eBook - ePub

China's Economic Challenge: Smashing the Iron Rice Bowl

Smashing the Iron Rice Bowl

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book lays bare the reality behind China's efforts at economic modernization by showing: (1) what is happening to the industrial forces that help shape the economy; (2) how economic agents have behaved; (3) what government intentions really are; and (4) how the transition from a centralized to a market-oriented economy has been filled with contradictions and difficult choices. The author examines issues such as China's WTO membership; the Three Gorges Project; the widening differences between the urban and rural areas; the government's efforts to protect its own interests and maintain stability; the impact of reform; and the situation facing state enterprises, the banking system, the agricultural sector, and the environment.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access China's Economic Challenge: Smashing the Iron Rice Bowl by Neil C. Hughes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Commerce Général. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

CommerceSubtopic

Commerce GénéralChapter One

Smashing the Iron Rice Bowl

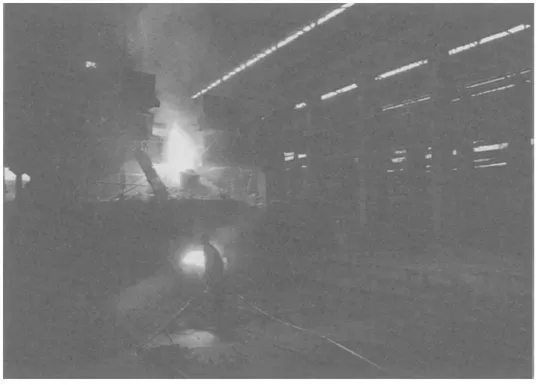

Making steel and pollution, Chongqing. A 1958 Soviet-built electric arc furnace emits bright flames, and a cloud of glowing ashes rises into the atmosphere. This furnace is scheduled to shut down at the end of 2002.

Symbols have played an important part in Chinese life since the beginning of its recorded history. For centuries, the Chinese have performed their rituals, celebrated their holidays, and adorned their personal effects with images of good fortune, long life, and prosperity. During the Communist era, symbols and slogans continue to play an important part in providing an easily remembered litany of the Communist party’s ideological themes and objectives. Rice has been China’s staple food for thousands of years, and the most important symbol of the party’s economic policies was an unbreakable iron rice bowl, which stood for the party’s commitment to provide cradle-to-the-grave security for all its citizens. When Deng Xiaoping began in 1978 to transform China from a centrally planned and controlled economy to a more open market-oriented economy, his supporters insisted that the iron rice bowl must be smashed if China was to achieve this economic transformation.

China’s dilemma is that it is afraid to smash the iron rice bowl because it fears that the social stability that has sustained its reform program will be threatened. The government is still relying on subsidies to keep redundant workers off the streets and finance its core group of large state enterprises. It is also desperately looking for buyers for thousands of smaller state enterprises, but they are hard to find and many enterprises have to be almost given away. Time is running out because the government cannot afford to continue such massive subsidies indefinitely, and World Trade Organization (WTO) membership is putting even greater competitive pressure on these enterprises.

Forging the Iron Rice Bowl

Li Hongzhang, governor general of Hebei Province and commissioner of the northern ports under the Qing empress dowager Cixi, almost single-handedly established China’s first industrial enterprises. He founded a cotton mill in Shanghai in 1878 to compete with foreign imports and established armaments factories in Tianjin in the 1880s to help modernize China’s army.1 Establishing an industrial base began in earnest in the 1890s when foreign governments that had been granted concession rights in major Chinese cities began building railways, ports, and factories to produce and transport iron and steel and export goods. Industrialization varied according to local circumstance and the vigor of foreign and local initiative. In Wuhan, for example, a mining and iron and steel complex was established in the 1890s that employed 10,000 workers. Conservative forces were opposed to development, but strong opposition all but ceased after the Boxer uprising was put down in 1900. Chinese-owned industry really began to grow only in the second decade of the twentieth century. By 1913, there were 700 Chinese factories employing 270,000 workers. By 1920, 1,700 factories employed 500,000 workers. By 1920,7,000 foreign firms were registered in China, and Shanghai had become the center of the textile industry with 100,000 workers.2

For the next two decades, industry continued to be centered in zones of foreign influence like Shanghai, Wuhan, Canton (Guangdong), and Tianjin, and foreigners still owned important parts of major industries. The Japanese invasion of 1937 changed all that. The nationalist Guomindang government fled Nanjing for the comparative safety of Chongqing in Sichuan Province. Most industries stayed in place, but a great deal of machinery and equipment was carried on the backs of people or animals across hundreds of miles of rugged terrain to Chongqing or to the Communist base at Yan’an in Shaanxi Province.

After the Communist regime took power in 1949, they borrowed the Soviet Union’s model for industrial development, which was based on a series of five-year plans focusing on capital-intensive investments in heavy industry. Most of the resources to finance industry came from agriculture and mining, either directly through the budget or indirectly through subsidized prices for food and inputs. China’s planners decided that to maintain the growth level of industry in the future, agricultural production had to be increased. There was considerable debate between those who believed that farmers should be given more economic incentives and those who believed in mass mobilization of the peasantry through appeals to self-reliance and Communist ideals. Mao Zedong was at the forefront of the latter group. He worried that as the Revolution became more and more institutionalized, individual commitment and the appeal of revolutionary ideology would be lost.

