![]()

p.1

1

KNOWLEDGE? WHAT KNOWLEDGE?

—Author Unknown

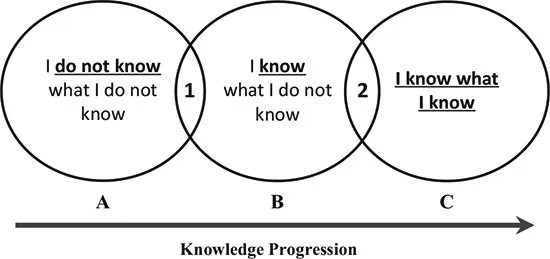

What is knowledge and why is it important? “Knowledge is power” and valuable knowledge, when used correctly, in a timely manner and at the appropriate level, can save lives in the battlefield or result in success in the business world. Consider the visual representation of “knowledge” in Figure 1.1 below. Please note that you can substitute “organization” for “I” here.

In Circle A, we find true ignorance. In this particular state for either an individual or an organization, there is no knowledge of what is unknown, and as such no questions can be asked or explorations undertaken. When we migrate to Circle B (as shown by the number 1) we have made a significant leap . . . we now know what we know and can therefore ask questions and explore and advance our knowledge. But let us be clear here, this is a choice and an action step. Many individuals and organizations stop here—they are comfortable in “knowing” what they do not know, but do not wish to pursue answers or knowledge or understanding. In Circle C the individual or organization has acted on what it has found out in Circle B and obtained knowledge—the organization or the individual now “knows” and has actionable and useful knowledge. According to futurists Talwar and Lazarova (undated),

p.2

(Item #40)

At this point we need to define what we mean by knowledge and knowledge management. What is knowledge and why is it important? Knowledge can be defined as what information, understanding or skill we gain from either experience or education. It is fundamentally an awareness of what is going on around us and our understanding of that situation. Knowledge has also been defined as the human faculty resulting from interpreted information; understanding that germinates from a combination of data, information, experience and individual interpretation. The Merriam-Webster dictionary defines knowledge as “the fact or condition of knowing something with familiarity gained through experience or association” and “ the circumstance or condition of apprehending truth or fact through reasoning: cognition” (Merriam-Webster.com, undated).

Knowledge management, on the other hand, are those strategies and processes designed to identify, capture, structure, value, leverage and share an organization’s (or individual’s) intellectual assets to enhance performance and competitiveness. It is based on two critical activities: (1) the capture and documentation of individual explicit and tacit knowledge, and (2) its dissemination within the organization (BusinessDictionary.com). Knowledge management has also been defined by Gupta and McDaniel (2002) as “the creative mining of information from diverse sources with the purpose of business opportunities in mind. As a firm works diligently toward perusing its information assets through the multitude of perceptual filters available, high-impact, matchless gems are unearthed, which have the potential to substantially affect the bottom-line” (p. 41). They make a useful distinction between knowledge management and information management noting that “the former implies a persistent, intentional effort of extracting from available information what is critical for business success, while the latter is more concerned with making critical information available in a timely and consistent manner to end-users within the organizational structure” (p. 41). Therefore, knowledge management is the deliberate and purposeful process of capturing valuable knowledge (intellectual capital) of people throughout the organization, making that knowledge available to people who need it (knowledge sharing/transfer), and then using that knowledge to create new knowledge (innovation) or use the knowledge to solve problems or make better decisions.

p.3

It is useful at this point to clarify the meaning of innovation and its links with knowledge management. According to Harkema and Browaeys (2002)

Parlby and Taylor (2000) are of the opinion that knowledge management is about supporting innovation, the generation of new ideas and the exploitation of the organization’s thinking power. Cavusgil et al. (2003) argue that knowledge management is a mechanism through which innovation complexity can be addressed. Knowledge management can manage new knowledge through the innovation process, as well as managing existing knowledge as a resource used as input to the innovation process. Perhaps the best way to understand the link between innovation and knowledge management is to recognize that innovation is a process that opens the opportunity for knowledge to be combined and recombined in new not previously thought ways (Du Plessis, 2007). This clearly links the need for knowledge management, knowledge transfer and innovation in organizations of the future. We would argue that skills in these three arenas are crucial for survival for every organization, large and small. A practical aspect of knowledge is what some term “knowledge sharing”. Knowledge sharing is the activity by which knowledge is exchanged among people and organizations. Knowledge sharing can be seen from the view of an individual seeking out knowledge (knowledge pull if you will) or when knowledge is “pushed” to members of the organization via various communication tools.

But let’s step back from definitions and look at a few famous examples throughout history that remind us of the huge value of knowledge. Military stories are especially important here because the stakes are so high, often involving life and death situations.

Example #1: British and French Battles over 100 Years

This example is drawn from (Luecke, 1993).

At the battle of Crecy (1346) the English used the longbow for the first time. This yielded a strategic and tactical advantage over the French as the longbow could send an arrow much further than existing bows of the time and could be reloaded much faster (a well-trained bowman could fire 10 arrows a minute). The British, under the leadership of King Edward III numbered approximately 12,000 (of which 7,000 were bowman) and faced 36,000 French soldiers (depending on the sources it could have been a bit larger or a bit smaller). The French made 14–16 charges against the British lines and the British archers fired approximately 500,000 arrows. The French suffered enormous losses (the numbers range from 12,000–30,000 depending on the source) and it was a stunning victory for the much smaller British Army from the use of “new” technology.

p.4

Note that in this particular example, the French were exposed to knowledge they did not have in the form of a long bow. They now knew what they did not know in Figure 1.1 above. But did they actually acquire this knowledge and use it?

