1

Information Technology’s dark side

IT-related Overload and IT Addiction

Charles Darwin (1871)– a naturalist best known for his contributions to the science of evolution– wrote, “It has often been said that no animal uses any tool” (p. 51). Darwin challenged this 19th-century statement through his own observations and those of his colleagues. For example, Darwin noted that Asian elephants would repel flies by waving a branch in their trunks. Interestingly, the elephants would first fashion the branch into a tool by removing side branches or shortening the stem. Earlier, Savage and Wyman (1843–1844) reported that chimpanzees in their natural habitat use stones to crack fruits. They also devise sticks for hunting prosimians. Later, Köhler (1917/1925) observed that big apes restructure their environment to reach food. Thus, wild animals adapt tools to make them more efficient and use them to enhance their chances of survival. It is indeed more efficient for the elephant to have the right tool for chasing flies away than relying on the length of his trunk. Yet, animals do not exhibit the full scope of intelligence observable in humans. Evolutionary research has related the use of tools with the development of hominid brains (Wrangham, 1994; Carvalho, Cunha, Sousa, & Matsuzawa, 2008; Sanz & Morgan, 2013). Our early hominid ancestors, such as Ardipithecus, were capable of making simple tools (Panger, Brooks, Richmond, & Wood, 2002; Roche, Blumenschine, & Shea, 2009). Neanderthals displayed their abilities in handling complex Paleolithic tools for their survival. Through evolution, the better early hominids designed and handled complex tools, the smarter and fitter they became. Early hominid’s use of tools, like ours today, was goal-driven and made it possible to accumulate exogenous resources and conserve endogenous ones.

Misused tools or valuable resources?

Like humans, tools have evolved over time. They provide capabilities that undoubtedly were never imagined by our early ancestors. However, in our digital age, the design and use of ‘digital tools’ such as the smartphone is causing some concern. The popular press is full of revelations of this First World problem. For example, Tristan Harris, a former product manager and design ethicist at Google, recently declared war on smartphones. He stated in an interview with Rachel Metz for the MIT Technology Review:

It’s so invisible what we’re doing to ourselves.… It’s like a public health crisis. It’s like cigarettes, except because we’re given so many benefits, people can’t actually see and admit the erosion of human thought that’s occurring at the same time.

(Cited in Metz, 2017)

Research has demonstrated that even the absence of a smartphone in one’s pocket can be a cause for concern. Specifically, phone owners have been reporting ‘phantom vibration syndrome’. In this syndrome, the phone owner is so used to receiving messages that her body perceives that the phone is vibrating and delivering information even when it is not (Drouin, Kaiser, & Miller, 2012). Nicholas Carr (2017), in his article “How Smartphones Hijack Our Minds”, reported research denouncing the addictive nature of the smartphone and its weakening effect on the brain. People are becoming too dependent on their smartphone, and their ability to think and make sound judgements is decreasing. Carr concluded from his readings that when a smartphone’s proximity increases, brainpower decreases. In a similar vein, Hancock (2014) now muses over whether current technology engenders stupidity instead of whether it can cure stupidity.

The smartphone is not the only Information Technology (IT) that has a dark side. The popular press is full of accounts about the dark side of other types of IT: information overload, email fatigue, iDisorders, technostress, or social media junkies to name just a few. Though clearly these advanced technologies have many wonderful uses, their dire consequences on users’ behaviour and stress is generating societal concern. However, IT itself is not the problem. Rather it is how IT is actually used that can lead to good or dire consequences. When it is not used well, the dark side of IT is unveiled.

We are particularly concerned with two ‘dark side’ challenges: IT-related overload and IT addiction. We define IT-related overload as the state of being challenged in processing information used in IT-related activities. Rather than focus on the amount (i.e., input) or symptoms (i.e., output) of overload, we seek to unlock the black box of the mind and focus on mental processes. That is, we are concerned with a form of brain overload, or the inability to adequately process input and handle the associated brain load. We define brain load as the emotional and cognitive efforts required by individuals to appraise and process inputs using the resources available to them. Further, we define IT addiction as the state of being challenged in balancing IT usage mindfully so as to preserve one’s resources.

When used well, we view Information Technologies as powerful tools. In particular, we view them as exogenous resources – digital tools that may require our endogenous brain resources. Resources are defined as “objects, personal characteristics, conditions and energies that are valued by individuals or that serve as a means of attainment of other resources” (Hobfoll, 1989, p.516). They may be endogenous physical, emotional, or cognitive energy (Hobfoll & Freedy, 1993). Some are temporal. The resources affect each other, exist as a resource pool (Kahneman, 1973), and are necessary for cognitive processing (Monetta & Joanette, 2003). Both endogenous and exogenous resources are necessary to battle the dark side of IT.

