eBook - ePub

The Ethical Kaleidoscope

Values, Ethics, and Corporate Governance

- 590 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The study of corporate governance is a relatively modern development, with significant attention devoted to the subject only during the last fifty years. The topics covered in this volume include the purpose of the corporation, the board of directors, the role of shareholders, and more contemporary developments like hedge fund activism, the role of sovereign wealth funds, and the development of corporate governance law in what perhaps will become the dominant world economy over the next century, China. The editor has written an introductory essay which briefly describes the intellectual history of the field and analyses the material selected for the volume. The papers which have been selected present what the editor believes to be some of the best and most representative studies of the subjects covered. As a result the volume offers a rounded view of the contemporary state of the some of the dominant issues in corporate governance.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ethical Kaleidoscope by Douglas G. Long,Zivit Inbar in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

The ethical context of governance

1

Values

Values are shared abstract ideas, implicit or explicit, that serve as guiding standards to actions, evaluation of situations, events, behaviours and people. Values influence our thoughts, feelings and actions in an unconscious manner. They provide guidance in analysing situations (what is rational for us is a consequence of our values). One of the important roles of values is in shaping our ethics and ethical decision making.

Values, or knowledge, that are shared by members of a certain group and influence their behaviours, are called norms. This knowledge helps in predicting behaviours of others in different situations.1 Important norms are designed to protect society (for example, opposing murder or supporting elderly parents), less important norms cover behaviours such as manners and speech.

Unlike the motivation to conform to formal rules and regulations, the motivation to conform to social norms stems from the fear of the reaction of others in cases of deviation from these norms. According to Sunder, conformity to norms is also seen as a moral or ethical obligation. People obey and enforce a norm, because they internalise the norm in such a way that it becomes part of their preferences.

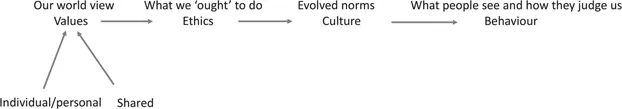

In other words, values are emotionally loaded beliefs that can change over time. Of course, these values are primarily individual and personal but there are always overlaps among people and in virtually any and every grouping of people there are significant quantities of shared values. Values reflect our world view and they frame our approach to ethics. In turn, our combined demonstration of ethics in any organisation leads to the evolution of an organisation’s culture and, eventually, it is the culture of the organisation that dictates the behaviour which determines how the organisation is perceived by others.

This is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 From values come behaviours

However, despite the term ‘values’ being freely bandied around, the concept is really quite complex.

In the years 1981–1993, Australia experienced its greatest ever rise and fall of many big-name businesses, with their failures having significant follow-on effects, not just in the Australian economy but internationally as well. The legacy of just 20 of these is a cost to their investors of around 16.5 billion Australian dollars while their costs to the banks and related financial services organisations was in excess of 28 billion Australian dollars2 – and this at a time when the Australian dollar was valued at a significantly higher rate than was the US dollar. Despite the protestations of many at the time, a financial disaster of this magnitude need not have occurred and it certainly was not simply the result of the behaviour of a relatively few isolated ‘cowboys’. The faults were systemic – and they related to values and ethics.

Trevor Sykes, a widely respected financial journalist, investigated many of these collapses for his book The Bold Riders and his data make it clear that a key reason for these failures was that many of the auditors, financiers, corporate boards and regulators involved had failed to exercise good corporate governance. They knew the law and they knew what they should be doing but, for a variety of reasons, either they failed to act appropriately or they ensured that strict adherence to the letter of the law was observed but they ignored any breaches of the spirit of the law.

In the 1987 movie, Wall Street, Gordon Gekko uses the now well-known aphorism ‘Greed is Good’ to justify his actions in making money by any means possible in order to further his desires for wealth, power and influence. The ‘bold riders’ of whom Sykes wrote certainly believed this and, in the pursuit of their wealth objectives, what many consider to be ethical behaviour was the last thing on their minds.

