eBook - ePub

Native Americans Before 1492

Moundbuilding Realms of the Mississippian Woodlands

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Native Americans Before 1492

Moundbuilding Realms of the Mississippian Woodlands

About this book

The pre-Columbian culture of the Mississippi woodlands has received surprisingly little attention from historians. Studying this culture, which was in many respects highly advanced, opens an entirely new perspective on what we are used to thinking of as "American" history. This essay by a distinguished historian and teacher is aimed at world history classes and other classes that cover the Americas before the arrival of the Europeans.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Native Americans Before 1492 by Lynda N. Shaffer,Thomas Reilly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction

Only two hundred years ago, in the woodlands of Eastern North America, there were tens of thousands of large earthen mounds, all of which had been built by Native Americans. They were impressive structures. Visitors who saw them were amazed by the size of many, by their number, and by the intricacy of their design.1 Yet the significance of these earthworks, indeed, their very existence, is one of the best kept secrets of American history. Even the people who now live on or beside the mound sites are more likely to be familiar with the Native American past of Mexico, the Andes, or the U.S. Southwest than with the heritage of their own region.

Before 1492, moundbuilding centers in Eastern North America could be found from the Great Lakes region in the north to the Gulf of Mexico coast in the south, from the eastern portions of the Great Plains to the Appalachian Mountains. They were built over a period of roughly four thousand years. Banana Bayou, one of the earliest earthen mound sites so far discovered, is located on Avery Island in Iberia Parish, on the Louisiana coast, and has been dated tentatively to 2490 B.C.2 The latest sites date from sometime around A.D. 1700.

Two hundred years ago almost all the mounds were still safely outside the bounds of the English-speaking settler colonies. Until about 1800, these colonies were generally confined to the Atlantic seaboard, east of the Appalachians. Thereafter, the number of mounds was reduced as waves of settlers from the east, continually reinforced by a flood of European immigrants, poured over the Appalachian Mountains and began plowing them down. In the twentieth century the mounds have been assaulted not only by farmers but also by vandals seeking valuable artifacts and highway-builders who have bulldozed their way through many, if not most sites. Nevertheless, a great many mounds still stand.

On occasion, the European-Americans who came upon the mounds and were amazed by them had the wisdom to ask the local Native American peoples about them. In Illinois in 1778, for example, Chief Baptist of the Kaskaskias was approached by a group of American Revolutionary War soldiers led by George Rogers Clark. They asked Chief Baptist about elaborate earthworks that they had seen near the Mississippi. The earthworks, he answered, were the outer fortifications of an old palace. It had belonged to the ancestors of the Native Americans when they had "covered the whole," when they had had large towns and been "as numerous as trees in the woods."3

Many of the newcomers, however, were unwilling to believe that Native Americans could have built such imposing structures and felt it necessary to concoct fantastic theories about their origins. In the nineteenth century, various people argued that the mounds had been built by the Lost Tribes of Israel, or the Vikings, or sixteenth-century Spanish explorers. And in the twentieth century, Erich von Daniken's Chariots of the Gods has attributed the mounds to creatures from outer space.4

But Chief Baptist knew whereof he spoke. Indeed, there had been a time when Native Americans towns and villages did cover many of the river valleys of Eastern North America. Although modem demographers might not agree that people were as numerous as the trees, one can say that the Native Americans numbered in the millions. Although for many years the pre-European contact population of North America north of the Rio Grande was said to be only about two million, recent scholarship indicates that this figure is a gross underestimate. In 1983 Henry F. Dobyns published an estimate of eighteen million, a figure that remains controversial. Nevertheless, the estimates of others do seem to be climbing upward toward this mark. Two important studies came out in 1987, one estimating more than seven million and another estimating a population of about twelve million. The latter, based upon settlement patterns revealed by archaeological explorations, tends to support Dobyns's assumptions and methods, even though its author concludes with a lower estimate.5

