- 186 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Sedation is a vital tool for allowing investigations and procedures to be performed without full anaesthesia, but demand for sedation greatly outstrips the supply of trained anaesthetists. Sedation requires care if it is to be used correctly and modern seditionists, including junior doctors in all specialities, medical students, anaesthetists, dentists, and theatre, dental and paediatric nurses, must be able to demonstrate they can practice safely. They need a sound understanding of the basic sciences involved, and an intimate knowledge of the required standards of practice. This book is a first-line educational resource for all those training in the techniques of sedation, and for those already practising who wish to consolidate their knowledge in a structured way.This highly practical handbook is therefore ideal for experienced and novice practitioners alike. It covers basic principles including patient selection and assessment, pharmacology, resuscitation competencies, monitoring equipment and legal issues, and the numerous clinical scenarios bring pertinent issues to life, emphasising the importance of safe practice. It is a unique universal introduction for practitioners from any clinical background.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Sedation for procedures, treatments and investigations: a general introduction

Terms to be used

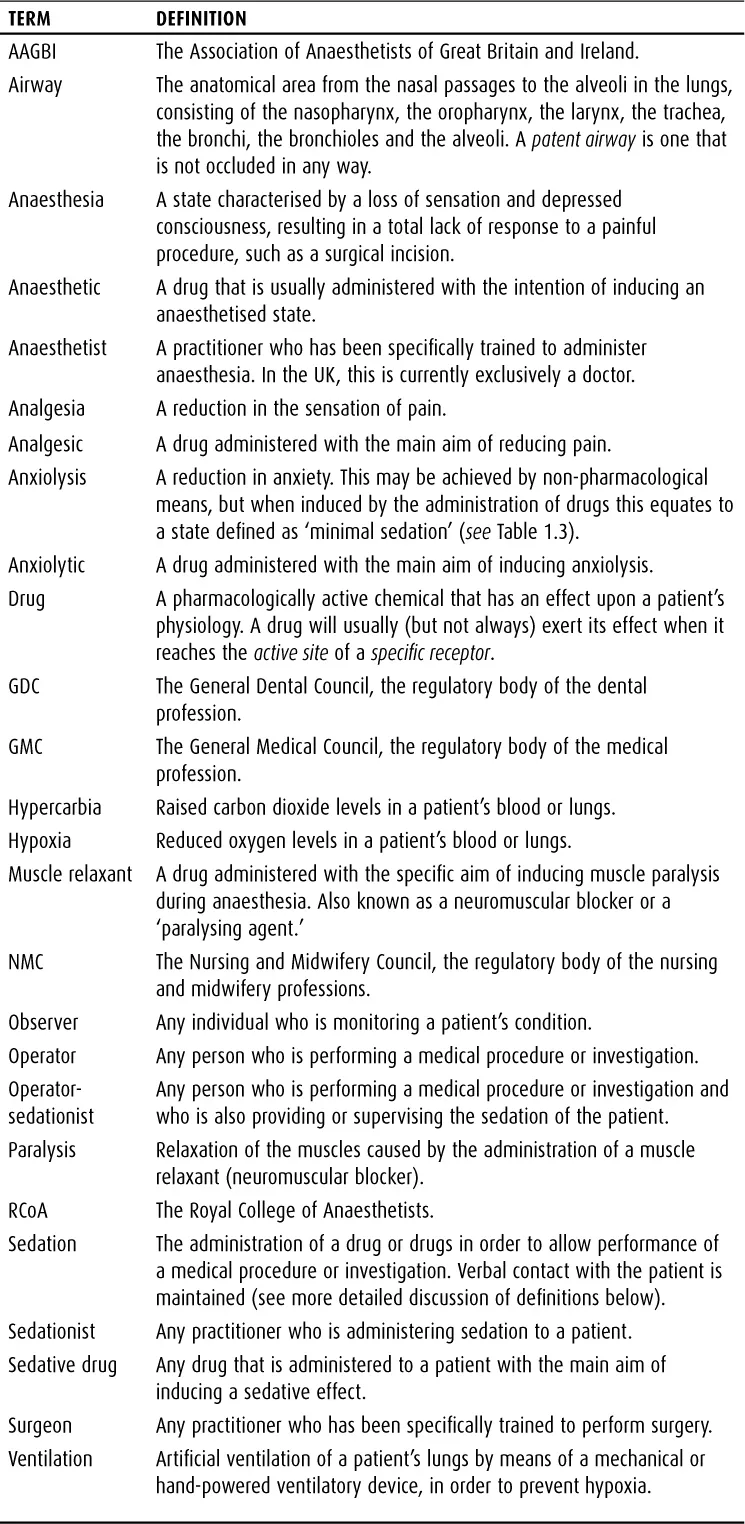

It is important that the proper meanings of terms used throughout this book are clearly understood, in order to avoid confusion. For this reason, terminology that is used frequently in the text is listed in Table 1.1 below.

TABLE 1.1 Definition of terms commonly used within this book

Definition of sedation

The first principle of safe practice is to know exactly what is meant by the term ‘sedation’, and thereby to gain a firm understanding of what can, and cannot, be achieved when it is utilised. The word ‘sedation’ is commonly used as a generic term, implying the ‘calming’ of a patient.