In 1997, Bob Garratt, a consultant advising on director development and strategic thinking, published The Fish Rots From The Head 3 in which he makes the point that many directors lose sight of the fact that, legally, they are accountable to the company itself as a legal personality. He points out that most directors see themselves as representatives of such parties as shareholders or lenders and so tend to focus on what is good for these parties rather than on what is best for the company per se in both the short and long term. A direct consequence of this is that, far too often, doing what is legal becomes conflated with doing what is ethical and this can have serious adverse implications for the company to which they are actually accountable. He specifically refers to Australia’s experience of the 1990s in this discussion.

In discussing issues impacting the running of successful companies, it is not uncommon to hear people say that the principal responsibility of boards and managers is to maximise profit so that shareholders reap high dividends from their stockholdings. That this is a naive premise can be quickly demonstrated by considering the relationship between risk and reward. The truth is that, for both short-term and long-term sustainability and success, an appropriate balance between risk and reward needs to be struck. A high level of risk in some business ventures may well have the potential to yield extremely high profits – but the downside may be total collapse of the business. For this reason, responsible boards and managers focus far more on profit optimisation that has the potential to result in wealth maximisation. Taking a more manageable degree of risk may result in lower levels of profit (in both the short and long term) but, because of good governance and sound management practices, the potential for wealth maximisation is optimised.

It was the quest for profit maximisation that drove Sykes’ ‘bold riders’4 and which led to the excesses that characterised their operations. To them, ‘wealth maximisation’ was equated with ‘profit maximisation’. Unfortunately, as Sykes makes clear, these same ‘bold riders’ had little difficulty in drawing their auditors, lawyers, banks and related financial institutions into the same quagmire. The contest became one of profit pursuit, regardless of whether or not there were appropriate business foundations or if the business was really sound. Dissenting voices were quickly hushed and, ultimately, no one had the cojones to point out that the emperor was without clothes.

If we believe the rhetoric, the collapse of the ‘bold riders’ and the collateral damage experienced by the professional services, legal entities, banks and financial services organisations provided a salutary lesson that drove the emphasis back to wealth maximisation. But, as Andrew Main made clear in two much later books,5 the problematic patterns of behaviour clearly identified by Sykes continued throughout the rest of the twentieth century.

In addition, towards the end of the 1990s we had the ‘dot com’ boom and bust and, in the first decades of the twenty-first century we have experienced the re-emergence of an emphasis on profit maximisation that, in a significant number of companies, has manifested itself as a ‘do anything it takes’ mentality to winning business in both developed and developing economies. Over the past 15 years, in Australia alone serious questions have been raised about the activities of the Australian Wheat Board in relation to trade with Iraq, of various construction companies in relation to international infrastructure deals and of a banknote printing business, which has strong connections to the Reserve Bank of Australia, in relation to the obtaining of contracts to produce polymer notes for foreign countries. At the same time, in the United Kingdom, there has been the phone hacking scandal affecting News Corporation. Then, in 2007, the USA saw the start of the disastrous global financial crisis, which reactivated the ‘greed is good’ approach and enabled a relatively small number of people across the world to make large fortunes (in part thanks to Government bail-outs) while many small investors lost everything.

And so we could continue. With monotonous regularity it seems that those involved in corporate governance and corporate management operate in ways that call into question the veracity of any stated values and ethics that are purported to underpin both their goals and their modus operandi.

In the commerce degrees at the Australian School of Business, University of New South Wales (UNSW), the subject of values and ethics is introduced as a compulsory area of study for undergraduate students. In 2015, one of the assignments related to the rationale for organisations to be seen as good corporate citizens through the implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Most students quickly ascertained that, although there were arguments both for and against CSR, the general consensus was that there were sound economic reasons underlying an organisation’s CSR activity. But when the students compared CSR activity in Australia with that outside Australia there was some amazement across the student body to discover that, at the very time they were doing the study, in the United States, New York was being brought to a standstill due to low-paid workers having to fight for an increase in their minimum hourly rate of US$8.90 – well below any form of living wage – and that, in New Zealand, it had been made legal for organisations to offer contracts to casual staff in which there are no minimum hours mandated and in which all the power rests with the employer. The overwhelming feedback from the students was that exploitation in the quest for profit maximisation indicated serious deficiencies in the values and ethics of those responsible for corporate governance and corporate management. While acknowledging that history indicates students are often idealistic, it can also be argued that values are evolving from one generation to another and it seems that this generation (called Gen Y) has a significantly higher or more developed environmental and social conscience than is found in much of the practice of conservative corporate governance.

