- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

With the introduction of yearly appraisals and revalidation every general practitioner needs to be armed with a good Personal Development Plan. This book provides the information needed to create just that. Guiding the reader through the consultation looking for Patient's Unmet Needs (PUNs) and the Doctor's Educational Needs (DENs), it focuses on those learning needs that help to provide competent care for patients. All general practitioners will find this book a straightforward, no nonsense, practical approach to help them incorporate their learning needs into the realities of everyday practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access PUNs and DENs by Richard Eve in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Why bother with learning?

Competence

My reason for learning is so that I can become and remain a good or ‘good enough’ doctor. I want to be confident, reflective and fulfilled, and enjoy what I do. This is my motivation for learning. I am not driven to learn by demands from outside agencies such as the General Medical Council or primary care trust. So what makes a good doctor? It is not that difficult to define, but it is very difficult to measure. I need to know what skills make a good doctor so that I can focus my own learning and development appropriately. And which skills are the most important ones, that should take most of my time?

Several skills are listed below. Put the four most important ones on the left and the less important ones on the right.

Empathy and sensitivity

Audit skills

Communication skills

Clinical knowledge

Drug budget management

Conceptual thinking

Protocol design skills

Health promotion skills

Audit skills

Communication skills

Clinical knowledge

Drug budget management

Conceptual thinking

Protocol design skills

Health promotion skills

How did you get on? It is frightening that we seem to be spending what little time that we have for learning on drug budgets, audits, protocols and health promotion. Important as these may be, we must continually upgrade and hone the more important skills first.

Who should we ask to define competence in a doctor? Should we ask our patients, the general public, politicians, the Royal College of General Practitioners, the General Medical Council or perhaps our fellow GPs?

A group of occupational psychologists have made an effective stab at defining what makes a good doctor. They asked a large number of GPs to name a GP who they would be happy to recommend to a friend or to have care for their own family (i.e. they asked someone ‘in the know’, but from a patient’s perspective). They selected those GPs who were most commonly mentioned and put them into three groups. The GPs had to bring with them one example of an incident that they thought represented excellent general practice and one that represented poor general practice – that is, real events that had occurred in general practice. A system was used to identify common themes. The outcome was that 14 different aspects of competency were defined. Thirty-five respected working GPs were facilitated in discovering how to break down and identify the constituents that make a good doctor.

The 14 competencies were as follows:

• empathy and sensitivity

• personal organisation and administrative skills

• communication skills

• personal attributes

• conceptual thinking

• personal development

• managing others

• team involvement

• stress coping mechanisms

• legal, ethical and political awareness

• professional integrity

• job’s relationship to society and family

• clinical knowledge

• learning and development.

The language that was used to describe these competencies was encouraging. Phrases included the following: able to compromise . . . showing sensitivity to colleagues . . . knowing when to delegate . . . being aware of own limitations . . . having an interest outside medicine . . . having humility and empathy . . . learning to say sorry and control one’s anger . . . integrity, flexibility, unselfish, innovative, motivated . . . taking responsibility . . . able to judge what is important . . . respect for those whom society does not like . . . keeping up with current practice . . . a skilled negotiator . . . a good facilitator . . . a team player . . . willing and able to learn from experience.

This work was later combined with two other methods of assessing competence, namely studying video consultations and asking patients, and the final outcome was published in Patterson F, Ferguson E, Lane P et al. (2000) A competency model for general practice: implications for selection, training and development. Br J Gen Pract. 50: 188–93.

Clearly, measuring competence is a little more complicated than looking at your beclomethasone/salbutamol prescribing ratio! If you want to ask your colleagues how they judge your competence and see your strengths and weaknesses, I have described a system that we have used in our practice in Appendix 2. If you want to find out what your patients think of your competence, then the address to write to in order to obtain a well-tested and tried system is given in Appendix 1.

Measuring competence is complicated.

Competent doctors apply evidence-based medicine (EBM). Is the best doctor the one who has got the highest number of heart failure patients on to ACE inhibitors?

Rate the competence of the following doctors.

• Doctor A. Identifies and recalls all patients with heart failure. The computer search reveals that he has achieved his standard of 80% of such patients being started on an ACE inhibitor (compliance rates and later treatment withdrawals not recorded).

