- 126 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Managing Risk in Projects

About this book

Projects are risky undertakings, and modern approaches to managing projects recognise the central need to manage the risk as an integral part of the project management discipline. Managing Risk in Projects places risk management in its proper context in the world of project management and beyond, and emphasises the central concepts that are essential in order to understand why and how risk management should be implemented on all projects of all types and sizes, in all industries and in all countries. The generic approach detailed by David Hillson is consistent with current international best practice and guidelines (including 'A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge' (PMBoK) and the 'Project Risk Management Practice Standard' from PMI, the 'APM Body of Knowledge' and 'Project Risk Analysis & Management (PRAM) Guide' from APM, 'Management of Risk: Guidance for Practitioners' from OGC, and the forthcoming risk standard from ISO) but David also introduces key developments in the risk management field, ensuring readers are aware of recent thinking, focusing on their relevance to practical application. Throughout, the goal is to offer a concise description of current best practice in project risk management whilst introducing the latest relevant developments, to enable project managers, project sponsors and others responsible for managing risk in projects to do just that - effectively.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Uncertainty and Risk

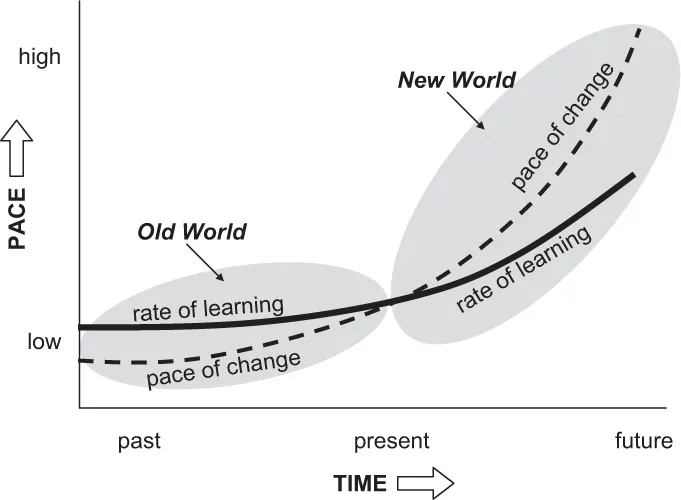

Current Sources of Uncertainty

Responding to Uncertainty

Distinguishing Between Uncertainty and Risk

TERM | UNCERTAINTY | RISK |

Dictionary (Collins, 1979) | Lacking certainty; not able to be accurately known or predicted; not precisely determined, established or decided; liable to variation; changeable. | Possibility of incurring misfortune or loss; hazard; involving danger, perilous. |

Thesaurus (Roget, 2008) | Ambiguity, ambivalence, anxiety, changeableness, concern, confusion, conjecture, contingency, dilemma, disquiet, distrust, doubtfulness, guesswork, hesitancy, hesitation, incertitude, inconclusiveness, indecision, irresolution, misgiving, mistrust, mystification, oscillation, perplexity, qualm, quandary, query, reserve, scruple, scepticism, suspicion, trouble, uneasiness, unpredictability, vagueness. | Accident, brinksmanship, contingency, danger, exposure, fortuity, fortune, gamble, hazard, jeopardy, liability, luck, openness, opportunity, peril, possibility, prospect, speculation, uncertainty, venture, wager. |

Table of contents

- Cover-Page

- Managing Risk in Projects

- Copyright Page

- Content Page

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Foreword by Simone Wray

- Author’s Preface

- Chapter 1 Uncertainty and Risk

- Chapter 2 Risk and Projects

- Chapter 3 Managing Risk in Practice

- Chapter 4 Risk and People

- Chapter 5 Integrating Risk Management With Wider Project Management

- Chapter 6 The Bigger Picture

- Chapter 7 Making Risk Management Work

- References and Further Reading

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app