Concurrent with this study by UNSW commerce students was an Australian Government enquiry into the behaviour of international corporations that seek to minimise their taxation liabilities by shifting profits away from Australia to those jurisdictions with the lowest corporate tax rates. Based on statements from the highest political levels in Australia, the United Kingdom and some other major economies, it seems possible that, in the not too distant future, there might be renewed examination of not only the legal basis for such transfers but also in relation to the value systems and ethics that underpin such practices of corporations.

The Davos Conference in Switzerland in 2016 focused even more attention on this shifting of profits and, indirectly, on the ethics involved by publishing a report by Oxfam6 which pointed out:

Just 62 people, 53 of them men, own as much wealth as the poorest half of the entire world population and the richest 1 per cent own more than the other 99 per cent put together, anti-poverty charity Oxfam said on Monday.

The Oxfam report suggests that global inequality has reached levels not seen in over a century.

Last year, the organisation has calculated, 62 individuals had the same wealth as 3.5 billion people, or the bottom half of humanity. The wealth of those 62 people has risen 44 per cent, or more than half a trillion dollars, over the past five years, while the wealth of the bottom half has fallen by over a trillion.

‘Far from trickling down, income and wealth are instead being sucked upwards at an alarming rate,’ the report says.

It points to a ‘global spider’s web’ of tax havens that ensures wealth stays out of reach of ordinary citizens and governments, citing a recent estimate that $US7.6 trillion ($A11.08 trillion) of individual wealth – more than the combined economies of Germany and the UK – is currently held offshore.

That same newspaper article also makes the point that:

Politicians and business leaders gathering in the Swiss Alps this week face an increasingly divided world, with the poor falling further behind the super-rich and political fissures in the United States, Europe and the Middle East running deeper than at any time in decades.

In Delivering High Performance: The Third Generation Organisation7 the point is made that it is the Chairman of an organisation who is ultimately responsible for everything that occurs within the organisation and for everything that the organisation stands for and does. This includes the values and ethics espoused by and practised throughout the organisation.

One of the things we know about values is that they can change over time. This was discussed in Leaders: Diamonds or Cubic Zirconia 8 when considering the issue of how education and life experience can bring about a difference in the way we think about things and, over time, can mean that the values driving our behaviour can change and develop.

Third Generation Leadership and the Locus of Control: Knowledge, Change and Neuroscience 9 discusses the work of Professor Clare Graves as it is expounded by Don Beck and Chris Cowan.10 Graves argued that people’s value systems (or ‘memes’) are able to change as they mature and their values acumen develops. Graves argues that the value memes fall into a series of tiers (similar in many ways to octaves in music) in which value memes are repeated at different levels. At the first level, when in any meme, a person has what could be called a monochromatic view – at any one time they are totally immersed in that meme and are unable to see beyond it. At the second level it becomes possible to see things in a more complex fashion and to recognise when and where each meme is appropriate – what could be described as a polychromatic view. In Graves’ model, the memes in each level can be described as: survival, family or tribe, power or aggression, authority or law, excellence or competition, socially responsible. All people progress through some of the levels but there is no internal or external compulsion to automatically proceed. Values acumen can develop as a person discovers that world views and behaviours that were previously appropriate are no longer sufficient and that change may be required. At this stage, a person has the choice of maintaining their values acumen at its current stage or moving to the next level. Earlier memes never disappear but they contribute to a more rich and complex set of world views and behaviours by remaining accessible along with the new meme. Beck and Cowan argue that the dominant memes in today’s world are a combination of power or aggression, authority or law, excellence or competition in their first tier format. Only a relatively small number of people and organisations will proceed to the meme of social responsibility and considerably fewer will then make the step-shift from the first to the second tier. The result is that exhortations to universal implementation of comprehensive CSR initiatives will...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Anecdotes from interviews

- PART I The ethical context of governance

- PART II The board’s role in corporate ethics

- Epilogue

- Index