![]()

1 Work overview and philosophy

Rosemary Raddon

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

(W.B. Yeats (1919), ‘The Second Coming’, in Collected Poems, London, Macmillan, 1950, pp. 210-11). (By permission of A.P. Watt on behalf of Michael B. Yeats)

CONTEXT

Careers and lives are usually rooted in some way in the world of work, and this changing phenomenon of work forms the outer layer of a complex system. Work is one of the main external drivers in an intricate system containing a range of smaller systems, subsystems, relationships, possibilities and personal responses to all of these. All interact with each other and are interrelated. At the centre is the individual psyche, with its own specific history, experiences and responses.

The changes in the drivers, form, content and structure of work have been evolving since the first exchange of goods and labour existed, but within the last century the pace of this evolution has accelerated, and information and the information professions have been among some of the most rapidly changing areas. These changes have been taking place in a context of social, economic and technological flux, linked to realignment of political ideologies. Globally these changes have included a rapid increase in competition, cross-border networks, the reduction of fixed places and systems in relation to finance, to systems which are now connected through technology, shifts in political interventions and the decay of some larger states and the rise of others. All these in turn link to alterations in the places where goods are produced, with some areas of the world decreasing in power, and others becoming increasingly important as sources of cheap labour and expertise, thus altering global relationships. Migrations and work patterns have also changed. Work and technological changes have then occurred as a result of these shifts, bringing alterations in linked social structures. Societal changes have also been part of these shifts, and organizations in turn have changed to reflect the changing global pattern.

Organizations have responded through the increasing use of technologies, changing formal structures, decentralization, improved flexibility, structural alterations in the workforce, and different responses to issues of race and gender. There is more stress on partnerships and the importance of stakeholders, and more flexibility and lateral thinking. Portfolio working is no longer innovative and new, and careers are not hierarchical and rigid. At the same time the gap between some countries and trading communities and others is widening. Political and religious movements are contributing to this gap, and tensions arise between traditional capitalist issues and values, and those of increasingly articulate alternative movements. All are supported and fuelled by global information systems and technological infrastructures. These support or may drive service or manufacturing economies or systems. These systems have and are in turn affecting economic, social and political movements. A survey of the national press of the United Kingdom of the last year will yield endless examples of these symbiotic processes. All contribute to the ever-changing and increasingly rapidly changing world of work.

The information professional, like other technological professionals, is an integral part of these changes, responds to them in a variety of personal and professional ways, and cannot be isolated from them. Perception of work and career satisfaction takes place within this broader picture of the so-called information society and of information technologies. Change and changing values, differing impacts, changing and diverse patterns of work and organizational shifts have to be managed and utilized, in relation to individual needs and aspirations. These individual needs and aspirations have to be seen within the wider context or system, but also within the context of a particular situation, organization or country. There has to be an analysis of the individual situation and of the particular structural framework. Such an analysis prevents individual needs and expectations being acted out or phantasized about within a seductive and over-simplified organizational or global framework. Managing self and the individual career requires such an overview in addition to the ability to focus on the specific.

THE WORLD OF WORK

Work is an integral part of most of our lives, experienced in many ways. The range of these experiences is rich and varied, and the words and phrases used to describe work and the emotions attached to it indicate that range. Students and workers use descriptors such as responsibility, realization, fulfilment, discipline, ideology, commitment, hurt, anger, pleasure, unemployment, fear, rejection, slavery, love, transformation, harassment, money, creation, family, alienation, defence, economics, bureaucracy, development, offensives, confidence, control, and many others. These free association descriptors indicate some of the experiences of work, expressed in external reality and in the ways in which work brings deep feelings to the surface. It can be seen that work can be experienced as day-to-day reality in a variety of ways, which may range from pleasure and rich rewards to boredom, pain, rejection and possibly unemployment. It can also be experienced as a phantasy (the perfect job/manager/organization existing somewhere at the end of the rainbow) of personal or other aspiration, as the fulfilling of ambition (real or imagined), or as compulsion, arising from internal unconscious drives or undertaken to satisfy the ambitions of another. It may be experienced as an alternative fulfilment for other unfulfilled needs, as an antidote to failure in other areas of life, as a result of social or peer pressure or relationship issues. It may also be experienced as the source of sophisticated material pleasure, kudos or esteem, or as the opposite – the ultimate yet unobtainable goal and the source of endless rejections.