A simple general description of sedation for the purpose of medical procedures would be as follows:

A technique in which a drug or drugs produce depression of the central nervous system, enabling treatment to be carried out without physical or psychological stress, but during which verbal contact with the patient is maintained.

This definition is compiled from those used in many reports published by a variety of professional bodies. Some of the reports include the qualification that:

The drug(s) and techniques used should have a wide margin of safety that makes accidental loss of consciousness unlikely.

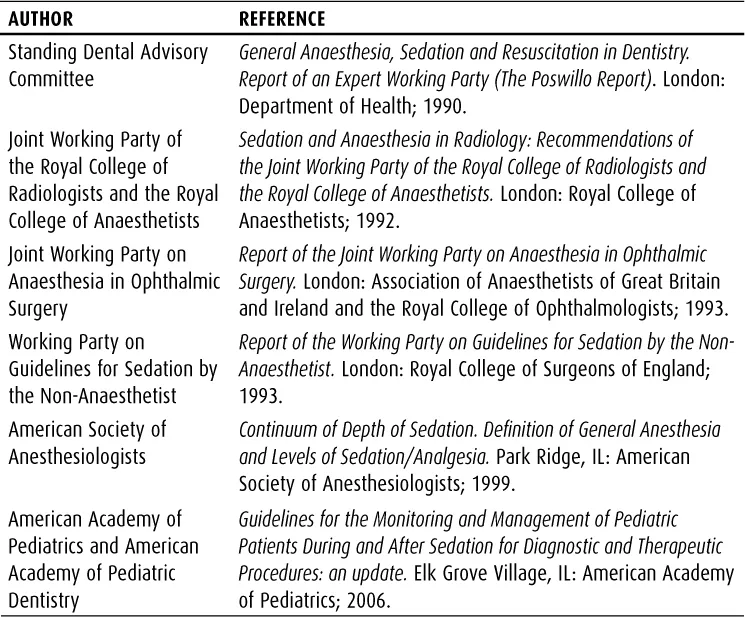

A selection of the relevant guidelines is shown in Table 1.2.

TABLE 1.2 Selection of relevant professional guidelines on sedation

This definition of sedation is seemingly straightforward, but the implication is that sedation is not a well-defined ‘end point’, but rather a continuum between the fully awake and the fully anaesthetised state.1,2 –3

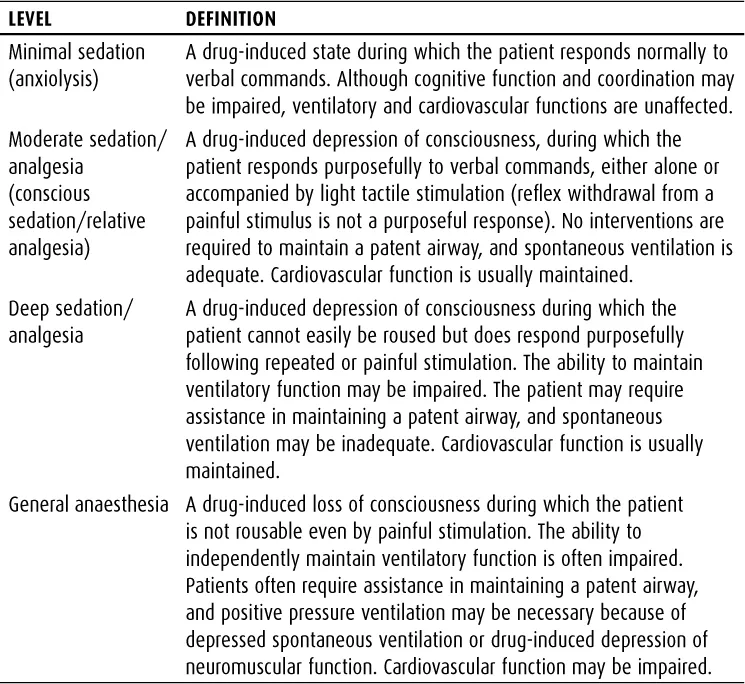

More precise definitions of the different possible levels of sedation have been suggested, and are listed in Table 1.3. These terms will be used again during the course of this book. It is obvious from reading these definitions that the transition between one level and another is quite ‘soft’, and that as a result it may be difficult to isolate chronologically when the patient becomes ‘deeply sedated.’ The transition to a level of general anaesthesia is, by contrast, very clear, because the patient becomes unresponsive to normal stimuli.

It therefore follows that whoever is administering the sedation to the patient must ensure that the patient’s well-being is adequately monitored, and must be prepared to deal with the consequences of unanticipated problems, including the attainment of a deeper level of sedation than was intended. In addition, it should be noted that, in the UK, deep sedation/analgesia is regarded as part of the spectrum of general anaesthesia, and not as a ‘level of sedation.’ Therefore the management of deep sedation in the UK is assumed to require training to the same standards of vigilance and skill as those required by an anaesthetist.4 The term ‘deep sedation’ can therefore be equated to a state of ‘light anaesthesia’, although many anaesthetists would dispute that such a state exists (i.e. a patient is either anaesthetised, or they are not). This also means that studies of sedation practice from the USA and the UK may differ greatly in what they are attempting to achieve, and so the resulting recommendations may also not be universally applicable.

