![]()

Chapter 1

Why Teach about Climate Change in English Language Arts?

We don’t have a problem with economies, technology, and public policy; we have a problem with perception because not enough people really get it yet. I believe we have an opportunity right now. We are nearing the edge of a crisis but we still have an opportunity to face the greatest challenge of our generation, indeed of our century.

James Balog (Orlowski, 2012)

The debate about climate change is not about greenhouse gases and climate models alone. It is about the competing worldviews and cultural beliefs of people who must accept the science, even when it challenges those beliefs.

Andrew Hoffman (2015, p. 88–89)

With every sunrise and rotation of the Earth, humans are more interdependent on reading and writing. We are using more tools for communicating than ever before, creating increasing opportunities for people across the globe to share, organize, and solve all kinds of problems from attacks on democracy to a warming planet. These changes have moved the role of the English teacher to center stage. Humans have always been storytellers, and it has long been known that those who tell the stories control the future. It is by critically understanding the messages and stories engulfing them, and learning the skills to take action, that our students can create alternative discourses to change the present and shape the future. As English teachers, we have the potential to excite, inspire, and empower students to recognize this potential and become involved in the issue of our age, climate change and environmental justice.

Our planet has already irrevocably changed as a result of human-made emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, and other gases. Today, in line with predictions made for decades, we are seeing increasing temperatures, dramatic weather swings, devastating droughts, wildfires, huge storms, flooding, sea-level rise, warming and acidic oceans, enormous animal and plant extinctions, and more (Mann & Kump, 2015; Romm, 2015). Our planet has warmed one degree Celsius more rapidly than any time in Earth’s history, with 2016, the year we wrote this book, the hottest year in recorded history.

Recent research indicates that global temperatures may increase by 4 degrees Celsius as early as the 2070s and perhaps even sooner (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2016). A rise of 4 degrees Celsius would permanently devastate US food production, not to mention food production in other countries. The Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets have already begun to melt and break apart. No matter what humans do now, sea levels are going to rise, and rise substantially. Much of Florida and the East Coast of the United States will first be subjected to storm surges, and then inundated, as will many of the largest cities in the world (http://tinyurl.com/zbhldg5).

There is no going back. Each gallon of gasoline burned represents 100 tons of ancient plants (Dukes, 2003) and the carbon they captured being returned to the atmosphere. When carbon dioxide is released into the air it continues to affect climate for hundreds, even thousands of years. We are currently on the trajectory to 4 degrees and more. It is imperative to change what we are doing and limit temperature rise to 2 degrees. It is not certain that even with focused world attention on greenhouse gas reduction, that 2 degrees is still possible. For the sake of the human race and life on Earth, we must, nonetheless, do all within our power to limit global warming as much as possible and as soon as possible. As one of the world’s most influential climate scientists puts it, “the difference between two and four degrees is human civilization” (Marshall, 2015, p. 241).

Whatever happens, climate change will be the defining feature of the world our students inhabit. Addressing climate change is everyone’s responsibility, and that includes English teachers. As this book will show, there is much we can be doing.

We and our students can and must make a difference. We have the opportunity and obligation to educate our students about climate change; fire their imaginations, their talents, and their energies; inform our local and larger communities; and, join with others across the globe to demand and participate in one of the largest and most urgent transitions in human history.

