- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Do Elections Matter?

About this book

This text provides an analysis of the variety of consequences that elections may have for the operation of American political institutions and the formulation and administration of policy.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

HOW DID THE 1994 ELECTION MATTER?

The 1994 election results took most observers of the United States by surprise. For political scientists, regardless of their particular ideologies or policy preferences, the election was a blessing because it ignited intense debate on a variety of issues. The essays in this book examine many of the issues, but they do not definitively answer the questions. Rather, we hope that the issues are refined and sharpened beyond the extent to which the citizen and student is exposed in his or her newspaper or by his or her pontificating broadcaster. Political science, in this respect, mirrors politics but is superior to it because the discussions are, at their best, carried out at a higher level. We have made every effort to assure that the discussions in this book are at a decent level.

A specific election result, on the one hand, may have little to tell us about past or future elections or the probable public policies they portend. That is, an election may be a unique event. On the other hand, a particular election may portend the beginning or continuation of a trend in elections or policies. The 1994 election was clearly associated with a collection of policies that Speaker of the House of Representatives Newt Gingrich developed and most Republican Party candidates accepted. It is hard to recall when the candidates of a major party have been as united about a package of policies as they were about the "Contract with America" that Gingrich designed. It is also clear that most Republican candidates at the national level in 1994 publicized their endorsement of the "Contract with America" and that the Democrats, especially President Bill Clinton, ridiculed and attacked the document. It was not uncommon for Democratic pundits to view the "Contract with America" as a Republican strategic blunder.

And then it happened. The Republican victory was extraordinary, even for a mid-presidential term election in which dissatisfactions are usually focused on the president's party. The Republican victory occurred not just at the national level but at the state and local ones as well. The Democrats lost a greater percentage of their open House seats than any party has done in a congressional election since 1790. Defection upon defection has occurred in Democratic ranks, and so on. But does this extraordinary election signal a long-term shift, or is it indicative of temporary disaffection? The question will remain definitively unanswered, regardless of the 1996 results. Yes, there is widespread voter dissatisfaction. On the one hand, certainly the collapse and public distrust of the centerpiece of Clinton's program—health care reform—as well as unease concerning the president's character and abilities did not help the Democratic cause. But, on the other hand, there is little evidence that the public accepted, or even understood, the details of the "Contract with America."

We are left, then, with more questions than answers. The essays in this book reflect the divisions of opinion within the scholarly community. The issues are approached in a variety of ways, including comparatively, historically, and analytically. At the end of the book, the reader may be left with many questions, but we trust that these will be at a higher level than before undertaking this journey.

1.1

The 1994 National Elections

A Debacle for the Democrats

Benjamin Ginsberg

After two years of legislative struggle, the Clinton administration suffered a stunning defeat in the November 1994 national election. For the first time since 1946, Republicans won simultaneous control of both houses of Congress. This put the GOP in a position to block President Clinton's legislative efforts and to promote its own policy agenda.

In Senate races, the Republicans realized a net gain of eight seats to achieve a 52—48 majority. Immediately after the election, Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama, a conservative Democrat who frequently voted with the Republicans, announced that he was formally joining the GOP. This gave the Republicans fifty-three votes in the upper chamber. In House races, the Republicans gained an astonishing fifty-two seats to win a 230 to 204 majority (one seat is held by an independent). Subsequent party switches gave the Republicans a 55–45 edge in the Senate and a 232—202 House majority by mid-1995. While the Republicans had controlled the Senate as recently as 1986, the House of Representatives had been a Democratic bastion since 1954.

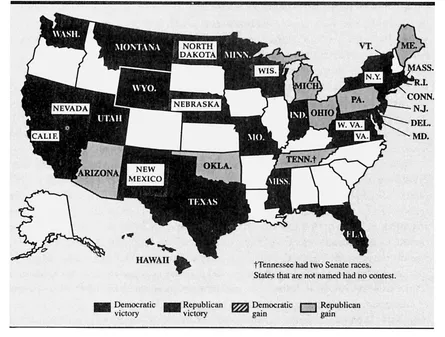

Republicans also posted a net gain of eleven governorships and won control of fifteen additional chambers in state legislatures, A number of the Democratic Party's leading figures were defeated. These included Governor Mario Cuomo of New York, former House Ways and Means Committee chair Dan Rostenkowski of Illinois, House Judiciary Committee chair Jack Brooks of Texas, three-term Senator Jim Sasser of Tennessee and, most shocking of all, House Speaker Thomas Foley of Washington. Foley was the first sitting Speaker to be defeated for reelection to his own congressional seat since 1860. All told, thirty-four incumbent Democratic representatives, three incumbent Democratic senators, and four incumbent Democratic governors were defeated. On the Republican side, not one of the ten incumbent senators, fifteen incumbent governors, or 155 incumbent House members seeking reelection was defeated. The South, which had voted Republican in presidential elections for twenty years, now seemed to have turned to the GOP at the congressional level as well. Republicans posted gains among nearly all groups in the populace, with white, male voters, in particular, switching to the GOP. The nation's electoral map had been substantially altered (Figure 1). Interest in the hard-fought race had even produced a slight increase in voter turnout, albeit to a still abysmal 39 percent.

