![]()

1 | Public health, midwifery and government policy |

| HEATHER FINLAY |

Introduction | |

Background | |

The public health picture | |

Maternity inequalities | |

Organisation of public health | |

Prevention and integration: Overarching aims of the changes to the organisation and delivery of public health | |

Current policy and the role of midwifery in public health | |

Barriers to the implementation of public health policies | |

Barriers specifically around maternity services | |

References | |

INTRODUCTION

Public health [is] … the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organised efforts and informed choices of society, organisations, public and private, communities and individuals….

Wanless (2004, 3)

Midwifery care has always included a public health component, although the emphasis has shifted over the years from an emphasis on reducing maternal and child mortality and the control of contagious diseases at the turn of the twentieth century to a greater emphasis on increasing breastfeeding rates, tackling ‘lifestyle’ issues such as smoking and obesity and the need for good mental health by the beginning of the twenty-first century (Leap & Hunter 1993; Crabbe & Hemingway 2014). As a profession, midwifery acknowledges childbirth as a psychological and social event rather than a purely clinical event and that optimum outcomes are the result of individual, community and organisational effort. In essence midwives have understood that childbirth and raising a family are more than just a medical event and that the outcomes depend as much on the mother and the family’s social, psychological and environmental circumstances as on the input of health professionals.

This chapter will explore how the midwifery model interacts with government policy on public health. To do that, the chapter will start with a brief history of government policy around public health and midwifery. It will then go on to consider the social and economic background to government policy. Current government policy will then be explored in more detail and linked to the factors influencing the ability of midwifery to fulfil its public health role.

BACKGROUND

Through the early years of the twentieth century, midwifery became increasingly focused around institutions and the medicalised model of care, but this focus was starting to be questioned during the 1970s and 1980s with more proponents advocating the benefits of natural birth. The ‘natural birth movement’ resonated with a move towards a more holistic understanding of the causes of health and illness. The Health of the Nation policy document (Department of Health [DoH] 1992) acknowledged the need to promote health as well as to treat illness. This document has been criticised for its emphasis on the role of the individual in maintaining health while minimising the role of external influences; however, despite this, it signalled a belief in the importance of public health. In 1993, the ‘Changing Childbirth’ report emphasised the need to challenge the medicalisation of childbirth and design services around women and their families rather than institutions (DoH 1993). When the Labour government came to power in 1997, there was an increased recognition of the broader meaning of public health and an acceptance of the influence of disadvantage and inequality on health outcomes. The Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health (Acheson 1998) established a broad public health agenda that was followed through with Saving Lives: Our Healthier Nation (DoH 1999) and Tackling Health Inequalities: A Cross Cutting Review (DoH 2002). The public health role of the midwife was specifically mentioned in Making a Difference: Midwifery Action Plan (DoH 2001). Both Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier (DoH 2004a) and the National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services (DoH 2004b; referred to in the text as the NSF) placed midwifery care at the centre of the public health agenda. Both documents acknowledged that placing maternity care in a community context and actively engaging with disadvantaged communities can have positive consequences for the short- and long-term health of women and their children. This approach signalled the beginning of an organised effort to promote health and prevent disease both within communities and among individuals, with a focus (certainly within the NSF) on preventing inequalities even before birth. Thus, midwifery was placed as central to the execution of a broad concept of public health. The Sure Start programme (Department of Education and Employment [DfEE] 1998) and the subsequent Sure Start Children’s Centres (Department of Education and Skills [DfES] 2003) were created at a similar time, as part of the drive to improve outcomes for children and families and encourage multi-agency working (House of Commons: Children, Schools & Family Committee 2010). However, in 2010, the Labour government was replaced by a coalition government of Liberal Democrats and Conservatives. This change of government and the subsequent remodelling of the health services in England, alongside the social consequences of the economic crash of 2008, led to a public health environment that has some continuity with what has gone before but at the same time deep differences.

