![]()

p.11

Part I

Violence in schools

Introduction

This first part of the book sets the scene for the subsequent parts. It reviews some of the fundamental questions and problems that the positive peace framework and iPEACE model set out to address. It asks about the extent of conflict and violence in schools, and where they originate. Does violence come from young people, teachers, parents, members of the community or the media? Or does it rather originate in systems and cultures of schooling at local, national and international level? These questions are important, because the ways in which violence is framed have a significant impact on its responses. If violence is attributed to the wrong origins and causes, interventions will ultimately fail. This part of the book will suggest that many of the initiatives targeting violence in schools may well be misguided, due to an overly simplistic understanding of what is involved.

![]()

p.13

Chapter 1

School violence

(former teacher Ian Corcoran)

Introduction

This alarming quote came from the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire television series on 24 September 2015. This chapter reviews the extent to which such incidents have become common in schools in the United Kingdom (UK) and elsewhere. Are schools really such violent places, and is violence increasing? The media certainly creates this impression. No matter what the situation is, however, the perception of violent students is not without effects, and this chapter will end with discussion of the ways in which these discourses impact on the lives of young people and teachers in schools.

Violent students?

The Victoria Derbyshire television series, cited above, drew on a freedom of information request to 32 police forces in the UK. The reporter Nicola Beckford wanted to know how many alleged crimes linked to schools were reported to police in 2014. The results are worrying – 30,000 incidents in one year. This is equivalent to 160 allegations per school day, with theft and violent crime the most common types of offence to be reported. This is doubly concerning, considering that most schools probably avoid contacting the police because of the damaging effects of negative press.

The statistics collated by the BBC show that theft was the most common offence, with 13,003 incidents reported. There were 9,319 reports of violent crime, 4,106 reports of criminal damage or arson and 754 drugs-related offences. Some forces did not provide data on sexual offences, but in the 25 that did, 1,502 crimes were recorded. The largest number of alleged crimes was reported to the Metropolitan Police, the Greater Manchester Police and the West Midlands Police. The figures for 2014 showed a slight increase in the total number of crimes linked to schools from 2013.

A key concern is that violence seems to be increasing amongst primary-aged (4–11-year-old) children. In July 2012, The Independent newspaper reported that in the UK around 89 youngsters aged between 5 and 11 were excluded from school each day for assaulting or verbally abusing their classmates and teachers. The figures drew on 2010/11 Department for Education (DfE) government statistics, and showed that 10,090 children up to the age of 8 were given one or more fixed exclusions in 2010/11, compared to around 9,520 the year before. The 2010/11 figures include 670 children aged 4 and under, who were excluded at least once, along with 1,470 5-year-olds.

p.14

Still more alarming are the violent deaths that occur in schools. In the United States of America (USA) this has become almost normalised. Speaking after the Oregon school shooting in the USA in 2015, in which nine people were killed and seven injured before the assailant was shot dead by police, the American president Barack Obama spoke with evident frustration and distress about how “Somehow this has become routine”. The BBC news item that covered this event reported that there had been 62 shootings in US schools in 2015. In the UK, this is thankfully not a common phenomenon, but the incidents catch media attention when they do occur. There have been two teachers killed by students in the last thirty years: the first, headteacher Philip Lawrence, was stabbed to death by a teenager in December 1995 outside the gates of St George’s Catholic School while he was trying to protect a 13-year-old boy; the second, 61-year-old Ann Maguire, was stabbed repeatedly by a 16-year-old in front of a classroom of students at Corpus Christi Catholic College in Leeds in April 2014. Incidents involving students include: Bailey Gwynne, aged 16, who died after being knifed in the stomach during an altercation with a classmate at Cults Academy in Aberdeen; and a 15-year-old student who was stabbed to death during his lunch hour in a row over £10 in Newham, London in 2001.