Brain overload

The dark side of IT has exponentially increased in the last half-century as a result of the introduction of new digital tools such as the Internet, email, smartphones, and Social Networking Systems (SNSs). Indeed, since the commercialization of the Internet skyrocketed shortly after the introduction of web browsers, we find ourselves increasingly inundated with information in the form of requests, advertising, pop-ups, new apps, emails, or text messages delivered by various technologies. We are deluged with information that is continuously being pushed at us by others or pulled by us from the Internet and other myriad of technologies because we feel compelled to seek additional information or social contact. We face the challenge of dealing with the huge amount of information that is omnipresent in our world. “Never in history has the human brain been asked to track so many data points” (Hallowell, 2005, p.58). The consequences are serious in today’s information-rich environment. In First World countries, “contemporary society suffers from information constipation. The steps from information to knowledge and from knowledge to wisdom, and thence to insight and understanding, are held captive to the nominal insufficiency of processing capacity” (Hancock, 2014, p.450). Managers and employees who suffer cognitively from overload may end up making an increasing number of errors and poor decisions while trying to process dizzying amounts of data (Hallowell, 2005). They may also suffer emotionally from the overload, IT addiction, and workplace stress. For example, employees working in high-technology industries have been found to demonstrate psychosomatic symptoms and reduced productivity related to high mental demands (Arnetz & Wiholm, 1997; Tarafdar, Tu, Ragu-Nathan, & Ragu-Nathan, 2007). One estimate places the cost of information overload due to “lowered productivity and throttled innovation” at $900 billion a year (Powers, 2010, p.62).

We believe that ‘brain overload’ is a better term to describe the phenomenon more commonly called ‘information overload’. Processing the information that Information Technologies deliver is brain-related and heavily reliant upon available resources. Therefore, brain overload is a function of the brain (e.g., processor) and not information (e.g., input). While the consequences of brain overload have been reported frequently in the literature, they systematically have been attributed to situations characterized by too much data, information, or connectivity. The focus has been on the input and the output rather than on the cognitive processes (i.e., black box).

More than four decades ago, Simon (1971) pointed out the challenges of processing so much information and the need for attention resources to do so. He wrote,

What information consumes is rather obvious: it consumes the attention of its recipients. Hence a wealth of information creates a poverty of attention and a need to allocate that attention efficiently among the overabundance of information sources that may consume it.

(Simon, 1971, pp.40–41)

Indeed, there has always been a lot of data in the world. Not many of us have read all the books in a library. Libraries are not blamed for causing information overload – technologies, especially email, are.

Using resources mindfully

Recently, this automatic email reply arrived in one of our inboxes:

Hi there, Thanks for your mail, which I regrettably will not read since I’m working away from the office. I’ll be back, however, on the 4th of May fully charged. So if your email is still relevant after then, please send it again or otherwise it’ll end up in the heap of mails that I’ll unlikely respond to. Even better, if the matter is urgent, give me a call at +XXXXXXX. Have a good one – Corey

PS – join the fight against email fatigue and let others know that email, while helpful, shouldn’t be a substitute for face-to-face or telephone communication. Together, we can make the world a less stressful place.

In the digital workplace, managers show signs of overload from communications delivered by email and other technologies. Some respond as Corey does in the email signature above. In fact, Corey is sharing his coping strategy for curbing email overload in this automatic reply. Consequently, he is using the auto-reply option in a mindful way, sparing his resources. Research from psychology supports the idea that processing all inputs such as incoming email messages involves a certain level of resources. Expending endogenous resources can reduce an individual’s brain load and increase his processing efficiency. In addition to each individual’s endogenous pool of resources are exogenous ones. Time is a common exogenous resource that all too often proves inadequate. Indeed, Corey is apparently lacking enough time to read all the emails in his inbox upon his return to the office. He warns email senders that their message simply may not be read unless it is re-sent at a later time. Also, Corey kindly urges the senders to question the relevance of the content of their messages over time. He is expertly building healthy boundaries for handling a flood of emails. In other words, he is ensuring that he has adequate resources for solving his IT-related overload equation. He does provide the option of giving him a phone call or meeting him face-to-face.

Not everyone is afraid of brain overload in today’s digital world. In fact, some people enjoy it and impatiently wait for the next tweet or text. They appreciate the high-speed connections that allow them to leverage a vast range of information in accomplishing a phenomenal amount of work. Slow connections leave them bored and annoyed. These individuals might even suffer from a form of IT addiction that compels them to stay connected for fear of losing out.