THE PUBLIC HEALTH PICTURE

Government policy from 2010 has been formulated against a background of a society in which obesity has become an increasing public health issue and there are continuing concerns around health inequalities. As a society, the United Kingdom in the early to mid-twenty-first century faces major health challenges, many of which have an impact on the public health role of the midwife. Obesity in both adults and children remains a challenge, and in the 20 years between 1993 and 2013, the number of obese men increased from 13% to 26% and the number of obese women increased from 16% to 24%, provoking fears that being overweight and obese is now becoming normal in the United Kingdom (DoH 2010; Health and Social Care information Centre (HSCIE 2015a). As would be expected, the trend for increased obesity in the general population is also found in women who are becoming pregnant, with an estimated one in five women going into pregnancy with a BMI of >30 kg/m2 (Soltani 2009 cited in Foster & Hirst 2014). The increase in obesity is taking place alongside large numbers of adults taking less than the recommended amount of exercise and not following dietary guidelines, especially around the ‘5 a day’ fruit and vegetable guidance (HSCIE 2015a). Although the number of smokers in the United Kingdom continues to decrease with only 24% of men and 17% of women smoking in 2013 (HSCIE 2014), there are still women who continue to smoke during pregnancy, with the latest figures showing 11% of women smoking at the time of their delivery (HSCIE 2015b). The common strand between obesity and smoking is that they are more common in some areas of the country and, more specifically, among some communities. For example, the percentage of women smoking in parts of the north-east of England is 19%, whereas in certain parts of London it is 5%. Similarly, the number of people who are obese is higher in the north of England and Scotland than the south (HSCIE 2015a). However regardless of where people live, we know that those who are in the lowest income quantiles are more likely to be obese and to smoke (HSCIE 2014). These statistics demonstrate that when it comes to healthy behaviours and health, there is inequality in those making healthy choices and in health outcomes, with those who are poorest and most vulnerable in our society at most risk of poor outcomes. The poor outcomes mean that those in the poorest areas can expect to die years earlier than those in the wealthiest areas and can further expect to have more years of life with ill health in their old age; this reflects a social gradient in health observed by Marmot (2010) whereby those who are poorest are at risk of worse outcomes. Recent figures suggest that women in the richest part of the country have 13 more disability-free years than women in the poorest parts of the country, and those in the wealthiest areas will live longer overall (NHS England 2013).

MATERNITY INEQUALITIES

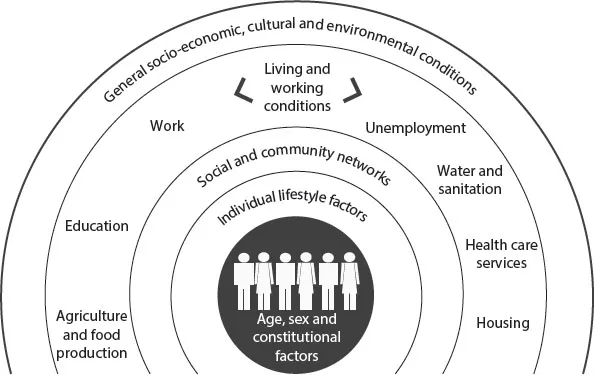

The inequalities in health are also apparent during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period. Although the rates of stillbirths and neonatal deaths continue to improve, there is a wide variation in risk across the United Kingdom. Alongside this regional variation in risk, those who lose their babies are more likely to be living in poverty, to be Black (or Black British) or Asian (or Asian British) (Knight et al. 2014). They are also more likely to be teenagers or aged over 40 (Manktelow et al. 2015). The recent confidential enquiry into maternal deaths also showed that the women who died were more likely to have come from deprived areas, to be older and to have been born outside the United Kingdom (Knight et al. 2014). The reasons why health inequalities persist, and the relative influence of the broader determinants of health is complex and outside the scope of this chapter (Benzeval et al. 2014). But it is becoming increasingly obvious that, at least in countries where there is easy access to health care, the health services around us are not a major influence on our chances of a long and healthy life. Other influences including environment, life chances, genetics and lifestyle are equally important (Public Health England [PHE], 2014a).

This section has highlighted two of the factors that have provided the background to the government policy around public health, namely the increase in obesity in the United Kingdom and the realisation that the persistence of health inequalities can only be tackled by an emphasis on the broader determinants of health. The next section will explore the organisational structures and approaches that are meant to make the difference.

Figure 1.1 The main determinants of health. (From Dahlgren, Goran & Margaret Whitehead. 1993. European strategies for tackling social inequities in health: Levelling up Part 2. http://www.euro.who.int/data/assets/pdf_file/0018/103824/E89384.pdf)

ACTIVITY

Before moving onto the next section, see Figure 1.1.

■ How could the factors identified in the different sections of the diagram influence your health?

■ How could they influence the health of the community in which you live?

ORGANISATION OF PUBLIC HEALTH

The organisation and delivery of health services in United Kingdom have been devolved since 1999, but the differences have become more marked since the changes to the organisation and delivery of health (including public health) in England since the 2012 Health and Social Care Act. This section will look at Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland first and then outline ...