The headlines – dramatic though they are – belie the reality for most teachers and students in schools. Student-related ‘violence’ tends to be much more about everyday indiscipline, bullying and disruption. Teachers cite pervasive indiscipline as a reason for leaving the profession more often than fear of serious or dramatic incidents. Students also report the misery of verbal, psychological and cyber-bullying more often than serious physical attacks. This is not a situation that is limited to the UK. In 2003, Peter Smith carried out a review of violence in all fifteen (then) member states in Europe, and two associated states, under the EU Fifth Framework programme of research activities. It showed, for example, that: 12 per cent of students admitted to bullying other students regularly or often in Belgium and Austria; 22 per cent of students had been victims of sexual harassment by boys at least once in the Netherlands; and, in Spain, 72 per cent of teachers considered a lack of discipline in schools to be a serious problem.

According to a survey carried out by a UK teachers’ union, the Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL), low-level disruption is endemic in UK schools. The survey investigated behaviour in schools, and was distributed to over 1,108 primary, secondary and further education staff working in state and independent schools and colleges in the UK between 15 February and 12 March 2010. It found that 89 per cent of the teachers surveyed had dealt with disruptive behaviour in that academic year, and that almost half of them felt that disruption was getting worse. Other data from the survey indicate that low-level disruption is only slightly higher in secondary schools (91.2 per cent) than primary (86.2 per cent), and that physical aggression is higher in primary (48.3 per cent) than in secondary schools (19.8 per cent). In the independent sector, low-level disruption occurs at a similar level to the state sector, but physical aggression is significantly less (9.5 per cent as opposed to 31.7 per cent). All of the above suggests that, although serious violence in schools is very rare, low-level disruption and indiscipline are resulting in unacceptably high levels of stress among the teaching profession. This is, of course, a cause for concern.

The key questions that remain, then, are: is violence in schools getting worse; and, if so, what can be done about it? Reviewing the European research cited above, Smith (2003) notes that it is not clear whether violence is getting worse, although many people perceive it to be so. The role of the media in this was highlighted by the Portuguese contributors, who noted that “the excessive media attention, and the use of school violence as a political argument, makes the phenomenon appear larger than it really is and contributes to the growing feeling of insecurity, which is not really supported by data” (Sebastião et al., 2003: 133). There were similar findings in France. Although statistics about violence in schools in France look shocking (with a total of 240,000 incidents registered with central government in 1999), in actual fact there was less reported violence in schools than in the communities they served. School was thus one of the safest places to be.

p.15

It is perhaps interesting to note that every generation of parents and teachers seem to continue the discourse that young people are not as polite/cooperative/respectful as they used to be. The feeling that things have recently got worse in schools is an oft-repeated mantra. For example, the Elton Report (DES, 1989) was commissioned at the end of the 1980s because of public concern that violence and indiscipline in schools were getting worse. The report did not show this, but did find that low-level disruption was an issue. Although the survey methods make it hard to compare, the percentages appear quite similar to more recent statistics over 25 years later. The overall picture is thus one of stability, not of deterioration.

A piece of research that is particularly useful for this topic is Brown and Winterton’s Insight review into violence in schools for the British Education Research Association (BERA) in 2010. It reports on a meta-analysis of studies in UK schools at the time. Evidence was reviewed from a variety of sources, including youth surveys funded by government agencies such as the Youth Justice Board and the Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted), smaller qualitative studies of young people known to be at risk of violence and victimisation, and large-scale surveys undertaken by academics and teaching unions. The findings support the view that violence in schools is not as serious as many would fear, although the authors are cautious in their claims because of the methodological difficulties in carrying out this research. For example, definitions of bullying vary between studies, as do research methods, sample sizes and timeframes. This makes it difficult to compare and synthesise data. Also, much of the survey data is self-reported, which risks error due to exaggeration, lack of memory or differences in perspectives between researchers and respondents about what counts, for example, as intimidation or sexual harassment.