To better understand the role of the brain in processing information, we propose a model based on cognitive theories of memory (Atkinson & Shiffrin, 1968; Bower, 1981). In particular, we draw on both the emotional and cognitive aspects of the brain and consider the resources necessary to fuel its processing of inputs. We introduce our model, the Emotional-Cognitive Overload Model (ECOM), using the metaphor of a blender.

Blender metaphor

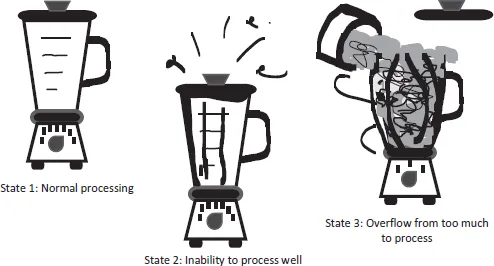

We use the commonplace blender to explain the brain overload phenomenon. With a blender, we normally pour in the ingredients that need to be processed and push the button to mix/blend. This is State 1 in Figure 1.1. If the ingredients are hard to blend or if we want a smoother consistency of blended materials, we turn the knob to liquefy rather than blend. That is, we call on the blender’s greater processing capabilities. For simplicity sake, we assume that processing abilities are similar for most blenders. State 2 in Figure 1.1 is when the blender cannot handle the processing. Finally, if there are too many ingredients for one batch in the blender, we can blend some of them, pour that into a separate container, and then process the remainder in another batch. If we do not process in batches, there will be an overflow condition, which is what is happening in State 3 in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1 The blender approach to understanding overload

The material to be processed represents information, and the blender is used to represent the brain’s memory processes. Even though we only have one brain, it is organized in a way that allows us to process input in batches. In State 1 the information to be processed is limited enough or easy enough that it can be processed without difficulty. Consequently, no overload occurs. However, in State 2 the person’s pool of resources is inadequate for processing the information. The person may lack expertise in processing the information, lack interest in or time for solving the problem, or be too exhausted because of a lack of physiological resources. As a result, the person must either call upon a higher level of cognitive ability than usual to be able to process the information or adapt to lower levels of performance by learning to live with an increased number of errors, reduced information integration, and impaired decision-making (Bettman, Johnson, & Payne, 1990; Shiv & Fedorikhin, 1999). Of course, while blenders may be relatively similar in their processing abilities, they may vary slightly in terms of power or capacity. Individuals, on the other hand, definitely have very different cognitive abilities and stored memories in the brain that are used to process information. More precisely, they may each have a very different pool of resources from which to draw. We suggest that some individuals process information better than others. They have better cognitive abilities. In State 3, the information processing needs to be made more efficient. One way to do this is to chunk the information, which is like processing the information in batches. However, at some point, the amount of information or the ability to process it exceeds an individual’s resources. This leads to a state of emotional and cognitive overload.

What we have not addressed so far is when to start the blender. We argue that there must be some relevant (pertinent) input that starts the blending process – such as the desire to have a fruit smoothie or a frozen daiquiri. It is unlikely that an individual would start the blending process if the request is to blend cod liver oil with jello, or some other ghastly concoction. Similarly, before an individual starts processing information, there must be some pertinent input to motivate the processing and it must be perceived positively. In our blender example, the individual can remember how good the smoothie or frozen daiquiri tasted in the past and is motivated by this positive memory. Furthermore, the smoothies this person so enjoys making and drinking may be loaded with sugars or alcohol, consumption of which is addictive to the brain. This addiction may also motivate the person to start the blender.

Clearly our blender metaphor is quite simplistic when it comes to explaining overload and viewing smoothies as a form of addiction. We hope to remedy this with a more complex model presented in Chapter 3, following a discussion of models in Chapter 2. In the ECOM, Emotional-Cognitive Overload (ECO) is defined as the negative emotional and cognitive consequences of brain overload. In Table 1.1 we continue our blender metaphor by highlighting key aspects of information processing that are an important part of the ECOM but which are not usually elaborated upon in overload research.

TABLE 1.1 Comparison of brain overload in blenders and people

| Aspects of information processing | Blender state | Person state |

| Pertinent input | We will not turn the blender on unless we want to concoct something tasty, like a smoothie with brain-rewarding sugar. | The information will not be processed unless it is perceived to be pertinent. In information processing, the valence may be positive or negative. When information is extremely pertinent, the person may exhaust all resources to process the information. |

| Processing | No overflow. The container can hold all of the ingredients and process them. The blender may be used seldom or never. | No overload. The person can process all of the information perceived as pertinent. If the individual’s resources are not used fully, the person may be underloaded, or bored, and may decide to use resources for other activities. |

| Individual differences | The blender can do different types of blending. Some blending is very coarse. If the material is to be smoother, a higher level of processing is needed. The knob can be turned to a different position indicating more ... |