So work can be experienced at many levels. Some of these levels are clear and often universal. Most of us have to work to survive economically – the reality of having to deal with the economics of living are observable and part of a complex social system. Decisions on work, families, location, levels of spending, loyalties, choices within or outside the system, are made and informed to a large extent by work. In addition to these concrete observable choices, other choices are made at a more unconscious level. Work gives many of us a role, an identity, a framework and the ability to operate within an acknowledged social system. Either overtly or covertly, many people perceive work as some kind of contribution to their society or environment. It makes some contribution to the eternal question ‘what is it all about?’ and provides a contextual process which provides a framework for an activity which occupies major elements of time. The degree to which these choices, and therefore needs, are met by the world of work depends on the degree of sophistication of the understanding of our own internal make up, and how this affects our working lives. Work is to some extent also determined by gender, and the social and political constructs which are built around this. Career choice is also affected by gender to some extent, and may be considered to be pertinent in the area of information management, as part of a tradition of the ‘caring professional’ with all the gender implications of that concept. Role models, behaviour and expectations are also influenced heavily by these constructs around issues of gender.

Work and our choices within the world of work also drive other processes. The desire for promotion helps contribute to continuing professional development, to acquiring additional qualifications, to enhancing existing skills or to acquiring new ones, to being professionally active, to supporting other members of the professions, to being mobile, to enabling workers to have a wide range of experiences in different organizations and locations, and to enhancing their economic leverage. Conversely, choices are made which reflect different internal needs and drives. Decisions may be made which avoid promotion, responsibilities, large organizations, decision making or professional development, and which concentrate very much on personal and/or family or community pleasures and interests.

For some, work and the world of work is a clear indication of social standing and meaning (indicated by social status or salary, and therefore ‘worth’) or aspiration, linked to a strong need for recognition of the self. For some it represents status or power. It may also be an avenue to obtaining approval if this is important, which has not been given by significant others, such as parents or partner. For others, work symbolizes control, as indicated earlier. It can also be an identity, where work and the person become one and the same, and are not differentiated. It can also be used to demonstrate competitive elements of the persona which cannot be expressed elsewhere in the family or social context, but which are safely expressed at work. It may be a way of establishing and expressing self-esteem and satisfaction, if this is not possible elsewhere. Work may also be a symbolic safety net, where a job which can be well done counterbalances real or imagined failures in other parts of a person’s life. Fear of failing in relation to family, parents or children can be compensated for in this way. For the majority it is, however, a real economic driver, representing economic and personal security, as well as familial economic security. Unions are also playing an increasingly important role in career development, recognizing that this supports economic growth for their members, as well as social cohesion.

WORK AND SELF

Such experiences are different for all of us, but it is clear that there is a complex range of ways in which work is used to express thoughts and feelings. Some are clearly observable, while others are more complex or more effectively disguised. The differences in observable behaviours are a result of our own experiences and backgrounds, as well as our own intellectual, emotional and psychological frameworks. An understanding of some of these experiences and the feelings which fuel our behaviour and ambitions, enable us to begin to accept some of our strengths and weaknesses and to begin to see work as part of our own persona.

Professional cultures and organizations are outward expressions of the individual. They reflect human experiences in a range of contexts. The results of these engagements may be pleasure or pain, or conflict or resolution. The engagements may result in satisfactory careers or work experiences, or merely an unsatisfactory set of economic experiences. An understanding of some psychoanalytic theories can help to illuminate conflicts, difficulties and pleasures, and recognize some of the ways in which work and organizations affect workers and their careers. It can also help to illuminate the relationships between the individuals and career development.

Through an understanding of some of these theories, the external reality of work experiences can be seen to illustrate some of the many ways in which work expresses internal symbolic experiences. These internal experiences underpin the actual experiences, decisions, choices and developments at work. So the external becomes a manifestation of the internal, experienced at unconscious levels.

One clear example is the worker who seeks perfection, and who perceives control of events, people, organization or other elements at work as a way of achieving this perfection. This may relate to a range of experiences, probably including not having been valued sufficiently as a child or adolescent. Work then becomes a way of dealing with this strong need for recognition and approval.

So it can be seen that the world of work is both real, in its relationship to external experiences and organization, observed and observable, and unreal, in that it reflects individual and unseen internal needs and experiences. The process of linking these two elements and understanding their relationship is key to understanding the individual career. For the individual, the choice of work and career, the drivers which help to determine choices, the progression of career, or the lack of career, change of career, or maintaining several careers, or the abandonment of career, reflect both these real external worlds, and the individual internal worlds.

For the information professions, as for other professions, work now takes place within a rapidly changing environment. Everyone is aware of these changes in the post-modern world, touched on above. These also include consumerism and customization, technology, knowledge management, virtual organizations and experiences, public/private partnerships, competition, changing cultures, a recognition of the importance of research, stakeholder involvement, competitive organizations, and the resultant creativity as well as the tensions and paradoxes that these produce. Within this context, the further exploration of the relationship between the identified external realities and internal issues provides the basis for this first chapter. The book then continues to focus on a range of issues which inform and affect the careers and career development of information professionals within this rapidly changing environment.

