![]()

SECTION III

Peripheral Occlusive Disease

![]()

14

Acute arterial insufficiency

MARK M. ARCHIE and JANE K. YANG

CONTENTS

Etiology

Pathophysiology

Diagnosis

Treatment

Fibrinolytic therapy

Embolectomy

Thrombolytic therapy versus surgical intervention for acute arterial insufficiency

Post-operative anticoagulation

Fasciotomy

Pediatric population

Upper extremity ischemia

Cerebral ischemia

Visceral ischemia

References

Whenever the motion of the blood in the arteries is impeded, by compression, by infarction, or by interception, there is less pulsation distally, since the beat of the arteries is nothing else than the impulse of blood in these vessels.

William Harvey

Acute arterial insufficiency remains a morbid disease; 30-day mortality remains nearly 15% with an amputation rate of 10%–30%.1 There has, however, been marked improvement in the treatment options, decreasing the morbidity and mortality that the treatment itself brings. The most significant progress in limb salvage for acute arterial ischemia came about with two developments in the twentieth century. First, heparin anticoagulation has made it possible to limit the propagation of clot distal to the point of occlusion and to reduce the incidence of recurrent embolus and thrombosis. Second, the Fogarty balloon catheter, introduced in 1963, made it possible to extract emboli and thrombi from arteries, with a device far better suited for this purpose than the devices used in the past such as corkscrew wires or suction catheters.2 Furthermore, the expanding array of endovascular techniques and their successes in chronic peripheral arterial disease have created increasing minimally invasive options for acute arterial insufficiency as well. This chapter describes the etiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and current procedures for treatment of acute arterial insufficiency.

ETIOLOGY

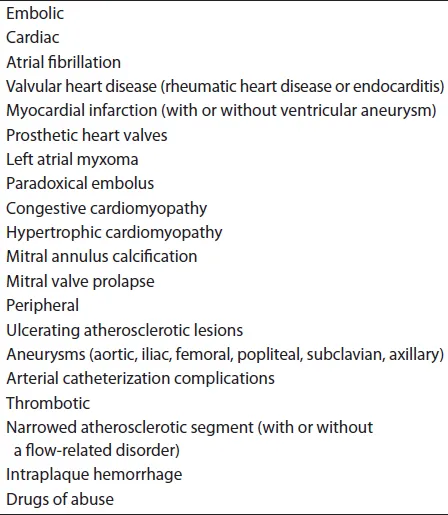

Acute arterial ischemia is caused by one of three general etiologies: acute thrombosis, emboli or trauma (Table 14.1). Acute thrombosis is currently the most common cause of acute arterial insufficiency, cited at up to 60% of acute ischemic episodes reported. Thrombosis usually occurs at a point of narrowing in a progressively atherosclerotic vessel, particularly in association with a flow-related disorder, such as congestive heart failure, shock, dehydration or polycythemia. Hemorrhage within a ruptured atheromatous plaque can cause acute occlusion, as can dissection and hypercoagulability.

Anticoagulation for these cardiac diseases has dropped emboli from the most common to the second most common cause of acute arterial insufficiency. Emboli can be of cardiac or non-cardiac origin. In the past, approximately 75%–80% of all emboli originated from the heart, the majority of those being of left atrial origin in patients with rheumatic heart disease and atrial fibrillation. With the decreased incidence of rheumatic heart disease, the most common cardiac source of an embolus is seen in the diseased myocardium, due to hypokinesis and stasis of blood, with atrial fibrillation being most commonly caused by coronary artery disease.3 The most common non-cardiac sources of arterial emboli include debris from ulcerating atheromatous plaques in the aorta and common iliac arteries. These lesions may be associated with aneurysmal disease of the proximal circulation, as well as more distal vessels, such as the popliteal artery. Other sources or causes of emboli are listed in Table 14.1 and include atrial myxoma, endocarditis, prosthetic heart valves, complications of arterial catheterization and paradoxical embolization. In approximately 25% of cases of acute ischemia caused by embolism, no source for the embolus can be identified. These cases may be due to small ulcerative lesions not demonstrated angiographically or may be caused by paradoxical emboli in which a septal defect cannot be identified.

Table 14.1 Etiology of acute arterial occlusion.

Trauma-induced arterial insufficiency will be discussed in a later chapter.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The source of emboli, more often than not, dictates which arteries are affected and subsequently, the deficits encountered. Occlusions found at the bifurcations of large arteries are mainly of cardiac origin, while those of more distal, smaller vessels can be attributed to atheroemboli from atherosclerotic plaques (cholesterol embolization syndrome). The size of the obstructed vessel then can help in differentiating between emboli that originate from the heart and emboli that originate from the aorta or common iliac arteries. For example, an embolus that lodges in the common femoral artery, a medium-sized artery, is usually of cardiac origin. An embolus that leads to ischemia of an isolated toe most likely originates from the distal aorta or common iliac arteries. Thrombosis will often present with milder limb ischemia than emboli because of the chronic nature of the underlying atherosclerotic lesions. Patients with longstanding arteriosclerosis often have a complex collateral circulation in place.

