- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Media and Power in Post-Soviet Russia

About this book

This book describes the rise of independent mass media in Russia, from the loosening of censorship under Gorbachev's policy of glasnost to the proliferation of independent newspapers and the rise of media barons during the Yeltsin years. The role of the Internet, the impact of the 1998 financial crisis, the succession of Putin, and the effort to reimpose central power over privately controlled media empires mark the end of the first decade of a Russian free press. Throughout the book, there is a focus on the close intermingling of political power and media power, as the propaganda function of the press in fact never disappeared, but rather has been harnessed to multiple and conflicting ideological interests. More than a guide to the volatile Russian media scene and its players, Media and Power in Post-Soviet Russia poses questions of importance and relevance in any functioning democracy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Media and Power in Post-Soviet Russia by Ivan Zassoursky,Ivan Ivanovich Zassoursky in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Word and Deed

Politicization of the Mass Media

It cannot be said that the ruling apparatus of the USSR was unaware of the problems of the Soviet economy. The numerous reforms that were implemented under successive general secretaries of the Communist Party were always intended to reduce the degree to which the USSR lagged behind the capitalist countries.

At the April 1985 plenum meeting of the CPSU Central Committee, a new general secretary, Mikhail S. Gorbachev, put forth his strategy for sweeping change. In one account:

The key word of the reform strategy was “acceleration.” Seized upon immediately by the party propaganda organs and the mass media, it was repeated like an incantation. Everything had to be “accelerated” Gorbachev-style: production, the social sphere, the activity of the party organs, and most importantly, scientific and technological progress. Eventually, “glasnost” and “perestroika” were added to the strategic concepts. Glasnost meant revealing all the shortcomings that were hindering acceleration, and the criticism and self-criticism of the executive “from top to bottom.” Perestroika involved making structural and organizational changes to the economic, social, and political mechanisms, and also to the ideology, with the aim of achieving the same acceleration of social development. Gradually, however, as it became apparent that “acceleration” was not occurring, the stress came to be placed on “perestroika,” and it was this word that came to symbolize Gorbachev’s policies.1

In his book Glasnost and Soviet Television, Reino Paasilinna, the former head of the Finnish television and radio broadcasting corporation, explains how events unfolded in the late 1980s, and the role that glasnost played in the overall scheme of the reforms. He also examines the new role that television came to play in society as a result of these policies.

Glasnost at first was not a goal in its own right, but a tool for the democratization and political reforms that were supposed to strengthen the socialist system in the USSR. A freed-up (but still controlled) press was in essence the only reliable ally Gorbachev possessed in his struggle with conservative forces in the party apparatus. Television played a special role. Gorbachev was the first Soviet politician to understand fully the power of this medium as a political weapon and a means of creating a personal image—a power that would allow him to circumvent the party hierarchy and appeal directly to the country’s citizens. According to Paasilinna, Gorbachev’s awareness of the possibilities of television was apparent in everything, right down to small details. Noticing a camera in the hall, for example, Gorbachev would orient himself carefully toward it—a skill acquired by politicians throughout the world.

The significance of television emerged during the broadcasts of the proceedings of the Congress of People’s Deputies in the late 1980s. The first sitting of the congress became a huge soap opera that held the country spellbound to such an extent that the streets were emptied. But unlike the Latin American television serials they were competing with, the direct broadcasts of political events, along with a stream of documentary and artistic films on the crimes of communism, helped to politicize the masses:

Television was discovered to have a power whose existence no one had suspected, or perhaps, in which no one had believed. … A unique dethroning of political officials took place on the television screen. No important historical events or individuals, nor the party, nor the system, nor even the most carefully fostered beliefs withstood the gaze of public opinion; everything was blown apart or annihilated. People learned about the mechanisms of power, which had been kept in such stringent secrecy. Earlier, changes of such scope would have been impossible without physical violence, but now television became the nation’s judge.2

During his 1990 election campaign, Boris Yeltsin enjoyed the support of several print publications and of Leningrad television. It was Leningrad television (which could be viewed in Moscow with the help of an indoor antenna) that, for example, broadcast footage of the dispersing of a demonstration in Tbilisi, in the Georgian Republic, and the storming of the television center in Vilnius, Lithuania, where the station, headed by a committee set up by local officials, tried to maintain an anti-Moscow position. In the winter of 1990–91, soon after Yeltsin’s victory in the Russian Republic’s first presidential election, the Russian government established its own television system, which began news broadcasts in May 1991.

During the 1991 putsch, Russian television broadcast news programs that reflected the positions of the legitimate government. This was also the case with the CNN broadcasts, which were retransmitted over the Russian state television channel. The other channels were controlled by the putschists, but their GKChP, the “emergency” committee formed by the Soviet vice-president and leaders of the Communist Party hierarchy, failed to make use of the news potential at its disposal.

