eBook - ePub

Tribosystem Analysis

A Practical Approach to the Diagnosis of Wear Problems

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Tribosystem Analysis: A Practical Approach to the Diagnosis of Wear Problems provides a systematic framework for conducting root cause analyses and categorizing various types of wear. Designed specifically for engineers without formal training in tribology, this book:

- Describes a number of direct and indirect methods for detecting and quantifying wear problems

- Surveys different microscopy techniques, including those for light optics, electron optics, and acoustic imaging

- Discusses the selection of wear and friction test methods, both standard and custom, identifying possible pitfalls for misuse

- Presents practical examples involving complex materials and environments, such as those with variable loads and operating conditions

- Uses universally accepted terminology to create consistency along with the potential to recognize similar problems and apply comparable solutions

Complete with checklists to ensure the right questions are asked during diagnosis, Tribosystem Analysis: A Practical Approach to the Diagnosis of Wear Problems offers pragmatic guidance for defining wear problems in the context of the materials and their surroundings.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tribosystem Analysis by Peter J. Blau in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Industrial Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 What Is a Tribosystem?

Sooner or later, everyone experiences a friction or wear problem. What people choose to do about it is a different matter. You could simply ignore the problem or discard the worn-out device. If that is not an option, then you can replace the part or the entire device with a new one. As an engineer who needs to dig deeper into the problem, you may decide to improve the component design, try a different lubricant, or consider using alternative materials, surface treatments, finishes, or coatings. This book is intended to help those who need to do something about a wear (or friction) problem, whether it involves understanding how it happened, diagnosing the kind of wear that is occurring, developing or using a test to select alternate materials or lubricants, or completing a root cause analysis that could eventually lead to longer product life, improved design, and greater component reliability.

Wear problems belong to the multidisciplinary field of science and engineering that is called “tribology.” Its name derives from the Greek word tribos, which in English means “I rub.” The word tribosystem refers to a physical arrangement of two or more interacting structural parts, including the materials of which they are composed and the environment in which friction and wear is occurring.

ASTM terminology standard G40-15 [1] formally defines a tribosystem as follows:

tribosystem, n.—any system that contains one or more triboelements, including all mechanical, chemical, and environmental factors relevant to tribological behavior.

And it goes on to define triboelement as follows:

triboelement, n.—one of two or more solid bodies comprising a sliding, rolling, or abrasive contact, or a body subjected to impingement or cavitation. (Each triboelement contains one or more tribosurfaces.) Discussion—Contacting triboelements may be in direct contact or may be separated by an intervening lubricant, oxide, or other film that affects tribological interaction between them.

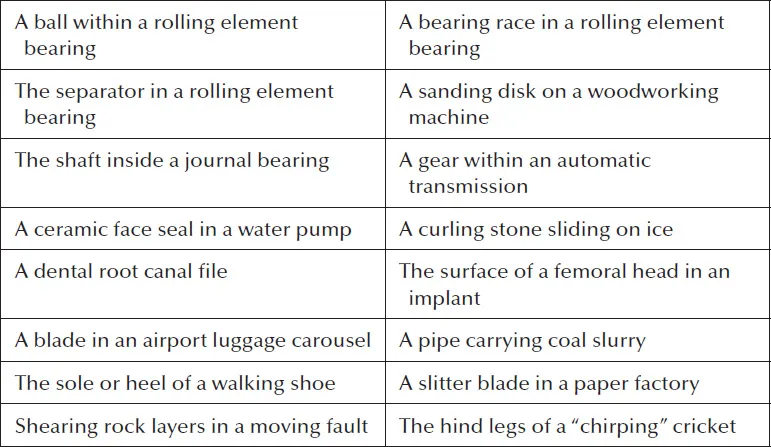

Examples of triboelements include the following:

From a macroscopic point of view, a complex mechanical device like an engine, a pump, or a gearbox can be composed of more than one (sub)tribo-system, each of which contains a number of discrete triboelements. Thus, the definition of a tribosystem's boundaries is more obvious in some cases and less so in others. However, a working definition should include all the components and materials that surround the tribological interface of interest and that could influence its friction or wear behavior. That is, to establish the boundaries of a tribosystem, it is usually best to begin with the contacting surface(s) of interest and work outward.

In his book on wear analysis, Bayer [2] distinguishes between a macrotribosys-tem and a microtribosystem, with the latter being the contact zone experiencing friction or wear and the former containing the surrounding parts of the device. The exercise of defining a tribosystem's boundaries can be helpful when troubleshooting because it forces one to consider both internal and external influences.