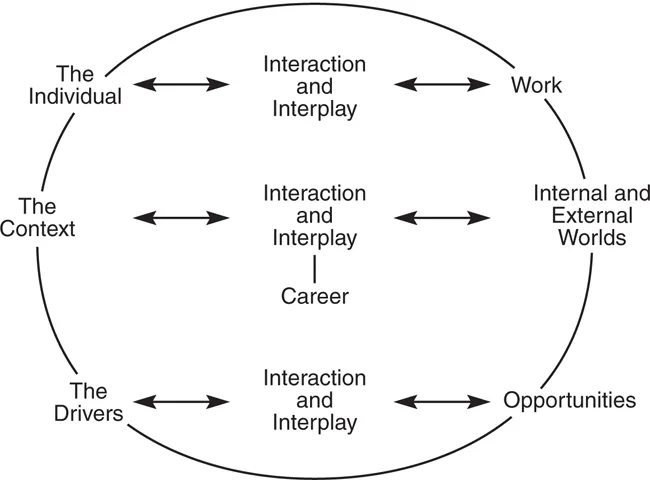

As suggested in Figure 1.1, linked to these elements of change are the parallel changes required in the workforce and the individual. Changing work requires changing skills and competencies, as well as personal attributes. Qualities such as leadership, creativity, versatility, flexibility, team working and political awareness have been identified by employers, employers’ federations and anyone involved in managing workers in a context of change. Key skills and competencies such as management, transferability, financial ability, communication and interpersonal and political skills, to name but a few, have also been identified by employers in feedback and reports. These identified changes are followed by the debates on where and when and how they can be clearly identified, developed, transferred, imbued, offered as training, developed as part of career development, learned through experience or through academic routes. The growth in MBA degrees is an illustration of the need to support such changes within a formal framework. The debates also cross more traditional professional boundaries by identifying personal qualities, specific cognitive transferable skills (technological and organizational), linked by the phantasy of what is needed in the ‘ideal’ worker and workforce.

Individuals are increasingly having to analyse themselves in relation to the changing environment. This involves identifying gaps and weaknesses, developing these and then moving into advanced or new areas of expertise. Talent management is a key element for the modern information worker. This process is encouraged by forward-thinking employers as creative employees contribute to developments. The drivers shaping and determining these changes and debates are universal, including those identified earlier, and others such as the need for flatter and more flexible organizations, profits, market forces, political policies, and the management of and access to information. They all affect career development and organizational development as well as personal change. They also inform debates on careers, as well as providing creativity or tension. Resolving tension can in turn lead to further creativity.

Accepted psychodynamic theories form the basis for the exploration of the relationships between the external observable and real world of work, and the more difficult area of the unconscious world. The majority of psychodynamic theories stem largely from the work of Freud, as well as from earlier work which he incorporated into his research. Many developments in thinking have taken place since then, and some concepts negated, but some core concepts remain unchanged. The basic premise is that individuals operate in two differing but interacting worlds. Both can be identified, and they interact with each other in different ways for different individuals. The external world is largely the conscious world in which work plays such a large part. The inner world, largely unconscious, strongly influences the actions and choices in the external and work-based world of the individual.

As already indicated, these worlds are dynamically linked, and usually are in some kind of balance or equilibrium. Some experiences and choices at work can alter or upset this balance, and some understanding of the relationship between the two worlds makes it easier to cope with conscious decisions made at work or home. Work tends to occupy much of an individual’s time; and the relationships within work, perceptions of the self, perceptions of the organization, of the other workers, expression of emotions, the need to achieve, or not, are all expressions of the dynamic between these worlds.

In the world of work, careers and career development, there are many clear manifestations of these relationships between what is seen and done, and the underlying personal drives that lead to these behaviours and work and career patterns. If some of these familiar patterns can be analysed and recognized, they can provide a basis for further consideration of such relationships. This then supports career development and growth. It is of course important to distinguish between superficial analyses and more detailed personal explorations, but some patterns do reoccur, and can support further personal and organizational exploration.

Some of the descriptors used above can be grouped into positive experiences (development, fulfilment, commitment, love, transformation) or negative experiences and feelings about work (unemployment, fear, rejection, slavery), while others describe the sense of being caught up in a network which can submerge the individual. These feelings are part of an even more complex set of emotions, but within all of these are some clear threads which emerge in patterns of behaviour at work, and which are the result of internal emotions.

WORK – POSITIVE PROCESSES AND EXPERIENCES

For many people work can be a very positive and enriching experience. For example, it frequently provides a learning framewor...