• Doctor B. Is desperate to stay within her prescribing budget. If she goes over budget, the in-house physiotherapy service will be withdrawn and her patients will suffer as a result. She cannot possibly prescribe more ACE inhibitors and remain within budget. She knows the evidence but chooses to ignore it.

• Doctor C. Has no direct access to echocardiography facilities. It takes at least six months to see a cardiologist. Personal experience causes him to believe that up to a quarter of heart failure patients will not tolerate effective doses. He feels that if he is to prescribe safely he needs to offer regular follow-up in order to check blood pressure and renal function and to titrate up to the maximum tolerated dose. He feels uncomfortable launching such a programme without the support of secondary care, and since they seem to be overloaded already, and he is busy enough as it is, he elects to postpone the introduction of an ACE-inhibitor-prescribing policy.

• Doctor D. Having been made aware of the evidence, she opportunistically reviews her patients when they attend, concentrating only on those who were already on diuretics for presumed heart failure. She takes into consideration compliance, contraindications, the ease with which the patient could attend the surgery and the patient’s health philosophy. She is aware of her own over-cautious approach to drugs (and her drug budget), but tries not to let it influence her prescribing. A year after starting her programme a computer search shows that only 30% of her heart failure patients are on ACE inhibitors.

• Doctor E. Is very busy organising his colonic cancer screening programme and providing a GP endoscopy service. He has little interest in cardiology and has never heard of the evidence about ACE inhibitors. He continues to practice uninfluenced by this evidence.

What outcome measure will tell you about the competence of these doctors? Prescribing statistics will tell us little. Evidence-based medicine only offers statistical significance relating to cost-effective interventions on ‘freak’ populations. The good general practitioner assesses its relevance to their own practice population and then translates it into personal significance for individuals in the consultation. In order to do this effectively, a doctor will need attributes in all 14 competencies. Make a start by conducting a self-assessment of the 14 competencies. Politicians are going to need to know that competence cannot be judged on the basis of simple outcome measures alone.

Accountability

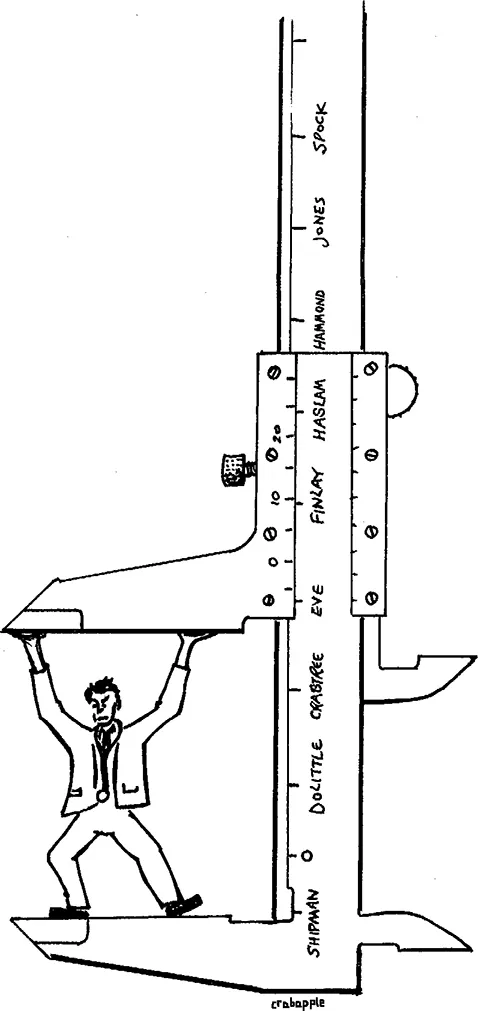

Whenever I have come across a patient satisfaction survey, the results have always shown that patients were happy with the service they received and that they had confidence in their GP. Following the Shipman case, the Bristol paediatric cardiology inquiry and the case of a rogue gynaecologist, politicians and the media have expounded the need for the public to be reassured about the competence of doctors. The NHS Executive, Royal College of General Practitioners, General

Practitioners Committee and General Medical Council have had a field day commissioning reports, playing politics, arguing, releasing press reports and setting up committees. So far they have managed to worry the public and make GPs feel threatened and vulnerable. Clinical governance is now well established, and yearly appraisals and revalidation are upon us. Well, don’t worry – get your priorities right and all will fall into place.