The committee was thus unable to find a way out of the contradiction between the need to impose its control over flows of information, and the need to provide people with information about its goals in order to gain their support. Without the support of journalists, the putschists appeared to the public like monsters. Throughout the day on August 19, 1991, after all the publications that could be considered part of the “democratic press” had been shut down, Russian television broadcast the ballet Swan Lake and symphonic music. For citizens used to reading between the lines, this in itself was a sign of trouble. To keep society informed, the GKChP issued a short communiqué that was read over the radio by announcers and published in pro-government newspapers. A press conference was also held, to which journalists from the suppressed publications were, inexplicably, invited. Moreover, the press conference was broadcast live, with the result that it turned into a real-time drama. The journalists accused the top-ranking hierarchs of carrying out a coup d’état. The hands of Soviet vice-president Gennady Yanaev trembled constantly, betraying the putschist’s extreme nervousness and lack of self-confidence. Going live to air (a recording was later rebroadcast with the most serious blunders edited out), the press conference to a large degree determined the attitude that society adopted toward the GKChP. Even people who in principle supported the idea of strengthening the Soviet regime and imposing order were obliged to recognize that the GKChP was not the force that could bring this about.

Paasilinna’s book Glasnost and Soviet Television describes how television affects an audience compared with the print media. Television exercises a profound emotional (and irrational) attraction on the viewer, acting with almost hypnotic power. This is illustrated by the popularity throughout the USSR of the psychics Kashpirovsky and Chumak (the first “conducted sessions” on television; the other “charged water” with healing power). For several years, these two had great success using their reputed extrasensory powers to cure viewers of any imaginable illness, and regularly put their huge audiences into trances. It could even be said that the enthusiasm of state television for curative hypnosis, like its purchases of Mexican television serials,3 represented desperate attempts by the directors of State Television and Radio to direct the politically destabilizing impact of television into comparatively safe channels.

At the time, fortunately or otherwise, this attempt failed. But it is now succeeding.4

The Newspaper as an Ideological Space

The Soviet propaganda system was based mainly on the use of two media, newspapers and radio. Movies were added later. Russia in the nineteenth century was a book-reading culture, but the ideology of the revolution was born primarily in newspaper polemics, against the backdrop—as Marshall McLuhan noted in Understanding Media5—of the oral culture still prevailing in the illiterate provinces.

Every medium has its own peculiarities that aid in affirming one or another modality of perception. While Christianity and other great religions are founded on manuscript texts, and the movements of the Reformation and the logical reductionism of Descartes on the printing press, newspapers are linked to mass industrial society, and to the epoch of the rise of nationalism and of the great ideologies. The newspaper page is ideally suited to schematic exposition and publicistic simplifications, which have always aided the propagation of ideas among the mass public. At the same time, the mosaic of articles creates a sense of the representation of reality due to the range of subjects covered.

In all Soviet-era textbooks, authors always stressed the importance of newspapers, which served as the foundation and the primary information source of the propaganda system. Radio performed a special function in the everyday organization of reality around rituals, whose planning and direction took place in a centralized fashion. Until the reformist 1980s, for example, radio programs began at 6 a.m., and in many hotels, hostels, communal apartments, and even residential complexes the radio could not be turned off; it was as inescapable as the factory whistle.6 In apartments, the radio could be turned off, but the apparatus itself had the character of an obligatory listening-post, usually with three programs. Until the advent of transistor receivers, and even for some time afterward, there was no possibility of listening to other stations. The broadcasts ended at midnight with the playing of the Soviet anthem. Of course, there was also Radio Mayak, broadcasting on the medium-wave band, but on the whole radio broadcasting had a compulsory quality.

Cinematography in the USSR underwent a prolonged evolution from the experimental-propagandist school of Vertov, Dovzhenko, and Kuleshov early in the century to a triumphant “golden age” under Stalin. The epoch of totalitarianism began with musicals promising the fulfillment of the Soviet dream and a happy life in general, before moving on during the war to historical epics (Alexander Nevsky and Ivan the Terrible). Following the war came more complex films like The Cranes are Flying and the so-called old cinema films, which to a degree retained the triumphalist note of their prewar counterparts. Passing through heroicepic, triumphal, and popular phases of development, the cinema approximated the complex worldview of the urban middle layers in the USSR. Its development far outstripped that of Soviet television, not to mention the newspapers, frozen in their monumental forms.