Nearly 70 years later in 1415 at the battle of Agincourt, once again, a numerically smaller British Army (7,000 bowman and 1,500 other soldiers) was led by King Henry V. The English were outnumbered by 4:1. The results were exactly as with Crecy. The lowest estimate of French dead is 4,000 (with a high estimate of 11,000), while the British lost less than 150. The decisive factor in the English victory was, again, the use of the longbow.

It is unclear why the French did not apparently use the knowledge gained in 1346 from the lessons of Crecy and transfer that knowledge before the battle of Agincourt.

Our point is simple, but we believe powerful—knowledge that is “discovered” but not shared or transferred is not acted upon, and if not acted upon or transferred the result can be disastrous. In addition, knowledge that is not realized can inhibit future innovations. But let us turn our attention to a more modern example of knowledge management failures.

Example #2: Lessons Not Learned from World War I to World War II

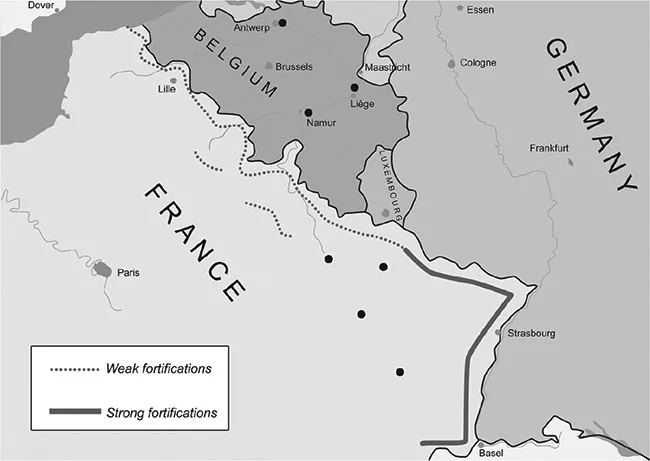

In the 1930s after many of France’s young men had been killed in WWI, France built a strong fortification that they called the “Maginot Line” (see strong fortification; solid line in Figure 1.2). This was a line of concrete fortifications, tank obstacles, artillery casemates, machine gun posts and other defenses. The commanders believed that the knowledge they had gained from the Word War I would be important to use in the pending second war with Germany.

These fortifications stretched from the Swiss border to the Ardennes Forest. The British and French thought that these Maginot fortifications would prevent the Germans from attacking through this line. Therefore, they moved the majority of their soldiers and equipment to the border of Luxemburg and Belgium (see weak fortifications; dotted line in Figure 1.2).

They assumed that the Germans would invade France through the Low Countries (Belgium and Luxembourg) as they had in 1914. However, the British and French could not move their troops into the Low Countries (Belgium and Holland) at that time because those countries were neutral. However, they planned that once the Germans attacked the Low Countries, the Allies would swing their armies like a gate through the Low Countries to prevent the Germans from entering France. The pivot point of this gate was the Ardennes forest at the northern tip of the Maginot line. The French assumed this forested area to be essentially impassable with modern heavy equipment and therefore, it was poorly protected. In May of 1940, just as the French expected, the Germans entered the Low Countries mirroring the Schlieffen plan of 1914 and the British and French swung their armies like a gate through Belgium to stop the German advance. Once the British and French did this, the German Army group entered the Ardennes forest, preceded by highly trained engineering battalions that cleared the way and promptly outflanked the Allied forces, making the Maginot line useless and trapping a large portion of the French Army and nearly all of the British expeditionary force between two Army groups and the sea (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_France). One source claimed that there were almost 2.3 million casualties with about 380,000 Allied Soldiers killed (http://5bloodiestbattlesofwwii.weebly.com/battle-of-france.html).

p.5

The Allied leaders used old knowledge and made assumptions based on this that proved to be fatal. What is interesting is that the German leaders similarly studied old knowledge, old strategies, and then, searched for new, innovative knowledge to give them a competitive advantage. In other words, the German leaders acted on “newly” developed knowledge and innovation. In this case, it was developing new ways to get equipment and troops through the Ardennes forest which the Allies believed to be impassable. We can infer that the culture of the Allied leaders created a type of “groupthink” mentality that led to their not testing “what they knew” to be true and therefore acting on incorrect or corrupt knowledge.

p.6

Fast forward to the winter of 1944. The Allies had just liberated much of France and were stretched thin because of their quick advance through the area. The Germans were in retreat and had suffered heavy casualties and were running out of fuel. Because it was winter, the roads were mud and ice, so the Allies assumed that the Germans were in no position to attack. The Allies had advanced quickly through France, and because of the bad weather conditions, the planes also had a hard time with aerial reconnaissance. The Germans massed a large striking force near the Ardennes and similar to what they did in 1940, moved through the Ardennes and attacked the American lines. The attack ...