It can be concluded from this that a sedative drug is a medication that globally depresses the functions of the central nervous system (CNS). Although this will have the advantage of reducing anxiety and inducing calm, it can also lead to loss of protective airway reflexes, and depression of respiratory and cardiovascular systems. It has been estimated that in paediatric sedation, the incidence of significant hypoxia may be 0.4%.5

The notion that sedation is a drug-induced interim state somewhere between full consciousness and anaesthesia, and that it is a continuum rather than a single well-defined entity, can be a difficult one for a training sedationist to grasp. In order to consolidate understanding of what sedation actually is, it is therefore also helpful to define exactly what it is not. Sedation is not synonymous with the terms ‘analgesia’ or ‘muscle relaxation.’ For example, sedation will help a patient to remain calm and relaxed for a bronchoscopy examination, but will not abolish the discomfort of a bronchoscope passing through the nasal passages or larynx; it will help a patient to remain comfortable on an operating table, but will not stop them reacting to a surgeon’s incision.

TABLE 1.3 Definitions of the levels of sedation

Analgesia

Analgesia has a very specific meaning, namely a reduction in the sensation of pain. This concept is very easily understood, because pain is either present or it is not – and if it is present, a therapeutic intervention may reduce the sensation completely, partially or not at all.

Many different medications can be used to reduce the sensation of pain. They can either be administered to or near the site of pain (such as a local anaesthetic injection), or they can be administered systemically to the whole patient (by inhalation, ingestion, injection, etc.). Some of these drugs have very powerful side-effects, which may include sedation. However, sedation is not the main effect of the drug, and so the fact that it has sedative side-effects does not mean that the drug can safely be used with the intention of inducing a sedative state. Sedative effects may in fact make the drug hazardous to use in some circumstances, or difficult to use in combination with actual sedatives, as the effects may be additive and unpredictable.

In contrast, most sedative drugs do not have a pain-relieving effect. Therefore the induction of a sedative state will not be expected to reduce the sensation of pain.

Muscle relaxation

Within anaesthesia, this is a term that has a very specific definition, namely the administration of neuromuscular blocking agents to a patient in order to relax (i.e. totally paralyse) the muscles in order to allow surgery or positive pressure ventilation. These drugs will all stop the patient breathing for a significant period of time, and require that ventilation is actively supported to prevent the patient from dying of hypoxia. The use of such muscle relaxants will render the patient totally immobile, which may mask any signs that the patient is actually fully awake rather than anaesthetised.

Muscle-paralysing agents should not be used as part of any sedative regime, nor should they even be drawn up into a syringe unless a person specifically trained in their use is present.

Outside of anaesthesia, the term ‘muscle relaxation’ can refer to the effect of drugs that reduce muscle tension. Some sedative drugs have spasm-reducing effects. These effects are not additive with those of muscle relaxants.

The purpose of sedation

In the context of this book, the purpose of sedation is to allow a procedure, treatment or investigation to be performed. Sedation is therefore not an end in itself, but a process which facilitates another outcome. It is likely that there may be an increased focus on the use of sedation for minor surgical procedures in the UK, as there is an increasing emphasis on the performance of surgery on a day-case basis both in hospitals and in general practitioner surgeries.6,7

The duties and competencies of the sedationist will be dealt with in more detail in other chapters. It is vital to remember that the sedationist is present primarily in order to serve the needs of the patient, rather than the requirements of the operator, and the safety of the patient takes priority over the performance of the procedure. Equally, however, there is no point in subjecting the patient to sedation if the desired result (performance of an adequate procedure) is not achievable.

As the first consideration of the sedationist should always be the safety of the patient, the sedationist should ask whether sedation is actually required at all, or whether in fact referral for anaesthesia is the best option. The answer to this question will depend upon multiple factors, including the technicalities of the proposed procedure (e.g. the time taken, the degree of discomfort anticipated, the position the patient may have to adopt, etc.). For example, it has been suggested that although it is more labour and resource intensive, general anaesthesia for MRI scanning in children may result in better-quality images, due to more reliable patient immobility than can be achieved with sedation.8

Once the decision has been made to provide sedation, the sedationist must ensure that everything has ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- About the author

- 1 Sedation for procedures, treatments and investigations: a general introduction

- 2 Training in sedation

- 3 Patient assessment and selection

- 4 Principles of safety in sedation

- 5 Drugs in sedation practice

- 6 Medico-legal aspects of sedation

- 7 Sedation in paediatric practice

- 8 Sedation and the elderly

- 9 Sedation in community dental practice

- 10 Sedation for radiological procedures

- 11 Sedation in critical care

- 12 Sedation in palliative care

- 13 Sedation for miscellaneous procedures

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Safe Sedation for All Practitioners by James Watts,Pascale Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Theory, Practice & Reference. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.