The Crisis and the Urgency of Change

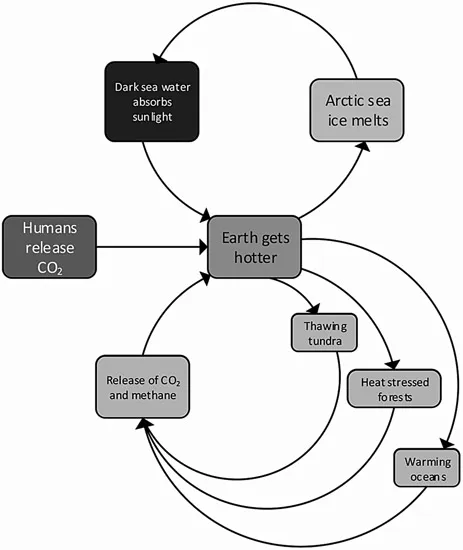

In a simple model, humans impact the climate by releasing gases which accumulate in the atmosphere and bounce solar energy back to the Earth, as in a greenhouse, making the Earth grow continually warmer. Indeed, our planet is absorbing a lot of heat, warming all ecological systems. Scientists have calculated that in recent years Earth has been gaining as much heat every day as would be released by 400,000 Hiroshima atom bombs (Romm, 2013). Human emissions cause the increased warming, and natural feedback loops speed it up even faster. Ice and snow reflect 70 percent of solar energy while the open ocean absorbs 95 percent. So as polar ice caps melt and expose more ocean, a great deal more heat is absorbed and global warming is accelerated “naturally.” Warming by human emissions releases methane, a greenhouse gas, from tundra and ocean beds, again accelerating warming (see Figure 1.1). As McCaffrey (2014) notes

The interconnectedness of Earth’s systems means that a significant change in any one component of the climate system can influence the equilibrium of the entire Earth system. Positive feedback loops can amplify these effects and trigger abrupt changes in the climate system. These complex interactions may result in climate change that is more rapid and on a larger scale than projected by current climate models.

McCaffrey (2014, p. 136)

Global warming will have devastating impact in every country. Current understanding indicates that a catastrophic world of mass starvation, mass flooding, mass migration, and mass death of hundreds of millions, perhaps billions, of people may happen much sooner than most expect, particularly in developing countries. An entire lake in Bolivia, the size of Los Angeles, is now bone dry, resulting in residents having to flee. The largest city in the western hemisphere with 20 million residents, São Paulo, Brazil, is close to running out of water. Due to rising sea levels, many of the Marshall Islands and coastal regions of Bangladesh are under water or soon will be.

Figure 1.1 Factors Impacting Climate Change

Some of the first to suffer and endure the worst effects are the poorest countries, nations that have the least responsibility for the pollution that causes climate change. Poorer countries and poorer people have fewer resources to defend themselves, so the impacts of climate change will be unfair and unbalanced. The US Military considers climate change a threat multiplier that will cause hunger and disease, increase instability, undermine governments, and intensify conflicts and terrorism. It is already doing so in the Middle East and Africa. While climate change will be disastrous for the poorest regions of the world, it will also have horrific consequences for wealthy countries, the United States included.

We know about Hurricane Andrew in Florida, Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, flooding in Baton Rouge, Superstorm Sandy in New York, the Texas drought of 2010–2014, the California drought of 2012–2016, and so on. In 2012, drought in the Great Plains and Prairies (the American “breadbasket”) led to loss of half of American food crops. The northern jet stream that meandered south during winters in 2013–2015, caused by relatively warm Arctic temperatures that weakened the polar vortex and created frigid winters in the Midwest and Northeast punctured by surprising heat, resulted in 75 degrees on Christmas Eve in New York in 2015. And we are only at one degree Celsius above average so far.

Across the world, all social systems will be stressed and adversely affected by climate change. Just one example: health. People will experience adverse health effects from high temperatures, water and food shortages, toxic algae in drinking water, increases in stress and mental health issues, particularly for populations who will need to leave their regions due to high temperatures, drought, or sea-level rises. Thousands, especially older people and children in cities, will succumb to heat waves. Mosquitoes and ticks will proliferate and likely cause disease migration including increasing outbreaks of dengue fever and malaria, some of the world’s most deadly diseases. Extreme weather events result in water source contamination and increased instances of waterborne diseases including cholera (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, 2016). These adverse health effects will lead to increased health care costs for governments and individuals, expenses that need to be considered when weighing the costs of investing in clean energy options to limit emissions. As Professor Richard Gammon once said, “If you think mitigated climate change is expensive, try unmitigated climate change.”

These terrifying scenarios have already begun. They will become far more common unless major changes to address global warming are rapidly undertaken across the globe. The current amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere as a result of human activity has already raised the Earth’s temperature by one degree Celsius. The “carbon budget” is how much more carbon (from oil, coal, natural gas) can be emitted and still have a likelihood of keeping global warming at 2 degrees Celsius. Some of the carbon humans emit is removed by carbon “sinks”—oceans (becoming more acidic) and forests (disappearing due to clear cutting, fires, and pests)—the rest goes into the atmosphere. The most recent research indicates that if we are to hold global warming to 2 degrees, 80 percent of known carbon reserves must not come out of the ground (McKibben, 2012; Clark, 2015).

