Health Care Needs Assessment

The Epidemiologically Based Needs Assessment Review

- 172 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Health Care Needs Assessment

The Epidemiologically Based Needs Assessment Review

About this book

In the past 10 years spirituality and spiritual care have been much debated in professional healthcare literature, highlighting the need for a recognised definition of spiritual care to enable appropriate assessment of, and response to, spiritual issues. This accessible and highly relevant book surveys the numerous statements, guidelines and standards highlighted by these discussions, and equips healthcare professionals with the knowledge, skills and competence to provide the essence of spiritual care within their professional practice. Practical and evidence-based, this manual proves that delivery of good, professional spiritual care can build on intuitive human skills, and can be taught, learned, assessed and quantified. It gives readers the opportunity to move on from uncertainties about their role in the delivery of spiritual care by allowing them to asses and improve their understanding, skills and clinical practice in this area of care. Spiritual Care for Healthcare Professionals clearly grounds spiritual care in clinical practice. It is highly recommended for supporting academic study and encouraging healthcare practitioners to reflect on their practice and develop skills in spiritual assessment and care. Aimed at all healthcare professionals, it can be used by individual practitioners for continuing professional development as well as by academic staff developing educational programmes.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Accident and Emergency Departments

1 Summary

Introduction

- having fewer commissioning agencies and major provider units

- treating minor conditions in less specialized facilities or in general practice

- role-sharing between doctors and nurses

- the establishment of regional centres to deal with major trauma.

Structures

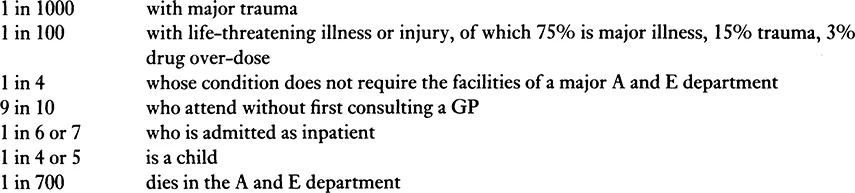

Incidence of conditions giving rise to demand

Activity

Effectiveness

Structures

- Size Some studies show that major units in small hospitals are equally effective, clinically, as those in large hospitals for a range of conditions. US studies indicate better outcomes for major trauma in larger hospitals, with less frequent procedural mistakes and fewer avoidable deaths.

- Observation wards These are reported to be associated with improved processes of care in the elderly and patients with head injuries.

- Dedicated operating departments Delays in surgical intervention can lead to poorer outcomes in cases of major trauma.

- Triage In emergency conditions, pre-hospital triage to appropriate expertise and facilities improves outcomes. In hospital, triage into patient categories (hospital doctor, nurse practitioner, GP) improves the processes of care. Triage into degrees of urgency results in a tendency to ‘over-triage’ into more urgent categories, so that fewer admissions are actually seen urgently.

Clinical management

- Major trauma

- Regional trauma systems based on regional trauma centres have been shown to be effective in the US trauma setting. Such a system was shown not to be more effective nor cost-effective in the one situation in the UK where it has been evaluated.

- Specialists needed on site. Secondary transfer of cases, especially of head injuries, is associated with poorer clinical outcome. If neurosurgery is not available on site there should be locally agreed guidelines for the rapid transfer of cases to the appropriate facilities.

- Trauma teams. Early mobilization of senior medical (A and E, anaesthetist, surgical specialists) and nursing staff, with rapid assessment and resuscitation improves outcome.

- Advanced trauma life support (ATLS). The value of having a casualty team trained in ATLS is widely accepted.

- CT scanning. This is effective in improving the management and outcome for head injuries. The value for other injured parts is less clear cut.

- Radiographic service. A 24-hour radiographic service with senior radiological assessment improves outcome.

- Minor trauma

- Nurse practitioners (NPs). There is no evidence from prospective randomized, controlled trials that NPs manage minor conditions as, or more effectively than junior doctors.

- Minor injury units (MIUs). There is no evidence about the effectiveness of MIUs in managing minor trauma relative to major A and E departments or the general medical services.

- Major illness

- Disease management protocols. The value of following protocols for major medical conditions such as acute asthma and severe chest pain is established and they should be adopted.

- Basic life support. This improves survival chances in emergencies.

- Minor illness

- On-site GP services in major departments. Patients with minor conditions are managed comparatively more appropriately using on-site GP services rather than traditional junior casualty officers.

- Polyclinics and extended primary care centres. The effectiveness of these arrangements for managing minor illness and injury compared with other arrangements is unknown.

Costs

Structures

- Size of department The average cost of a new attendance at an A and E department in England is about £45.00. The cost varies little and inconsistently among departments according to the annual number of new attendances.

- Amalgamation of units; full or partial closure of units No follow-up studies have been reported of the cost consequences to the health services. Whether or not hospital cost savings are achieved is not known. However when A and E department services are centralized additional costs fall on ambulance services and patients.

Clinical management

- Major trauma

- The additional cost of the first regionalized trauma system to be evaluated, including establishing and operating a regional trauma centre, was £0.5 million per annum. The cost consequences for contiguous A and E departments were small as the numbers of cases diverted were very small.

- Trauma teams, ATLS. Published data on the costs of these developments are not available.

- Major illness Data specific to the A and E department management of major illness are not available.

- Minor injury, minor illnesses The comparative costs of treating these conditions together with the other caseload in major A and E departments or of managing them in separate minor units are unknown. Where GPs are employed in major A and E departments to manage minor conditions there is a saving of more than one-third per case compared with management by doctors of senior house officer grade.

Cost-effectiveness

Models of care

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Contributing Authors

- Introduction

- Accident and Emergency Departments

- Appendix I National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Emergency Department Patient Record

- Appendix II Provider Minimum Data Set for A and E Departments with Computerized Systems

- References

- Index