Once an embolus or thrombus occludes an artery, the distal vasculature goes into spasm. Extension of the thromboembolus then forms proximal to the site of occlusion, back to the point of adequate collateralization. The distal spasm lasts for approximately 8 hours and then subsides. At this point, clot forms in the arterial system distal to the site of obstruction and propagates downward, obstructing any residual collateral flow, resulting in worsening of the ischemia. As a result, the skin usually becomes patchy, blue and mottled. Skeletal muscle and peripheral nerves withstand acute ischemia for some 8 hours without permanent damage; skin can withstand severe ischemia for as long as 24 hours. The extent of the ischemic necrosis depends on the adequacy of collateral circulation, the patient’s underlying cardiovascular function, viscosity of the blood, oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, propagation of clot into the microvasculature and effectiveness and promptness of treatment.

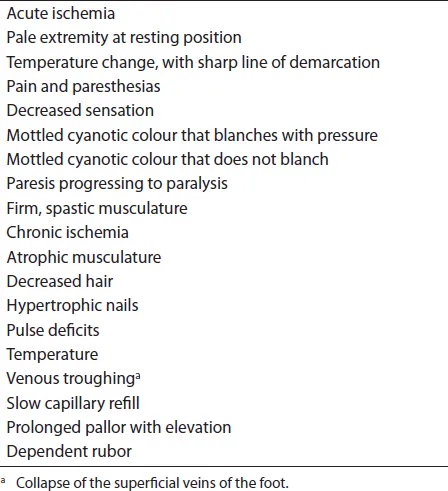

If muscle ischemia progresses to necrosis, the muscle becomes paralyzed and acquires a firm, spastic consistency. When peripheral nerves become ischemic, they cease to function, and the affected parts become anesthetized. As the skin undergoes profound ischemia, maximum oxygen extraction results in a cyanotic, blotchy appearance. When these blotchy, cyanotic areas no longer blanch with pressure, the skin is gangrenous and the ischemia is no longer reversible.4

The reperfusion of ischemic muscle poses a threat to other organ systems.5,6 Anaerobic metabolism produces unbuffered acid, dead cells release potassium and myoglobin, microthrombi form in the areas of stasis and acidosis, and procoagulants and inflammatory products accumulate. With reperfusion, oxygen radicals, leukotrienes and many other inflammatory mediators are generated, and all of these products are released into the systemic circulation. Here they produce systemic vascular permeability, extravasation of plasma into the interstitium and damage to remote organs. The lungs receive the initial insult, with further damage occurring in the heart and kidneys.7 A mortality rate of 85% when a limb with advanced ischemia is revascularized has been documented. The degree of insult to the body as a whole depends upon the mass of ischemic tissue, the duration of the ischemia and the underlying condition of the remote organs.

DIAGNOSIS

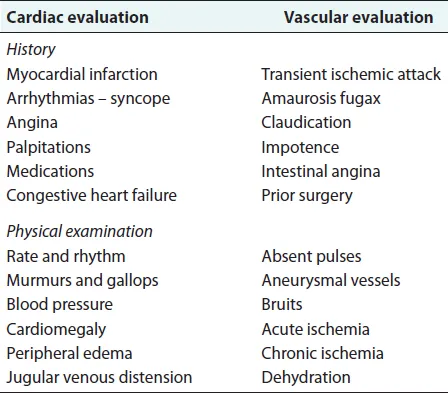

In most cases, the history and physical examination allow identification of the level of obstruction, the probable cause and the degree of ischemia (Tables 14.2 and 14.3). This information usually dictates the extent and mode of therapy.

The history should review the duration and progression of the symptoms and should document prior cardiac or vascular disease that might complicate the treatment. A history of claudication indicates prior atherosclerotic disease and points towards superimposed thrombosis as the culprit. In a nonsmoker, aortoiliac occlusive disease is unlikely. A history of heart disease, particularly one associated with arrhythmias, makes the possibility of embolization from the heart likely.

Table 14.2 Signs of ischemia.

Table 14.3 Patient evaluation.

The physical examination may give information regarding any cardiac disease and the likelihood that the heart is the source of an embolus. Signs of chronic ischemia in the lower extremities, hypertrophic nails, atrophic skin and hair loss indicate chronic obstructive disease.

The presence of acute arterial insufficiency is usually manifested by an abrupt temperature change in an extremity distal to the level of the obstruction (Figure 14.1). The ability to dorsiflex and plantarflex the toes indicates the viability of the musculature in the calves; the inability to move the toes indicates impending necrosis of a muscle group. Development of firm, spastic musculature, especially if the contralateral side is normal, indicates extensive necrosis or impending acute compartment syndrome (ACS).

Paresthesias and anesthesia indicate that the nerves have undergone ischemic changes. Waxy, white skin is characteristic of active arteriolar spasm and indicates viability of arterioles to the skin. Blotchy cyanosis that does not blanch with pressure indicates thrombosed capillaries in the subcuticular areas and skin necrosis.

Laboratory tests are aimed at evaluating fluid balance, oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood, renal function, cardiac function and muscular damage (Table 14.4). A chest x-ray shows the size of the heart and may identify thoracic aortic disease. A hematocrit can make a diagnosis of polycythemia. A urinalysis that shows protein and pigment suggests the presence of myoglobin in the urine. The determination of creatinine phosphokinase with isoenzymes can give information about muscle necrosis. An electrocardiogram defines arrhythmias and gives information about the status of the heart. Two-dimensional echocardiography identifies the cardiac chamber size, estimates the ejection fraction, studies the valvular pathology, evaluates the wall motion and sometimes identifies intracardiac thrombus or tumor.8,9 Echocardiography may also detect a potentially patent atrial septal defect, which may be involved in a paroxysmal embolus. Echocardiography is not helpful acutely in deciding whether to operate, anticoagulate...