The next two decades are absolutely critical to the future of the Earth hence the immediate need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Unfortunately, the general public, particularly in the United States, which leads the world in per capita emissions, still does not perceive climate change as a crisis. While public concern is growing about the need to address global warming, a Pew Research Center survey conducted in January, 2016 indicated that only 38 percent of the American people perceive climate change to be a priority issue needing to be addressed by Congress, ranking sixteenth in importance against all other issues (Pew Research Center, 2016). While 55 percent of Democrats ranked it as a priority, only 14 percent of Republicans listed climate change as a priority. Younger people are more concerned about climate change than the older people, with 52 percent of young adults indicating that climate change is a very serious problem compared to 38 percent of people 50 years and older.

Even though 97 percent of scientists confirm that climate change is caused by humans and predict with certainty that catastrophic consequences will occur if carbon emissions are not reduced immediately, a small number of powerful people, organizations, and corporations, who have much to lose from a change to alternative energy, have managed to dominate the public discourse and frame climate change as “debatable” and “controversial” (Oreskes & Conway, 2011). These few vested interests have been highly successful at influencing mainstream US media to spin the facts about climate change and create a false narrative. In a culture of immediate media spectacle, when the primary news providers are owned by transnational corporations, journalism becomes entertainment and profit, trumping social responsibility and full reporting of the facts (Sperry, Flerlage, & Papouchis, 2010).

Being able to critically question and understand the stories of our time is an important goal for all literacy teachers and the objective of this book. Throughout these pages we unpack the facts and stories about climate change with practical examples of how English teachers have fostered their students’ imagination and engaged them in powerful literacy lessons.

Recognizing the New Realities

There was a sense of urgency for the 196 nations attending the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris as scientists confirmed only 25–30 years are left to dramatically lower emissions to keep global warming to no more than 2 degrees Celsius. With the cooperation of President Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping an important and historic agreement to limit greenhouse gases and address global warming was reached.

Unfortunately, in many ways the Paris agreement is not enough. The agreement does not call for leaving carbon in the ground, which is essential. It did not establish a global carbon tax, though individual nations can impose one. All the pledges made in Paris were strictly “voluntary.” The richest countries, which have benefited the most from industrialization and put the most carbon in the air, provided only a pittance to address climate change in the poor countries. India, with 25 percent of its 1.3 billion people living in extreme poverty, is understandably reluctant to lessen energy production associated with economic growth. China, with its 1.4 billion people is in a similar situation, though both countries did make commitments. Even under the most optimistic assumptions, the pledges at best still set the world on a path to increasing global temperatures beyond 2 degrees.

So in the aftermath of the Paris agreement, and before the next climate summit in 2020, there remains a tremendous need for people the world over to understand the new realities and participate in the radical transitions necessary to avert the impending danger of climate change. Change is required in more than consumption habits. In our roles as workers and citizens we will need to transform energy, economics, transportation, agriculture, housing, media, health care, and community life. These are huge tasks that require creative actions by countless numbers committed to the cause. Who better to people this movement than students who see their future on the line. And who better to prepare these students than English teachers who understand the power of imagination to grasp big ideas and use literacy to change the world.

Indeed, climate change can be overwhelming. It involves thinking beyond what we already know and it goes against our natural tendency toward safety and normality. Global warming is incorrectly viewed as a topic for the distant future, not an urgent issue in the here and now. Being presented with the science of climate change does not mean everyone will accept its reality or start to do something about it. As students learn about climate change they may experience concern, doubt, anxiety, or ambivalence. Yet, their emotional responses can be starting points for developing hopeful and active engagement.

Our experience and that of the other English teachers we have been working with is that while students may come to the subject of climate change with doubts and questions, when they are able to inquire into the topic they become engaged, eager to educate others and address the problem.

Global warming is a topic that should and does matter to young people. A survey by the Yale Climate Change Communication Project found that the vast majority of parents (77 percent) support teaching climate change in schools (Adler, 2016). Yet, the education students do receive is limited. While 57 percent of teens understand that climate change is caused by human activities, only 27 percent say they have learned “a lot” about global warming in school (Leiserowitz, Smith, & Marlon, 2011...