The Great Leap Forward was launched in 1957 with great fanfare, centralized allocation and planning were shelved, and new industrial production was decentralized to the commune. Based on the principle of achieving self-reliance, more than 1 million “backyard” iron and steel furnaces were built. The quality of the metal produced was atrocious and the unit cost incalculable. Agricultural production was disrupted, but no official was willing to make any report that revealed the true situation. The famine that followed in the wake of the Great Leap Forward claimed 30 million lives. Children especially suffered, as reflected in mortality data showing the median age at death, which fell from 17.6 years of age in 1957 to 9.7 years of age in 1963. One-half of the people dying in China were under ten years old, and the Great Leap Forward had turned inward upon itself and was devouring its children.3

By 1964, China faced a hostile Soviet Union on its northern borders, and Mao Zedong was worried about a possible invasion from Taiwan and of being drawn into the Vietnam War. He decided to establish a “Third Front” of heavy industry deep in the heart of China. Widely dispersed industrial complexes located in remote areas would provide, thought Mao, a strategic reserve production base if China had to go to war. For the next twelve years, this effort absorbed a large part of China’s entire national investment. Annual expenditures for Third Front factory complexes and transportation networks in the provinces of Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, Qinghai, Gansu, and Ningxia from 1964 to 1975 ranged from 38 to 53 percent of China’s entire national investment budget.4

In spite of China’s great leap backward, the Maoists remained unrepentant, and Daqing, a large, isolated industrial complex at an oil field in northern Heilongjiang Province, became a symbol of the virtues of self-reliance and hard work. “Learn from Daqing!” became a rallying cry for industrial workers all over China. The entire Chinese leadership agreed that China’s primary economic goal should be to carry out the “four modernizations” of agriculture, industry, science and technology, and national defense; but it was difficult to reach agreement over how to do it. In the early 1970s, a group of reformers, led by Zhou Enlai and including Deng Xiaoping, tried to promote the acquisition of foreign technology and technical assistance, including the importation of whole industrial plants. Although initially successful, these efforts were thwarted by the apostles of self-reliance, many of whom were in the ascendancy during the Cultural Revolution of 1968 to 1976. It was not until after Mao’s death in 1976 that Deng Xiaoping and other reformers were able to proceed with the modernization of industry by reforming existing structures and opening the country to outside influences.

Economic Reform Versus the Iron Rice Bowl

In 1978, collective farming was abandoned and replaced with the house-hold-responsibility system, which gave farmers the right to income from the crops sold from their land, introduced informal markets, and allowed farm prices to rise over a support price. These actions appeared to signal the end of the iron rice bowl. However, similar bold initiatives were not undertaken to reform state enterprise in urban areas, where the government approached tackling the more complex and contentious problem of industrial reform with much debate and more caution, first experimenting on a small scale before undertaking major reforms—“crossing the river by feeling for each stone,” as Deng Xiaoping put it.

At the Fourteenth Communist Party Congress, which took place in October 1992, China was still emerging from the shadow of the Tienanmen massacre of 1989. Deng’s spokesman, party secretary-general Jiang Zemin, reiterated China’s commitment to the reform begun in 1978 and launched a bold innovation by adopting market competition as official policy under the ideological banner of a socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics. Deng had put an end to the debate. The market was to be the main instrument for making investment decisions and allocating resources. In March 1993, the Chinese constitution was amended by the party’s Central Committee to include the concept of a socialist market economy, and the concept of a planned economy under public ownership was deleted.5

In November 1993, the Third Plenary Session of the Fourteenth Party Congress issued the “Decision on Issues Concerning the Establishment of a Socialist Market Economic System,” whose agenda featured the creation of a modern enterprise system by the year 2000, in which state enterprises would be incorporated under new legislation, usually called the company law. Government administration would be separated from day-to-day operations and enterprise managers given operational responsibility. It also encouraged diversified forms of enterprise ownership, especially privately owned, individually owned, and foreign-invested enterprises; but public ownership (broadly defined in the constitution to include enterprises owned by national, provincial, municipal, township, and village governments) would continue to be the dominant form of ownership in the economy.

If the socialist market economy was to be the central arch supporting the new economic edifice, the modern enterprise system embodying state enterprise reform would be its keystone. In 1994, major steps were begun to implement the modern enterprise system. Internationally based accounting practices were adopted. The company law was enacted, providing the legal basis for separating ownership control from the management of state enterprises and substituting a corporate legal and administrative structure for the centralized command and control system. The tax system was reformed to clarify the distinction between taxes due to the government and profits to be retained by the enterprise (lumped together prior to the reform). Direct subsidies through the budget were largely eliminated, but indirect subsidies continued to be made through the banking system. “Pillar industries” were identified, and key enterprises in these industries were incorporated at the provincial or city level to form the core of the modern enterprise system. Enterprises in the same line of business were encouraged to consolidate into large group companies—a Chinese version of the Japanese keiretsu and Korean chaebol—to reduce overhead costs and eliminate redundant production lines.