Research commissioned by teachers’ unions may over-represent levels of stress, threat and violence due to the need to improve working conditions. Likewise, school exclusion data needs to be treated with caution, because of political pressure to reduce exclusions at various times. In addition, there are gaps in research about topics that are less likely to attract funding (such as violence by adults against young people), and a confusing array of studies in those areas that are highly fundable (such as levels of bullying among young people, especially those who are socially excluded). The caution of the authors of the BERA report is necessary; these are contested areas that should be acknowledged. Nevertheless, the report reveals some interesting findings.

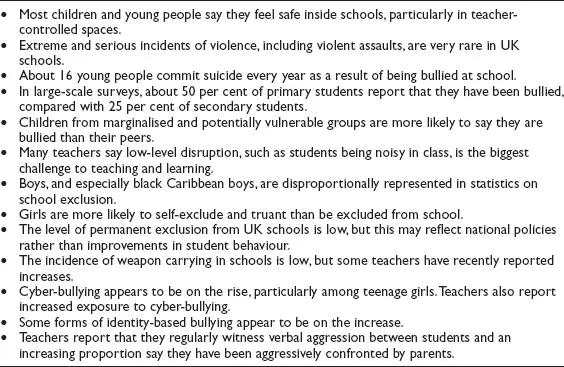

The key findings from the BERA review are shown in Table 1.1. Overall, they corroborate other studies which suggest that extreme cases of violence, including severe bullying leading to death, are very rare in UK schools. By contrast, low-level disruption, verbal aggression (for example, between students and towards teachers) and cyber-bullying appear to be areas that warrant further attention.

p.16

Table 1.1 Key findings from BERA review into violence in schools

These findings suggest that violence in schools, damaging as it is for those who experience it, is not as prevalent as many would claim.

Policy to address violence in schools

It is unfortunate that public perception seems to be at odds with reality. It is doubly unfortunate that this has been allowed to drive policy and funding. Interventions to reduce perceptions of violence in schools are not without effect. They often set a climate of fear, suspicion and intolerance. The negative effects of these initiatives are particularly felt by socially excluded groups in society, but they affect all students through the climate that they establish. This constitutes a form of cultural violence.

For example, in 2010, the UK’s Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government responded to concerns about violence in schools through its DfE White Paper The Importance of Teaching, followed by the Education Act 2011. In it they start from the premise of violent students, and outline measures to ensure that teachers will have new powers, which are akin to those of the police and security forces:

• Teachers will be given greater authority to discipline students, including an expansion of search powers, a removal of the need to give 24 hours’ notice of detentions and clearer instructions on the use of force.

• Teachers will be granted anonymity when they are accused by students.

• Headteachers will be given new powers to maintain discipline beyond the school gates.

p.17

• Headteachers will be expected to take a strong stand against bullying, particularly prejudiced-based racist, sexist and homophobic bullying.

• Ofsted inspections will focus more heavily on behaviour and safety, including bullying.

• The system of independent appeals panels for exclusions will be changed so they take less time, and students who commit serious offences cannot be re-instated.

• A new approach to permanent exclusions will be piloted, giving schools the power, money and responsibility to secure alternative provision for excluded students.

The tenor of the White Paper is that adults must regain control and replace softly-softly approaches with increased disciplinary measures. The implication is that teachers have lost authority and the power to ensure a safe and productive working environment for students (Stanfield and Cremin, 2013). Another more recent example is an incident in which the UK government Department for Education issued guidance on exclusion, only to be forced to withdraw it a few weeks later. It had attempted to further reinforce a headteacher’s right to exclude, and the ease with which this could be done, but the guidance was found to have been introduced without the required consultation. The increasingly authoritarian tone of government guidance, here and elsewhere, is concerning, especially when it leads to increased security and surveillance, and to new powers to exclude young people who may already be socially excluded.

Another strategy suggested in the 2010 White Paper to decrease levels of violence in schools is the fast-tracking of ex-soldiers into the teaching profession through the ‘Troops to Teachers’ programme. Section 2.15 says:

(DfE, 2010: 2.15)

Leaving the recruitment and training issues aside, the implications he...