![]()

1

How Big Is Small?

The innate human urge to create a better tomorrow has driven the world to continually innovate and compete. The last few decades have experienced the cross-fertilization of disciplines with the emergence of convergent technologies, which in due course have hatched and grown into novel knowledge-led businesses, one of them being nanotechnology.

The contours of the nanotechnology domain have been changing at amoebic frequency ever since its beginning. The science of “nano” (generally as small as 0.1 to 100 nm; 1 nm = 10−9 m) has already permeated all possible fields of applications with ideations inching their way into innovations for possible realization in the marketplace.

In 1959 in his talk titled, “There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom,” Professor Richard Feynman suggested the concept that “ultimately—in the great future—we can arrange the atoms the way we want; the very atoms, all the way down!” Such a thought of tailoring materials at will from the very basic building blocks was further christened as “nanotechnology” by Professor Norio Taniguchi in 1974: “’Nano-technology’ mainly consists of the processing, separation, consolidation, and deformation of materials by one atom or one molecule.”1

The inclusive nature of nanotechnology gives it a very special status as it mothers innovations to deliver inventions to provide a host of new, pure, and hybrid options by way of nanobiotechnology, nanostructures, nanocomposites, nanomedicine, nanotaggants for security systems, nanoelectronics, nanodevices, etc. This nano-inclusiveness creates the ecosystem to incite and integrate human talents and energy for global participation at all levels.

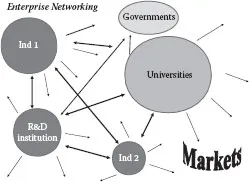

Such progressive developments are and will only be possible through dynamic global enterprise networking (Figure 1.1) of emerging and created markets, industry, academic institutions/universities, R&D organizations, and governments.

Academic institutions are wellsprings of knowledge with the goal of dynamically stimulating, fostering, and incubating minds. For successful enterprise and participative enterprise networking, one has to consciously guard against the dangers of academic institutions coalescing into “black holes of knowledge” with the inadvertent creation of virtual walls inhibiting meaningful knowledge transaction across academic boundaries into the demanding operational space.

For the sustenance of an innovative culture, academic institutions on one hand have to be involved in uninterrupted creation, enrichment, and maintenance of contextual educational programs with sustained knowledge renewal for the development of well-prepared human resources, and on the other hand participate in maximizing speedy transformation of knowledge into tangibles for industries to execute commercial exploitation.

FIGURE 1.1

Enterprise knowledge networking.

The industry sector has to link into the value-added knowledge networking as key irrigating channels for effective nurturing and productive harvesting of the knowledge-deliverables to the markets for societal benefit.

The process of “knowledge generation” and transfer demands innovative frameworks to justify ownership of the developed knowledge and benefit sharing between contributing partners, thereby providing pathways to incubation of minds to markets.

Governments are required to play a facilitating role in this dynamic enterprise, networking through enabling policies for the key actors to perform in an orchestrated manner to make the benefits of innovation finally available to the public.

De-cocooned enterprise networking demands tuning and retuning of intra- and interorganizational teamwork to craft and capitalize on opportunities without “reinventing the wheel,” with assured freedom to operate with minimized risk. Designing enabling conduits for innovation flow with the option to pole vault innovations from their centers of creation to markets now requires the strategic management of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) portfolios seamlessly built into the innovation process.

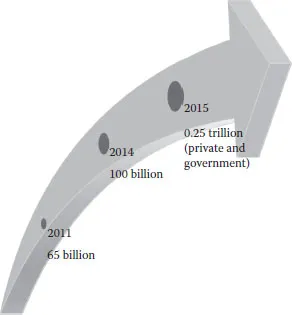

The promising potential of this field has set the governments around the world to continually invest approximately $10 billion per year with annual growth of 20% in the development of this field in all its diversity with the expectation to reap effective economic benefits for society in the near future. Joining the United States and European Commission Initiatives in Nanotechnology, the governments in the Asia Pacific Region have set up significant investments in nanotechnology since 2001. The Russian government also has taken up nanotechnology since 2007, which is being managed by the Russian Corporation of Nanotechnologies (RUSNANO).2 By the end of 2011, the total government funding for nanotechnology research worldwide was $65 billion, and expected to rise to $100 billion by 2014. Figure 1.2 shows the investment profile by governments in the field of nanotechnology.

