1.2.1 Introduction

Concurrent engineering (CE) is a present-day method used to shorten the time to market for new or improved products. Let it be assumed that a product will, upon reaching the marketplace, be competitive in nearly every respect, such as quality and cost, for example. But the marketplace has shown that products, even though competitive, must not be late to market, because market share, and therefore profitability, will be adversely affected. Concurrent engineering is the technique that is most likely to result in acceptable profits for a given product.

A number of forwarding-looking companies began, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, to use what were then innovative techniques to improve their competitive position. But it was not until 1986 that a formal definition of concurrent engineering was published by the Defense Department:

A systematic approach to the integrated, concurrent design of products and their related processes, including manufacture, and support. This approach is intended to cause the developers, from the outset, to consider all elements of the product life cycle from concept through disposal including quality, cost, schedule, and user requirements.

This definition was printed in the Institute for Defense Analyses Report R-338, 1986. The key words are seen to be integrated, concurrent design and all elements of the product life cycle. Implicit in this definition is the concept that, in addition to input from the originators of the concept, input should come from users of the product, those who install and maintain the product, those who manufacture and test the product, and the designers of the product. Such input, as appropriate, should be in every phase of the product life cycle, even the very earliest design work.

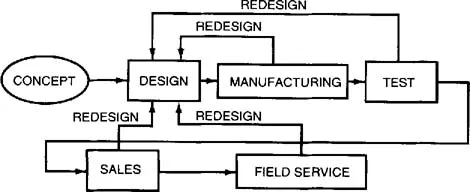

This approach is implemented by bringing specialists from manufacturing, test, procurement, field service, etc., into the earliest design considerations. It is very different from the process so long used by industry. The earlier process, now known as the over the wall process, was a serial or sequential process. The product concept, formulated at a high level of company management, was then turned over to a design group. The design group completed its design effort, tossed it over the wall to manufacturing, and proceeded to an entirely new and different product design. Manufacturing tossed its product to test, and so on through the chain. The unfortunate result of this sequential process was the necessity for redesign, which happened regularly.

Traditional designers too frequently have limited knowledge of a manufacturing process, especially its capabilities and limitations. This may lead to a design that cannot be made economically or in the time scheduled, or perhaps cannot be made at all. The same can be said of the specialists in the processes of test, marketing, and field service, as well as parts and material procurement. A problem in any of these areas might well require that the design be returned to the design group for redesign. The same result might come from a product that cannot be repaired. The outcome is a redesign effort required to correct the deficiencies found during later processes in the product cycle. Such redesign effort is costly in both economic and time to market terms. Another way to view these redesign efforts is that they are not value added. Value added is a particularly useful parameter by which to evaluate a process or practice.

This presence of redesign in the serial process can be illustrated as in Fig. 1.1, showing that even feedback from field service might be needed in a redesign effort. When the process is illustrated in this manner, the presence of redesign can be seen to be less efficient than a process in which little or no redesign is required. A common projection of the added cost of redesign is that changes made in a following process step are about 10 times more costly than correctly designing the product in the first place. If the product should be in the hands of a customer when a failure occurs, the results can be disastrous, both in direct costs to accomplish the repair and in possible lost sales due to a tarnished reputation.

There are two major facets of concurrent engineering that must be kept in mind at all times. The first is that a concurrent engineering process requires team effort. This is more than the customary committee. Although the team is composed of specialists from the various activities, the team members are not there as representatives of their organizational home. They are there to cooperate in the delivery of product to the market place by contributing their expertise in the task of eliminating the redesign loops shown in Fig. 1.1. Formation of the proper team is critical to the success of most CE endeavors. The second facet is to keep in mind is that concurrent engineering is information and communication intensive. There must be no barriers of any kind to complete and rapid communication among all parts of a process, even if they are located at geographically dispersed sites. If top management has access to and uses information relevant to the product or process, this same information must be available to all in the production chain, including the line workers.

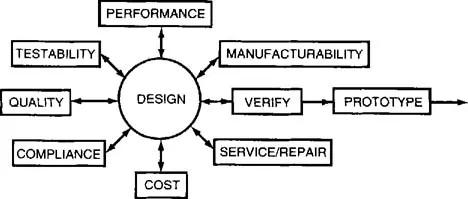

An informed and knowledgeable workforce at all levels is essential so that they may use their efforts to the greatest advantage. The most effective method to accomplish this is to form, as early as possible in the product life cycle, a team composed of knowledgeable people from all aspects of the product life cycle. This team should be able to anticipate and design out most if not all possible problems before they actually occur. Figure 1.2 suggests many of the communication pathways that must be freely available to the members of the team. Others will surface as the project progresses. The inputs to the design process are sometimes called the “design for…,” inserting the requirement.

The top management that assigns the team members must also be the coaches for the team, making certain that the team members are properly trained and then allowing the team to proceed with the project. There is no place here for the traditional bossism of the past. The team members must be selected to have the best combination of recognized expertise in their respective fields and the best team skills. It is not always the one most expert in a specialty who will be the best team member. Team members, however, must have the respect of all other team members, not only for their expertise but also for their interpersonal skills. Only then will the best product result. This concurrence of design, to include these and all other parts of the cycle, can measurably reduce time to market and overall investment in the product.

Preventing downstream problems has another benefit in that employee morale is very likely to he enhanced. People almost universally want to take pride in what they do and produce. Few people want to support or work hard in a process or system that they believe results in a poor product. Producing a defective or shoddy product does not give them this pride. Quite often it destroys pride in workmanship and creates a disdain for the management that asks them to employ such processes or systems. The use of concurrent engineering is a very effective technique for producing a quality product in a competitive manner. Employee morale is nearly always improved as a result.

Perhaps the most important aspect of using concurrent engineering is that the design phase of a product cycle will nearly always take more time and effort than the original design would have expended in the serial process. However, most organizations that have used concurrent engineering report that the overall time to market is measurably reduced because product redesign is greatly reduced or eliminated entirely. The time-worn phrase time is money takes on added meaning in this context.

Concurrent engineering can be thought of as an evolution rather than a revolution of the product cycle. As such, the principles of total quality management (TQM) and continuous quality improvement (CQI), involving the ideas of robust design and reduction of variation, are not to be ignored. They continue to be important in process and product improvement. Nor is concurrent engineering, of itself, a type of re-engineering The concept of re-engineering in today’s business generally implies a massive restructuring of the organization of a process, or even a company, probably because the rate of improvement of a process using traditional TQM and CQI is deemed to be too slow or too inefficient or both to remain competitive. Still, the implementation of concurrent engineering does require and demand a certain and often substantial change in the way a company does business.

Concurrent engineering is as much a cultural change as it is a process change. For this reason it is usually achieved with some trauma. The extent of the trauma is dependent on the willingness of people to accept change, which in turn is dependent on the commitment and sales skills of those responsible for installing the concurrent engineering culture. Although it is not usually necessary to re-engineer, that is, to restructure, an entire organization to install concurrent engineering, it is also true that it cannot be installed like an overlay on top of most existing structures. Although some structural changes may be necessary, the mos...