1.1 Introduction

For most civil engineering problems, geotechnical engineering design starts by collecting detailed information on the soil strata at the site. A wide variety of site investigation techniques is used to collect information on the types of soil strata, their strength and stiffness properties, water content, topographical features of the site, and so on. In addition to this, the geotechnical engineers liaise with their structural engineering counterparts to obtain information on loading that will come on to the foundations and the allowable deformations that the structure can tolerate.

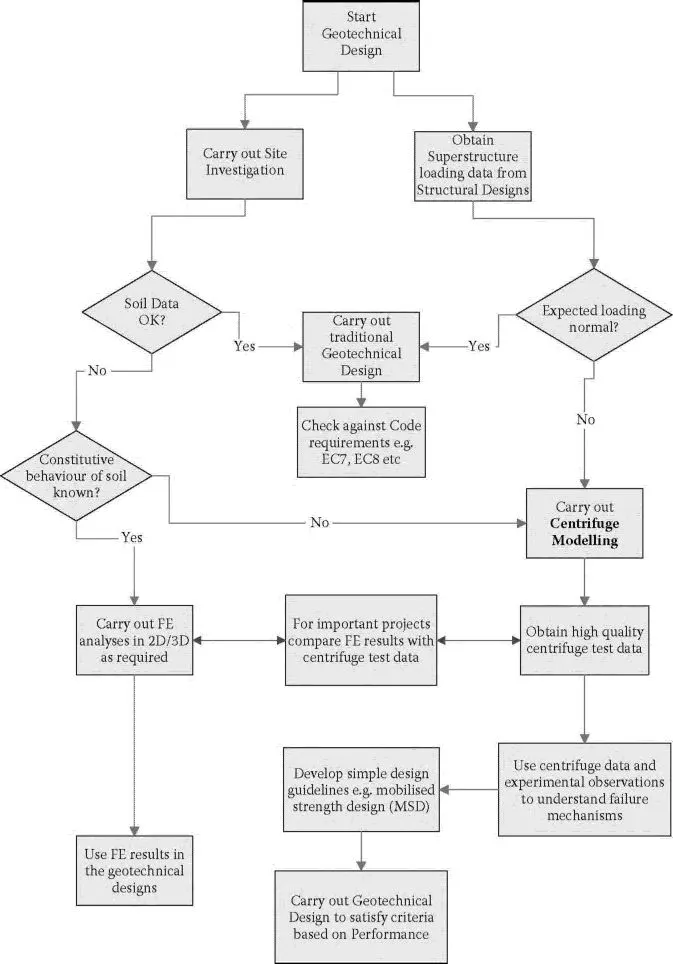

Using these two sets of information, a geotechnical engineer starts the foundation design. Of course, at the beginning of this process a choice of foundation types may be available. For example, for a normal building that has three or four floors, the superstructure loads can be carried by columns that are supported on individual pad foundations. Alternatively, a raft foundation may be considered. The ultimate choice of the type of foundation may depend on the in situ soil characteristics as well as allowable foundation settlements and/or rotations. This type of normal geotechnical design process may culminate by checking the solutions obtained against the relevant code requirements in existence such as Eurocode 7 (EC7) or Eurocode 8 (EC8), for example. A sim-plified flowchart for geotechnical design is presented in Figure 1.1.

Although the general procedure described above may be applicable to a vast majority of routine geotechnical designs, a significant number may require further analysis using some of the advanced methods. This may be required under a number of circumstances where the site investigations reveal poor soil conditions or when the expected loadings from the super-structure are abnormal. When the soil conditions are poor, if the soil behaviour is well researched and good constitutive models for the soil exist, finite element (FE) analyses can be carried out using well-established numerical codes. However, it is important that the constitutive models chosen for the soil are relevant for the type of loading. For example, certain soil mod-els may work well for monotonic loading but the actual loading from the superstructure may be cyclic in nature and the soil model’s performance under cyclic loading may not be known. Further, the parameters required by the constitutive models have to be determined from good quality soil testing carried out on undisturbed samples recovered from the site or by conducting in situ testing at the site, such as SPT or CPT testing.

Figure 1.1 Simplified flowchart for geotechnical design.

Now the question arises with regard to sites where the soil conditions are poor or unusual and there are no well-established constitutive models for those soils. Similarly the expected loading from the superstructure could be excessive or unusual. Under such circumstances centrifuge modelling can offer valuable insights into the foundation behaviour. The simplified flow-chart for geotechnical design outlined in Figure 1.1 identifies these routes that may require centrifuge modelling.

It is true that carrying out physical model testing in a geotechnical centri-fuge normally involves some amount of simplification of the actual field situ-ations. The main challenge in creating centrifuge models is in simplifying the field situation in such a way that the centrifuge model is able to capture the essential behaviour of the foundations. This aspect will be described in more detail in Section 4.3 in Chapter 4. In most cases, centrifuge modelling will give rise to data that reveals the essential behaviour and the failure mechanisms of the foundations that might occur. This information can be used to develop appropriate geotechnical designs. Similarly, competing geotechnical designs can be tested to compare their performances in a given soil type and for a given set of loading conditions. Also for important or particularly difficult projects it may be worthwhile to carry out simplified centrifuge model testing and use these experimental data to validate the predictions from a FE code. This process can be used to fine tune the FE analyses until the FE code is able to produce matching results to the centrifuge test data. Such a validated FE code can then be used to carry out analyses of complex geometries that are more common in the field. The finite element method is particularly well suited to handle complex geometries.