The dominating investments are by the United States followed by Japan and the European Union (EU). Within the EU, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom lead public investments. China, Taipei, and South Korea have invested significantly in nanotechnology research over the past five years. The ratio of private to public funding for nanotechnology research in Japan, the United States, and the EU is 1.7, 1.2, and 0.5, respectively. By 2015, private and government funding is expected to be approximately $250 billion (Figure 1.2).

World Intellectual Property Report 2011,3 released in November 2011, states that the innovation process is increasingly international in nature and emphasizes that “innovation is seen to have become more collaborative and open…”. The report further states,

In particular, firms practicing open innovation strategically manage inflows and outflows of knowledge to accelerate internal innovation and to expand the markets for external uses of their intangible assets. “Horizontal” collaboration with similar firms is one important element of open innovation, but it also includes “vertical” cooperation with customers, suppliers, universities, research institutes and others.

FIGURE 1.2

Investment profile by governments in nanotechnology.

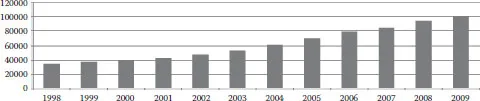

FIGURE 1.3

Total worldwide nanotechnology publications (Observatory NANO Factsheets, March 2011).

Knowledge sharing and peer group recognition is a key incentive among knowledge seekers and research publications in all forms continue to be the lead venting mechanism. Since the conceptualization of “nano,” the scientific community has been on the Formula One track “Nanoathon” racing ahead with new findings, which is evident from the number of publications involving the science of nano depicted in Figure 1.3.

An Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report4 indicates 63% of the global nanotechnology-related publications are contributed by the United States, Japan, Germany, France, United Kingdom, and China. Interestingly, Japan, China, Germany, France, Korea, Russian Federation, India, Taipei, Poland, Brazil, and Singapore have higher shares of nanotechnology publications relative to that of all publications from those countries, showing that nanotechnology has become a major thrust area for R&D. In contrast, countries such as the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia have higher shares of all publications relative to that of nanotechnology publications, even though nanotechnology is a major thrust area supported by the respective governments. The OECD report also presents an analysis in terms of the highly cited publications in the nanotechnology area in which the United States significantly stands out as compared to publications from the other countries. Performance of countries such as Japan, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom follows, but is substantially lower than the United States. However, China is fast catching up with the leading nations in the quality of its publications and citations in science and technology (S&T) journals. Nonlinear evolution of the frontiers of nanoscience and nanotechnologies has been due to the blurring of disciplinary boundaries and creation of convergent technologies as is well illustrated in the contents of the scientific publications (Figure 1.4) in which the fields that converge are typically material science, metallurgy, chemistry, physics of condensed matter, polymer science, electrical engineering, electronics, instrumentation, and biology. New fields, such as plasmonics, metamaterials, spintronics, graphene, cancer detection and treatment, drug delivery, synthetic biology, neuromorphic engineering, and quantum information systems, also have sprouted up in recent times. The last decade has witnessed as well the growth of international S&T networks and intergovernmental cooperative programs in nanotechnologies.

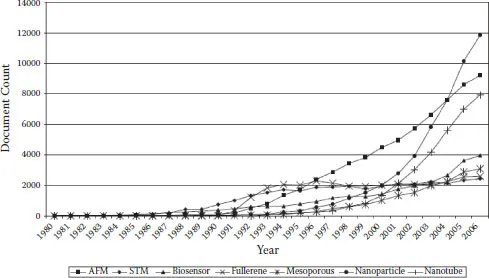

FIGURE 1.4

Number of publications in selected fields of nanotechnology. (From Finardi, U., Time-space analysis of scienti...