One example of a complex tribosystem whose subassemblies can be considered tribosystems in and of themselves is the automatic transmission in an automobile. A conventional automatic transmission consists of a torque converter, a planetary gearset, clutches and bands, and the fluid system, which includes a pump and the associated valve body. Any assembly of individual gears (triboelements) could be considered a tribosystem, as could a clutch, or a seal, or a set of bearings that operate within that transmission. If a particular gear might be more problematic than others, then it would be appropriate to narrow the tribosystem of interest to include that gear and the surrounding gear or gears that come into contact with it. In bench-scale laboratory testing, the definition of tribosystem is more straightforward: The tribosystem is the test apparatus, the materials and any lubricants within it, and the immediate surroundings.

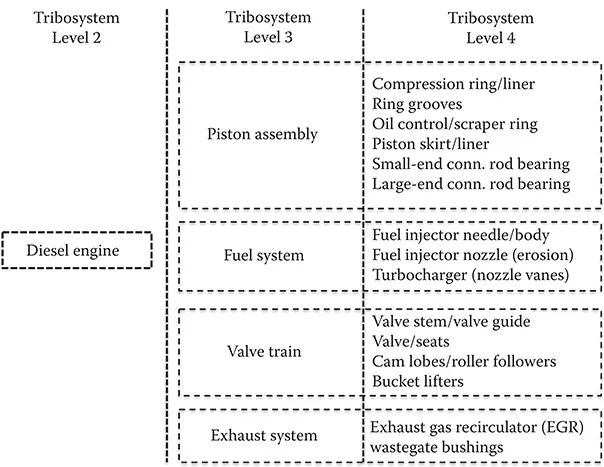

Figure 1.1 shows how a large and complex machine can be partitioned into a series of smaller tribosystems, each having its own functional requirements, surroundings, operating conditions, and materials. In this case, level 1 (not shown in the figure) would be the entire vehicle. Level 2 (one of several subtribosystems) shows just the engine. Owing to the large number of friction and wear interfaces involved, multiple types of wear can occur even within the same subtribosystem. For example, a piston ring in a ring groove in level 4 could experience microweld-ing, impact, rocking, circumferential slip, and fretting. Therefore, the process of conducting a tribosystem analysis is not limited to discovering only one dominant type of wear or surface damage, but rather identifying any and all relevant influences on the desired function of that tribosystem.

A similar approach to that in Figure 1.1 has been taken to categorize test methods that simulate practical tribology problems. For example, German standard 50 322 [3] has proposed six levels of tribotesting, ranging from full-scale machinery operating in the field to small coupons in bench-scale experiments. As will be discussed later in this book, the effectiveness of a simulation in obtaining meaningful data to screen or select materials or lubricants in practical tribology problem solving depends on matching the key characteristics of the engineering tribosystem with those of the test bench, which is its own tribosystem.

Figure 1.1 An example of how a large tribosystem can be broken down into sublevÉis containing smaller tribosystems. Level 1, not shown in the figure, is the entire vehicle, the driver, and its environment.

When diagnosing wear problems, especially those concerning lubricants, tri-bosystems can be characterized as being either open or closed [4]. Open systems have the potential to introduce contaminants or chemical species into the tribo-system while operating. For example, jaw crushers in ore processing or recycling plants are continually being fed new rock, and the composition of the foreign bodies in the input stream may contain unexpected wear-causing materials, like nuts, bolts, or spalled wear plates broken off upstream from the mining equipment itself. Likewise, rolling mill rolls could pick up mill scale or hard particles from elsewhere in the plant.

A transmission fluid pump with a recirculating working fluid and a bearing that is “sealed for life” are examples of closed tribosystems. Some systems have both open and closed characteristics. Internal combustion engines contain recirculating oil and coolant systems, but there is a potential to introduce wear-causing material through the fuel or air intake if filters are not working properly. Obviously, wear debris particles can be generated in both open and closed tribosystems. Years ago, an automotive engine manufacturer had postmanufacturing problems with leftover casting sand from the cylinder blocks finding its way into their engines. Here, an external source of abradants produced wear in what is designed to be a closed tribosystem.

The primary goal of this book is to present a systematic approach for defining tribosystems and their characteristics. In that way, root cause analyses and tribolog-ical problem solving can be facilitated, as can the selection of materials, lubricants, and test methods for use in evaluating candidate solutions. While the flexibility of the approach makes it useful for attacking both basic and applied tribology problems, the emphasis in this book is mainly on engineering challenges.