Place the following in order of priority when it comes to being accountable.

Primary care team

Government

Self

General Medical Council

Primary care trust

Partners

Family and life outside general practice

Patients

Government

Self

General Medical Council

Primary care trust

Partners

Family and life outside general practice

Patients

I expect that your answers are pretty similar to my own.

Self

Before anything else, you are accountable to yourself. By definition, a professional is someone who is accountable to himor herself for maintaining competence. Every day doctors make decisions and judgements in the privacy of the consultation. If a doctor loses the inner drive to ‘do a good job’, then no amount of outside accountability will correct the problem. So it is important to be reflective about your work, think about what you need to stay competent and enthusiastic, and base your learning on your own fulfilment and not on pleasing others.

Family and life outside general practice

Workaholics seldom stay the course. It is vital to programme time for other things, whether they be personal relationships, children, hobbies or other intellectual pursuits. Many young doctors now follow ‘portfolio careers’. When you are on your deathbed, do you think your last words will be ‘I wish that I had spent more time at the surgery’?

Partners

Dysfunctional partnerships are not uncommon. You are the directors of a small business that is providing care to the same community. How can you do a good job if you are all pulling in different directions? The arguments for a salaried service are gaining strength, but the reality is that most of us are in partnerships and we are accountable to each other. What a recipe! Put together a group of men and women of different ages and backgrounds, with different aspirations and values, and at different stages in their lives, and expect them just to get along fine! In fact, this is a classic example of turning a threat into an opportunity. All of those differences can be turned into a great strength, but not without effort. You will need tolerance and listening skills, you will need to dedicate time to teambuilding, and you will need to discover each other’s strengths and learn how the practice can use them. Facilitated ‘away-days’ can help enormously here.

Primary care team

So you are looking after yourself – you have a reflective, competent, balanced life – and the effort put into achieving a united partnership is paying off. You are nearly there now. We work with a host of other professionals, and primary care is now truly multidisciplinary. We now have an enormous and disparate group that has to work effectively as a team. If the partnership is dysfunctional, what hope is there for the wider team? Nevertheless, we must accept that we are accountable to the whole team, every member of which has aspirations, learning needs and problems that need to be addressed. We used to have primary care team meetings (what a bun-fight!) with 30 or 40 people talking in little groups all at the same time. They didn’t last long. A primary care team actually consists of a complex relationship of groups, subgroups, inner groups, loose-knit groups, communication structures and networks. For such an organisation to run efficiently, it needs quality management. I may have a role as a director, but the co-ordination and communication structures are the responsibility of my practice manager. It is a time-consuming job that requires special skills, and by delegating to effective management I am recognising my accountability to the team as a whole.

Patients

Doctors have always been accountable to their patients, if only to protect their reputation. However, accountability is no longer held only on an individual basis, but is now also for the health status of populations. You must address issues not only of empathy, sensitivity, communication skills and clinical knowledge, but also of audit, benchmarking and public health issues. The involvement of patients in the assessment and delivery of care is something that we can expect to see much more of in the future.

The profession

The General Medical Council is no longer limited to removing rogues and the grossly incompetent, and it now wants a bigger slice of the action. The GMC want to play a role in raising standards generally, and believes that revalidation will achieve this.

Primary care trust

You may have grown accustomed to demonstrating some accountability to the health authority with practice reports, referral and prescribing data, but primary care trusts (PCTs) are taking this a step further with clinical governance. Some PCTs may take the enlightened route and view clinical governance as an opportunity to facilitate and support you in your personal endeavours to be a good doctor who is accountable to yourself, your practice and your patients. Other PCTs may take the other route and bombard you with targets, protocols, guidelines...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- About this book

- About the author

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Why bother with learning?

- 2 Finding time for learning

- 3 Discovering learning needs with PUNs and DENs

- 4 Examples of reflective learning

- 5 Research to reality

- 6 Sharing PUNs and DENs

- 7 From PUNs and DENs to PDPs

- Appendix 1 Discovering learning needs by asking patients

- Appendix 2 Discovering learning needs by asking colleagues

- Appendix 3 PUNs summary and logbook

- Index