In the wake of their electoral triumph, Republicans moved to name Robert Dole of Kansas to the post of Senate majority leader and Representative Newt Gingrich of Georgia to the House speakership. Only two years earlier, Gingrich had been widely viewed as a Republican "firebrand" whose vitriolic attacks on the House leadership were usually dismissed by the media as dangerous and irresponsible. Other Republicans who would move to leadership positions included archconservative Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who replaced Sam Nunn of Georgia as chairperson of the Senate Armed Services Committee, and outspoken Clinton critic Alphonse D'Amato of New York, who would now head the Senate Banking Committee. At the same time, Representative Floyd Spence, a conservative South Carolinian, replaced Ron Dellums of California, an avowed pacifist, as chairperson of the House Armed Services Committee.

The 1994 election seemed to represent a nationwide repudiation of the Democratic Party. Why did this occur? Why, after two years, had the Clinton administration's bright beginnings and promises of "change" ended with an electoral disaster? What would the election mean for the Democratic and Republican Parties and for the nation?

Origins of Republican Success

The roots of the 1994 Democratic debacle can be traced back to the events of the late 1960s that helped to reshape both major U.S. political parties. From the 1930s through the mid-1960s, the Democratic Party was the nation's dominant political force. The Democrats were led by a coalition of southern white politicians and northern urban machine bosses and labor leaders. The party drew its votes primarily from large cities, from the South, and from minorities, unionized workers, Jews, and Catholics.

Though occasionally winning presidential elections and, less often, control of Congress, the Republicans had been the nation's minority party since Franklin Roosevelt's victory and the beginnings of the New Deal in 1933. The Republicans were led by northeastern and midwestern Protestants whose roots were in the business community. The GOP drew its support primarily from middle- and upper-middle class suburban voters in the northeast, from rural areas, and from the small towns and cities of the midwest.

Figure 1. 1994 Races for the Senate

Civil Rights, the Vietnam War, and National Party Politics

In the 1960s, two powerful tidal waves brought about the reconstruction of both national party coalitions. These were the anti–Vietnam War movement and the Civil Rights movement. The anti–Vietnam War movement galvanized liberal activists in the Democratic Party. These activists attacked and, during the late 1960s, destroyed much of the power of the machine bosses and labor leaders who had been so prominent in Democratic Party affairs. Liberal activists proceeded to organize a congeries of "public interest" groups to fight on behalf of such liberal goals as consumer and environmental regulation; an end to the arms race; expanded rights and opportunities for women, gays, and the physically handicapped; and gun control. These groups struggled for the election of liberal congressional and presidential candidates, as well as for legislation designed to achieve their aims. During the 1970s, liberal forces in Congress were successful in enacting significant pieces of legislation in many of these areas.

For its part, the Civil Rights movement attacked and sharply curtailed the power of the southern white politicians who had been the third leg of the Democratic Party's leadership troika. In addition, the Civil Rights movement brought about the enfranchisement of millions of African American voters in the South, nearly all of whom could be counted upon to support the Democrats. These developments dramatically changed the character of the Democratic Party.

The New Democratic Party

The new prominence and energy of liberal activists in the Democratic Party after the late 1960s added greatly to the Democratic advantage in local and congressional elections. Democrats already possessed an edge in this arena because of incumbency effects. Democrats had usually controlled Congress and a majority of state and local offices since the New Deal. Incumbents have many electoral advantages and, more often than not, are able to secure reelection. Particularly important, of course, is the ability of incumbents to bring home "pork" in the form of federal projects and spending in their districts. In general, the more senior the incumbents, the more pork they can provide for their constituents. Thus, incumbency worked to perpetuate Democratic power by giving voters a reason to cast their ballots for the Democratic candidate regardless of issues and ideology.

Democrats, however, were far more successful than Republicans in congressional and local races even in contests to fill open seats where they did not possess the advantage of incumbency. Until recent years, at least, these races tended to be fought on the basis of local rather than national issues. Victory in these elections, moreover, depended upon the capacity of candidates to organize armies of volunteers to hand out leaflets, call likely voters, post handbills, and engage in the day-to-day efforts needed to mobilize constituent support.