Having established the concept of a tribosystem, the rest of this book is focused on how that basic concept can be applied to analyze and diagnose wear problems. Chapter 2 describes how wear problems present themselves. It includes a discussion of how wear problems are detected, quantified, and monitored. Chapter 3 presents the author's approach to categorizing wear or surface damage based on the type of relative motion that is producing them and their observed features or artifacts. It discusses the role of terminology in the process, including both formal definitions and field-specific jargon, and it introduces a coding system that can provide a measure of consistency and a shorthand system for identifying the type(s) of wear. Since visual observations, both unaided and aided, are key in the diagnosis of wear and surface damage, Chapter 4 highlights a range of surface imaging tools, specimen preparation methods, and their practical advantages and shortcomings. Chapter 5 describes the tribosystem analysis form and how tribosystems, even relatively complex ones, can be characterized. Chapter 6 adds a discussion of problem-solving options, the selection and types of information available from wear testing, and a few examples of matching the performance of large-scale tribosystems with data from simulative test methods.

Finding solutions to wear problems is not equivalent to solving friction problems, but a tribosystem analysis approach can be applied to define friction-critical situations as well. (Recall that the word tribology has its roots in the Greek word for rubbing with friction.) As will be discussed later, friction is a manifestation of the energy available to do work between rubbing materials, and creating wear particles is one of the ways (but not the only way) in which that energy is dissipated. Therefore, the relationship between friction and wear varies depending on the nature of each tribosystem, and many similar concerns are involved in both friction problem diagnosis and wear problem analysis. At the center of it all is the notion of a properly functioning tribosystem and how the knowledge of its details enables one to improve its performance.

References

ASTM G40-15 (2015) “Terminology relating to wear and erosion,” in ASTM Annual Book of Standards, Vol. 03.02, ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, p. 164, http://www.astm.org/BOOKSTORE/.

R. G. Bayer (2002) Wear Analysis for Engineers, HNB Publishing, New York, Chapter 3.1.

“Kategorien der Verschleifiprufung,” Standard DIN 50 322, Deutsche Inst. fur Normen, Berlin, Germany.

P. J. Blau (1989) Friction and Wear Transitions of Materials: Break-in, Run-in, Wear-in, Noyes Publications, Saddle River, NJ.

2 How Wear Problems Reveal Themselves

Tribosystem analysis (TSA) is basically a process to dissect and organize the mechanical, chemical, thermal, and materials-related aspects of a wear-related and/or friction-related condition. Each tribosystem analysis for wear should therefore begin by asking the fundamental question: “How do I know I have a wear problem?” The answer to that question might seem obvious at first, but the ability to detect early indications of wear depends on where and how the problem is occurring.

Superficial indications of wear, like tire wear patterns or marred paint finishes, are easily seen, but in many practical cases, the first indications of a wear problem lie deep inside a machine. They are more subtle and, for all practical purposes, impossible to detect until more serious problems occur downstream. This chapter overviews the kinds of indications that reveal a developing wear problem. These involve the human senses of sight, hearing, smell, and touch. Even taste can be involved if lubricant or wear debris finds its way into food products or containers. In one sense, the various instruments and sensors used in machinery health diagnosis and wear analysis are an extension of the five senses.

There are both direct and indirect indications that wear is occurring. There are also quantitative and qualitative indications of wear. Some wear problems involve cosmetic indications because the function of some products includes how they look to the user. For example, a great deal of clothing is discarded because it looks worn, not because it fails to provide body coverage or warmth. Likewise, some machine components are replaced because they appear to be worn, not because they would not continue to function “mechanically” for a while longer. A disreputable auto mechanic might show you a costly transmission part from your car and claim that it is so worn that it should be replaced. Unless you have worked on automobiles and have experience in this area, few consumers have the experience to dispute such a claim. The need to do something about wear then becomes a matter of subjective judgment or trust in an “expert opinion.” We all know that this can be a costly decision and we tend to err on the conservative side if we can afford it.

There are many possible causes for excessive wear in a tribosystem, for example,

- Applying loads, speeds, or operating conditions in excess of the recommended design limits

- Loading a component in a direction other than that for which it was designed (say, an axial overload on a radial bearing)

- Loss, “starvati...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Author

- 1 What Is a Tribosystem?

- 2 How Wear Problems Reveal Themselves

- 3 Types of Surface Damage and Wear

- 4 Tools for Imaging and Characterizing Worn Surfaces

- 5 The Tribosystem Analysis Form

- 6 Wear Problem Solving— The Next Steps

- index