In the second half of the century, books and films purely for entertainment were permitted, while newspapers were not only censored, but served as a tool for the propagation of an ideologized reality to which, in everyday life, radio and television lent formal shape. Radio and television differed little from one another in this respect. In the Soviet media system, television (which fortunately was not interactive as Orwell imagined it) in essence became something like radio with pictures: The same morning exercise drill could now be seen, with a person demonstrating the exercises. After the death of a state leader, just as the radio played symphonic music, the television channels showed ballet programs. Radio plays became television dramas, and so forth. The live picture did, of course, have its strengths—as when the program “International Panorama” showed footage of life in war-torn Lebanon or on the streets of Western cities. In many ways it was television that was responsible for creating the magical aura that surrounded anything foreign. To inhabitants of the USSR, the modern Western urban space seemed enticing and alluring. Compared with the wholesome dullness of Soviet reality, the neon advertising on the streets and the interior of a bar created a sense of danger and adventure—an atmosphere so popular that attempts were often made to counterfeit it. For example, in footage of the Baltic republics filmed to order for television, Riga and Tallinn became showpieces of “Western life.”

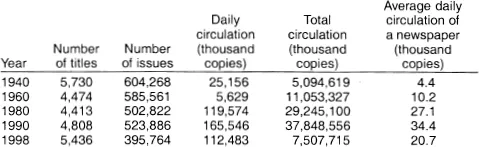

Table 1.1

Circulation of Newspapers in Russia

Circulation of Newspapers in Russia

Source: Yelena Vartanova, “Media in Post-Soviet Russia: Shifts in Structures and Access to Contents, paper presented at conference” (Singapore: IAMCR conference, 2000).

Small pleasures also awaited newspaper readers, who sometimes encountered features written in good literary style.7 Nevertheless, the function of mass “propagandist, agitator, and organizer,” which Lenin prescribed for the party press, held sway over the newspaper industry.

Newspapers, in fact, were the most favorable ambient medium for Soviet ideology (see Table 1.1 for details), and every publication that did not break out of this mold grew rigid, turning into its own monument, its clumsy, conventional ideologies recalling the tombs of unknown soldiers and the statues of Lenin with outstretched arm that were scattered across the urban landscape. It is not surprising that conceptualist artists found in newspapers ideal material for their compositions. Shifting the grey newspaper columns was the equivalent of moving slabs of concrete; breaking up the rigid ideological language of the party documents that often occupied more than half of the space in newspapers was tantamount to committing an outrage against the social system. Only falling readership, and the influence throughout the 1990s of changing “central” newspapers (communist, democratic, and later commercial), would put an end to ideological reality, and to the dream of the public sphere at the same time. Along with the epoch of television, the era of the political spectacle had dawned in Russia.

Soviet newspapers, radio, and television were divorced from reality in the same way as, and to a significantly greater degree than, cinematography or the book publishing industry. In the case of radio and television, however, this abyss was somewhat hidden by the fact that, although these media addressed their audience in a didactic tone, individuals ultimately could ignore them and construct their daily lives differently. They might watch only such piquant offerings as “Travelers’ Club,” “In the World of Animals,” or “Connoisseurs’ Club,” or read an interesting feature or literary essay in an otherwise boring newspaper.

The pages of the newspapers served as the main arena for instilling ideology in mass consciousness both directly and indirectly via the system of local party committees, including the base-level organizations in the enterprises. The real propagandist unit in the Soviet Union was not so much the mass media per se, but the meeting, at which a representative of the party’s ideological apparatus was invariably present. Or, if the meeting was too petty and routine, there was someone in attendance who assumed this role. As a rule, this person was the real or informal leader of the collective, or someone who was interested in gaining promotion, to which social activism was considered a sure path. The modern generation of managers, represented by former prime minister Sergei Kirienko, Mikhail Khodorkovsky (from Menatep Bank), and many of the heads of financial-industrial groups, advertising companies, and personnel consultancies, are former members of the Communist Party’s youth organization, the Komsomol, who began their careers with such activities.

Indeed, the Soviet regime was extremely garrulous, and sought to accompany its functioning with a lengthy and strictly hierarchical process of linguistic brainwashing (local committee, trade union committee, pioneer troop, the Komsomol, and party meetings of the class, group, school, college, plant, region, city, province, and republic—a multitude of pyramids where people were required to listen and speak). For all this, however, the real process of regulation proceeded on other, prelinguistic levels (the question of which levels these were is a separate one). If this had not been so, why would the Soviet re...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables and Figure

- Preface: A Decade of Freedom

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Word and Deed

- 2. The Case of Nezavisimaya Gazeta

- 3. The “Mediatization” of Politics

- 4. Reconstructing Russia

- 5. The Internet in Russia

- 6. The Media System

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index