous properties of different waters should be considered. He describes the many innovations made in building design to improve the living conditions of the inhabitants. Foremost among them was the development of the hypocaust; a type of central heating where hot air generated by a fire was channeled under the floor and inside the walls of public baths and villas. Vitruvius also recommended that in hot climates the north facades should be open away from the sun. In A Green Vitruvius, J. Owen Lewis suggested that the sustainable principles put forward by Vitruvius could be distilled into relevant design patterns, which are applicable today.8

The shelter with protective roof, thick walls and openings became the archetype for refuge and early climatic designs. The roof provided protection directly above from rain, sleet, snow, winds and the high hot sun in summer, and was also a symbolic element mediating between heaven and earth. Heat naturally rises, so roofs in cold climates tended to be lighter with higher insulation values for containing it. Thatch,...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- 1 Origins of Green Architecture

- 2 1960s: An Environmental Awakening

- 3 1970s: Solar Architecture

- 4 1980s: Postmodern Green

- 5 1990s: Eco-Technology

- 6 2000s: Sustainable Pluralism

- 7 The Global Landscape of Green Architecture

- 8 Conclusion

- Index