Their armies of liberal activists gave Democratic candidates the equivalent of an infantry force on the ground that the Republicans could seldom match. Therefore, even when incumbent Democrats died or retired, they were usually replaced by other Democrats. In this way, Democratic control of Congress was perpetuated. Moreover, because the Democratic activists who were so important in congressional races were liberals who tended to favor like-minded Democratic candidates, the prominence of somewhat left-of-center forces within the Democratic congressional delegation increased markedly after the 1960s.

Republican Advantage

The same liberal activism, however, that helped propel the Democrats to victory in congressional elections often proved to be a hindrance in the presidential electoral arena. Particularly after the 1968 Democratic presidential election and the party's adoption of new nominating rules based upon the recommendations of the McGovern-Fraser Commission, liberal activists came to play a decisive role in the selection of Democratic presidential candidates. Though Democratic liberals were not always able to name the candidate of their choosing, they were in a position to block the nomination of candidates they opposed.

The result was that the Democratic nominating process often produced candidates who were seen as too liberal by much of the general electorate. This perception contributed to defeat after defeat for Democratic presidential candidates. For example, in 1972, Democratic candidate George McGovern suffered an electoral drubbing at the hands of Richard Nixon after proposing to decrease the tax burden of lower-income voters at the expense of middle- and upper-income voters. Similarly, in 1984, Democratic candidate Walter Mondale was routed by Ronald Reagan after pledging to increase taxes and social spending if elected.

The Democratic Party's difficulties in presidential elections were compounded by the aftermath of the Civil Rights movement. The national Democratic Party had helped to bring about the enfranchisement of millions of black voters in the South. To secure the loyalty of these voters as well as to cement the loyalty of black voters in the North, the national Democratic leadership supported a variety of civil rights and social programs designed to serve the needs of African Americans.

Unfortunately, however, the association of the national Democratic Party with civil rights and the aspirations of blacks had the effect of alienating millions of white Democrats, including southerners and blue-collar northerners, who felt that black gains came at their expense. Alienated white voters defected to George Wallace's third-party candidacy in the 1968 presidential contest. Subsequently, many began voting for Republican presidential candidates.

Efforts by Democratic presidential candidates to rebuild their party's support among southern whites and blue-collar Northerners were hampered by the harsh racial arithmetic of U.S. politics. In the wake of the Voting Rights Act, the Democratic Party depended upon African Americans for more than 20 percent of its votes in national presidential elections. At the same time, the Democrats relied upon whites who, for one reason or another, were unfriendly to blacks for a more or less equal portion of their strength in presidential races. This meant that efforts by Democratic candidates to bolster their support among blacks by focusing on civil rights and social programs tended to lose as much support among whites as was gained among blacks. Conversely, Democratic candidates, who avoided overt efforts to court black support in order to avoid losing white backing, were hurt by declines in black voter turnout. For example, in 1984, Walter Mondale assiduously courted black support and, for his trouble, was abandoned by southern white Democrats. In 1988, Michael Dukakis carefully avoided too close an association with blacks and was punished by a steep decline in black-voter turnout.

Thus, liberal activism and civil rights combined to weaken the Democratic Party in national presidential elections. From 1968 onward, the Republicans moved with alacrity to take advantage of this weakness. Republican presidential candidates developed a number of issues and symbols designed to make the point that the Democrats were too liberal and too eager to appease blacks at the expense of white voters. Beginning in 1968, Republicans emphasized a "southern strategy," consisting of opposition to school busing to achieve racial integration and resistance to affirmative action programs.

At the same time, Republicans devised a number of issues and positions designed to distinguish their candidates from what they declared to be the excessive liberalism of the Democrats. These included support for school prayer and opposition to abortion, advocacy of sharp cuts in corporate taxes and the tax rates of middle- and upper-income voters, a watering down of consumer and environmental regulatory programs, efforts to reduce crime and increase public safety, and increased spending on national defense. During the Reagan and Bush presidencies, taxes were cut, defense spending increased, federal regulatory efforts reduced, support for civil rights programs curtailed, and at least token efforts were made on behalf of restricting abortion and reintroducing prayer in the public schools.

These Republican appeals and programs were quite successful in presidential elections. Southern and some northern blue-collar voters were drawn to the Republicans' positions on issues of race. Socially conservative and religious voters were energized and mobilized in large numbers by the Republicans' strong oppositi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- About the Editors arid Contributors

- Tables and Figures

- Preface to the Third Edition

- 1 HOW DID THE 1994 ELECTION MATTER?

- 2 PUBLIC POLICY AND ELECTIONS

- 3 IDEOLOGY AND ELECTIONS

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Do Elections Matter? by Benjamin Ginsberg,Alan Stone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.