![]()

Training—The act, process, or method of one that trains; the skill, knowledge, or experience acquired by one that trains.

Law Enforcement—The generic name for the activities of the agencies responsible for maintaining public order and enforcing the law, particularly the activities of prevention, detection, and investigation of crime and the apprehension of criminals.

Law Enforcement Officer—An employee of a law enforcement agency who is an officer sworn to carry out law enforcement duties. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary)

The first known use of the word training can be traced back to 1548. However, the Spartan and Roman Empires were known for their strict and harsh training regimes before 1548. The first recognized training of law enforcement officers in the United States was not until the early 1900s, stemming from widespread corruption in police departments (Chappell 2008). In fact, the first recognized formalized training for police officers was started in Berkeley, California, in 1908, soon followed by the New York City police academy in 1909 (Bopp and Schultz 1972). However, there is some evidence that New York City had some police training going back to 1853 (Palmiotto 2003). The police were quick to adapt a military model of training owing to familiarity to the model, a behaviorist method of learning. In 2006, the Bureau of Justice Statistics reported a total of 648 law enforcement training academies nationwide that trained approximately 57,000 recruits annually.

Training has evolved during the last century of law enforcement. Law enforcement training still has many facets of the basics but now has elements of more sophistication. Law enforcement training has changed from just providing basic recruit training to advanced training involving computer forensics and other forms of technology. Also, there has been an expansion of training methods now being incorporated into law enforcement training. Further, law enforcement training academies have grown to where there are some academies that have a 30-week basic training course, and yet, almost on a daily basis, law enforcement officers find themselves in trouble regarding the way they conduct their business. Avoidable failures continue in almost every realm of law enforcement. The reason is quite simple: the volume of complexity of knowledge today has exceeded our ability as providers of training to properly deliver to the officers—consistently, correctly, safely. We train longer, specialize more, use ever-advancing technologies, and still fail. Knowledge has both saved us and burdened us. We need to have more of an understanding of how we train. The Interim Report of the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing (2015) stated the following regarding training:

As our nation becomes more pluralistic and the scope of law enforcement’s responsibilities expands, the need for more and better training has become critical. Today’s line officers and leaders must meet a wide variety of challenges including international terrorism, evolving technologies, rising immigration, changing laws, new cultural mores, and a growing mental health crisis. All states, territories, and the District of Columbia should establish standards for hiring, training, and education. (p. 51)

Civil Litigation

Many officers and their departments find themselves involved in litigation, and many times this leads to the officers, as well as the department, having to pay huge sums of money as a result of lawsuits. Civil attorneys have become more astute in examining the training records of the officer(s). What were the officers taught, how were they assessed, what standards were they expected to meet, did they meet those standards? How was the training documented? This includes not only basic training and advanced training, but also in-service training. Though statistics on civil litigation against law enforcement agencies are not tracked, and are easily hidden, Gaines and Kappeler (2011) estimated that more than 30,000 civil actions have been filed against police officers each year over the past 15 years; that number is increasing every year, and the amount paid to litigants is estimated way into hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars.

City of Canton, Ohio v. Geraldine Harris is a Supreme Court ruling in 1989 addressing law enforcement training, or failure to train. According to the Supreme Court in the Canton ruling, training of police is a management responsibility. The agency can be held liable if the training provided to an officer is inadequate or improper, which causes injury or violates a citizen’s constitutional rights (McNamara 2006).

The Three-Prong Test

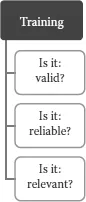

An agency should consider a three-prong test when conducting training (Figure 1.1).

The validity of training refers to the accuracy of training—whether or not it prepares the officer to perform a specific task at an expected level of proficiency. The best way to understand this idea is to ask yourself this question: “Is the training providing the officer with the skill(s) necessary to perform in his or her current work environment?”

Figure 1.1Three-prong test for training.

Reliability is a measure of administering the same training to different groups of officers and the results are relatively the same. Reliability is about consistency. The question you ask yourself regarding reliability is: “Can every officer we trained perform the same task in his or her current work environment as he (or she) was trained to do?”

Relevancy pertains to the issue of whether what is being trained is actually used in the officers’ job. Are officers being trained to what is current with law, policy, procedure, equipment, and skills needed to perform the job today? The question you ask yourself here is: “Do the officers need to know this, or do the officers use this?” Even if your training is reliable, it may not be valid or relevant, meaning if every officer can perform the task the same in his workplace as in training does not mean it is relevant or necessary for the officer to perform his or her job.

Conditions for the Transfer of Training

There are four conditions (Figure 1.2) that need to be met to ensure the material covered during training is transferred to field work:

1.Motivated Officers—Officers should be motivated and ready to learn.

2.Well-Built Curriculum—The curriculum needs to be designed and developed to provide enhanced task to performance instruction and evaluation.

3.Qualified Instructors—Instructors have to be qualified to teach what they are teaching.

4.Conducive Environment—The training environment has to have maintained equipment and facilities that provide a safe and realistic learning venue.

Figure 1.2Conditions for transfer of training.

All these conditions need to work in harmony with each other. Diminishing one condition reduces the transfer of training.

We have to recognize that training is just one aspect of an officer’s performance. There are other variables that come into play that we will examine in more detail later in this book. However, the impact of training is a critical matter for any law enforcement agency because performance can be enhanced and training can build capacity (Intergovernmental Studies Program 2006). Further, law enforcement agencies are striving to enhance performance from personnel, and training professionals are expected to deliver results (Burke and Hutchins 2008). Law enforcement agencies have to learn to work smarter and to conduct training in a more efficient manner. The days of the “sage on the stage” instructor standing in front of the classroom are numbered as improvement in technology and training methodologies has enhanced such training modalities as collaborative, experiential, and online learning. Law enforcement instructors should learn to become facilitators of learning and not “sages on the stage.” This is not to be misinterpreted in saying that instructors are going to be replaced by technology, or that simulations are going to replace real-world training models; that is not the message. The message is that law enforcement agencies should become more adaptable and progressive in how they deliver training. Everything is faster, more interconnected, and less predictable. Getting aligned with the new world is the road to longevity for any training academy or program, as well as the fulfillment to your officers. Before you conduct training, you should ask yourself, “How does this training make the officers more proficient and effective in their job?”

The Realities of Training

One reality of training is that most training will yield some predictable results (Apking and Mooney 2010). Here are some predictable outcomes of training:

1.Some officers will learn valuable information from training and apply it to their job and produce concrete results.

2.Some officers will not learn anything new or will not apply the training to their job.

3.Some officers will learn some new things and try to use their newly acquired knowledge and skills, but for some reason (i.e., lack of opportunity, time pressure, lack of initial success, lack of accountability, or lack of supervisor reinforcement), they will give up and go back to their old ways.

Another reality in training is not everything has to be trained; formal training may not be the answer, and many times it gets overused. Training law enforcement officers is an expensive enterprise. Millions of dollars are spent every year training law enforcement officers. Many times, training is ordered based on a single incident. The common answer to organizational issues is “let’s conduct training” when formal training is not warranted. Elliott and Folsom (2013, p. 167) state: “Often management relies too heavily on training as a universal response to inadequate performance. Further, managers frequently confuse training with learning; losing sight of the fact that training is in l...