These reforms represented real but gradual progress, and much remained to be done. Many state enterprises remained mired in the wasteful use of resources and low productivity. They continued to depend upon outmoded and often polluting technologies and could not afford to replace obsolete equipment. They carried far too many workers on their payrolls and were obligated to provide a wide array of social services to their employees. Enterprise managers in most cases lacked sufficient autonomy and had not been given any incentives to respond to signals from the market.

Group consolidation proved to be a double-edged sword, for while it enabled enterprises with a clear view of where they wanted to go to restructure themselves to a more economical scale, others with more intractable problems came to depend on the group to solve them. Enterprise groups received tax benefits, access to loans from government banks and local governments, and central government support when needed. In return, enterprises with strong balance sheets were required to join forces with less successful ones, with the group providing an umbrella for those who could not survive on their own.

Prior to the Fifteenth Party Congress in September 1997, there was a good deal of speculation as to whether the issue of state enterprise reform was going to be dealt with more substantively. In Secretary-General Jiang’s speech to the Congress, he reiterated the major economic themes of the Fourteenth Congress, now enshrined under the great banner of Deng Xiaoping theory, but emphasized that reforms of medium and large state enterprises would be accelerated to complete the transition to the modern enterprise system by the year 2000.

Jiang proposed two new initiatives, major layoffs of state workers and divestiture of state enterprise. But distinctions are critical: laid-off workers in China are not unemployed; they maintain links with their work unit and receive minimal salaries. Divestiture applies only to the smaller state enterprises, which will be merged, leased, sold off, or in some cases closed down through bankruptcy. Jiang sought to maintain a consistent ideological stance and insisted that divestiture is not privatization, it is rather a necessary part of the primary stage of socialism, which China is still undergoing. Subsequently, the government indicated its willingness to divest itself of larger-scale state enterprises, and stated that more than 10,000 of China’s 13,000 medium and large state enterprises would be sold off. The goal was to reduce the number of state enterprises to a core of large group companies. This was a major admission by the government that it would no longer be the dominant force in industry. By the end of 1998, the government had approved 2,472 large enterprise groups with total assets of US$806 billion, or over one-half the total assets of all state enterprises.6 China was on its way to following the Japanese and Korean example of a mixed public-private economy in which state enterprises have the advantage of political backing, access to state funding, and high-level guanxi contacts (relationships based on exchange of favors).

Jiang insisted that reform was only possible because of stability: “Without stability, nothing could be achieved…. [We] must uphold the leadership of the party and the people’s democratic dictatorship.“7 Jiang’s message is clear: Only the party can guarantee stability and carry off the reform program. But can it? Selling off state enterprises and accepting that many workers will lose their jobs and benefits in the process represents an enormous gamble for Jiang.8

At the Ninth National People’s Congress, which met in March 1998, Zhu Rongji was sworn in as China’s new premier. He put his reputation on the line by assuring the delegates that the accelerated reform would indeed be completed by 2000. Outgoing premier Li Peng, in his report on government, announced a giant step backward: a return to massive direct subsidies to try to reverse the unprofitability of China’s key industries, beginning with its most troublesome industry, textiles. This was a first step in the government’s plan to modernize China’s key industries and bring into being the modern enterprise system by the year 2000.

In the textile industry in 1996, there were 4,031 state-owned firms, (including 280 enterprises that were “restructured” and merged to form 100 group companies), employing 4 million workers and operating 41.7 million spindles. Since 1993, the industry had suffered continuing deficits, amounting to US$1.28 billion in 1996 and US$963 million in 1997. The situation was so serious in 1997 that one government official stated that 40 percent of these enterprises were “on the brink of bankruptcy.”9

It is ironic but instructive that China is the world’s biggest exporter of textile products, which amount to one-fourth of all China’s exports. China’s textile exporters are competing in the international market in one of the most fiercely competitive industries in the world, while a much larger number of enterprises producing for the domestic market is mired in obsolescence, inefficiency, and gross overcapacity. The government’s strategy was to reduce overcapacity and obsolescence by providing subsidies for enterprises that agreed to eliminate up to an aggregate of ten million spindles. For every 10,000 spindles taken out of production, enterprises received US$600,000 in a blend of cash and low-interest loans. In addition, the government as owner swapped debt for equity by buying up bad loans from these enterprises. In 1997, US$1.2 billion in debt was converted to equity in 555 state textile enterprises, and double this amount was allocated for the same purpose in 1998. About 9.06 million spindles were taken out of production, and 1.16 million workers became redundant. But some of the spindles found their way back into production again (there were twenty such instances in the first six months of 2000).10 In 1999, the government claimed that the textile industry as a whole had finally become profitable. About 2,000 textile enterprises were declared to be of national significa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Map of China

- 1. Smashing the Iron Rice Bowl

- 2. Like Stones Dropped in the Sea

- 3. The Good Earth

- 4. Cities Without Walls

- 5. The Three Gorges Dam Revisited

- 6. Cyberspace Gatekeeper

- 7. From Dragon Robe to Business Suit

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index