Centrifuge modelling has another important role to play. The data from centrifuge tests together with the observation of failure mechanisms made during centrifuge testing can be used to develop novel design guidelines for particular classes of problems. In fact, the contribution of centrifuge mod-elling to geotechnical design guidelines in this regard has been substantial over the years. This path is also identified in the flowchart in Figure 1.1.

1.2 Complex Role of Geotechnical Engineers

Adequate performance of foundations is of paramount importance if the superstructure is to perform as it is designed. The role of geotechnical engineers in any project is intertwined with that of structural engineers in almost all of the civil engineering projects.

1.2.1 Traditional safety factor-based design

It is common to base the geotechnical designs to withstand a given loading combination expected from the superstructure. This design philosophy relies on knowing the loads that are expected to be carried by the foundation and applying a suitable load factor for different load combinations.

Similarly, soil properties such as the peak and critical state friction angle, drained and undrained shear strength, and so on are known for the soil strata encountered at the site. Modern codes such as EC7 recommend par-tial factors to be applied to different soil parameters. The ultimate aim of the geotechnical designs carried out under this philosophy is to carry the loading imposed by the superstructure with an adequate safety factor. However, the actual displacements and/or rotations that occur under dif-ferent load combinations are not considered.

The geotechnical engineer’s role in this type of safety factor-based design methodology is well established. They have a linear interaction with structural colleagues in procuring the loading combinations expected from the superstructure and then carry out the geotechnical design using suitably factored soil strength parameters. This is quite straightforward in a majority of cases. The final design of the foundation is expected to carry the loads with an adequate factor of safety which is handed over to the structural engineers.

1.2.2 Performance-based design

In recent years the design philosophies employed in geotechnical engineering have changed rapidly and the concepts of performance-based design are being increasingly adopted. The role of geotechnical engineers will now involve estimating the deformations in the soil under the action of the applied load combination. This of course requires a good understanding of the soil stiffness as well as the soil strength. The settlements and/or rotations of the foundations caused by soil deformations govern the designs. There will be much closer collaboration with structural engineers in determining the allowable limits of the settlements and/or rotations by determining their effects on the superstructure. This type of interaction between the geotechnical and structural engineers is more iterative by its very nature.

The benefits of performance-based design are being realized in both geo-technical and structural fields. The final designs are well integrated, with both the behaviour of the foundation and its superstructure under a given loading being more predictable.

1.3 Role of Centrifuge Modelling

Centrifuge modelling has been identified as one of the possible methods that can help with geotechnical design when the soil conditions are dif-ficult, the constitutive models for the soil are not well defined or when the loading anticipated is unusual or extreme as shown in Figure 1.1. For these difficult or challenging cases, centrifuge modelling can have a role to play in helping the geotechnical engineer in both the design philosophies that are outlined above and are currently in use. In addition the centrifuge modelling of a class of problems such as retaining walls may be used to develop a new set of design guidelines by using the centrifuge test data and the physical observation of the failure mechanisms. This aspect has been utilised in a wide variety of boundary value problems at different centrifuge centers around the world.

1.3.1 Use of centrifuge modelling in safety factor-based designs

Let us consider a problem such as an offshore pile foundation being driven into stratified soils. The pile is anticipated to carry both axial and horizon-tal loads that vary with time depending on wave and wind loading on the superstructure. Let us assume that the constitutive models for the particu-lar types of soils are not known under cyclic loading. It is therefore decided to conduct centrifuge modelling to determine the size of piles required to support the loading.

This would be a relatively straightforward problem to be studied in a geotechnical centrifuge and, in fact, one that was investigated widely at many research centers around the world. In the centrifuge model, soil strata to represent the layered nature of the site in the field can be recreated, per-haps using the soil samples from the coring tubes used in the site investigation. Model piles of varying lengths and diameters can be inserted into the centrifuge model during flight, and can be tested to obtain their ultimate axial and lateral capacities. From this experimental data, a suitable pile section can be chosen in the geotechnical design to provide an adequate safety factor against the anticipated loads in the field.

1.3.2 Use of centrifuge modelling in performance-based designs

Performance-based designs in geotechnical engineering rely to a large extent on our ability to estimate deformations in the ground under the applied loading. It is usually acknowledged that such an estimation of ground deformations is in general more challenging than performing a safety fac-tor-based design using the concepts of ultimate limit state. The geotechni-cal engineering design becomes even more challenging when dealing with difficult soil conditions with unknown constitutive models and extreme or unusual loading from superstructure. However, these are the precise con-ditions under which centrifuge modelling becomes very useful and when performance-based designs are considered. The performance-based design concept allows for economic designs compared to safety factor-based designs by allowing some amount of ground deformation to be allowed. Centrifuge modelling can help geotechnical engineers determine the amount of ground deformation that will occur under a given loading, and also experiment to determine the limits of ground deformation beyond which the foundation may become unstable by developing a failure mechanism.

In addition to the direct use of centrifuge modelling to provide experimental data that can be used for geotechnical designs or in validating a particular design concept, the data from the centrifuge modelling can be used to develop a more fundamental understanding of the soil-structure interaction in a given problem. For example, Osman and Bolton (2004, 2006) have developed mobilised strength design (MSD) concepts with the primary aim of estimating soil strains and ground deformations that can be used in performance-based designs. Lam and Bolton (2009) applied the concepts of MSD to propped retaining walls based on their observations and experimental data obtained in a series of centrifuge tests. This is an example of the contribution and use of centrifuge modelling in helping develop design guidelines or procedures that can help geotechnical engi-neering practice. Again this pathway is identified in the simplified geotech-nical design flowchart shown in Figure 1.1.