Both archaeological evidence and explorers' accounts suggest that a large part of this population was concentrated within the moundbuilding region of Eastern North America. These sources also indicate that the mounds marked the centers of political and economic networks. Ceremonial goods and elite burials are concentrated at these sites, and so was military power. Archaeologists refer to the people who ruled from these centers as "paramount chiefs." They were the heads of alliance networks, possibly because of their prestige or control of scarce resources, or because of their superior military might. And through these networks they could command the loyalty and often the tribute of less powerful chiefs and the peoples they led. Paramount chiefs encountered by the Spanish and French were known as "Great Suns," and, just as Chief Baptist suggested, they lived in palaces—in large and elaborately decorated wooden structures—which were built on the top of high platform mounds. Specially designated groups known as "noble allies" and "honored people" also resided at these centers, and so did much larger numbers of "commoners"—farmers whose fields were nearby, hunters, traders, and artisans.

It is also clear from goods found in the graves of elite persons that moundbuilding centers participated in exchange networks that eventually grew to almost continental proportions. Products from far-off places can be found at many sites, but they tend to be concentrated at the largest centers. Some of the more notable items on a long list that appear to have enjoyed wide circulation include Rocky Mountain stones used to make cutting edges, minerals from the upper reaches of the Mississippi used to make paint pigments, marine shells from Florida, copper from the Great Lakes, stone pipes from the Ohio River valley, and mica from southern Appalachia.

The construction of moundbuilding centers can be divided into three separate epochs. During the first epoch, which took place during the Late Archaic Period (ca. 1500-700 B.C.), such activity was confined to the Lower Mississippi River valley and adjacent areas. The largest center, a site that archaeologists call Poverty Point, was a few miles west of the Mississippi River in northeastern Louisiana. A second moundbutlding epoch took place during what is known either as the Woodlands Period or the Adena-Hopewell Period (ca. 500 B.C. to A.D. 400). It was during this epoch, when the most important centers were concentrated in southern Ohio on tributaries that flow south into the Ohio River, that the construction of moundbuilding centers first spread throughout much of the Eastern Woodlands.

A third moundbuilding epoch (ca. A.D. 700-1700), which archaeolo

Chronology of the Moundbuilding Region

| Ice Age Hunters and Gatherers | 12,0000-8000 B.C.* | |

| Extinction of Ice Age animals (9000 B.C.) | ||

| Early Archaic Period | 8000-6000 B.C. | |

| Localization, use of atlatl | ||

| Middle Archaic Period | 6000-3000 B.C. | |

| Sedentary habits emerge | ||

| Late Archaic Period | 3000-500 B.C. | |

| Population increase, long-distance exchange | ||

| Domestication of indigenous plants | ||

| Elite burials, copper in use in north | ||

| Pottery in some southern locales | ||

| First Moundbuilding Epoch (Late Archaic Period) | 1500-700 B.C. | |

| Poverty Point Cultural Area | ||

| Lower Mississippi Valley | ||

| Second Moundbuilding Epoch (Woodlands Period) | 500 B.C.-A.D. 400 | |

| Adena-Hopewell Period | ||

| Adena | 500-100 B.C. | |

| Ohio River valley | ||

| Hopewell | 200 B.C.-A.D. 400 | |

| Hopewellian sites throughout moundbuilding region | ||

| Regionwide integration of exchange networks | ||

| Pottery and corn found throughout region | ||

| Increased use of indigenous domesticates | ||

| Spread of bow and arrow (A.D. 300-600) | ||

| Third Moundbuilding Epoch | A.D. 700-1731 | |

| The Mississippian Period | ||

| Palisaded towns, hoes, ball courts | ||

| Reliance upon corn, beans, and other crops | ||

| Cahokia | A.D. 700-1250 | |

| Major Spanish invasions | A.D. 1513-1543 | |

| Postcontact survivals | A.D. 1550-1731 | |

| French defeat Natchez | A.D. 1731 | |

* Most of the dates in this chronology are approximations. Especially with regard to the Archaic Period, many are based upon limited data and are subject to change as more data are analyzed and new findings reported. Although there is general agreement regarding this chronology, some scholars would use slightly different dates to define the various periods.

gists refer to as the Mississippian, witnessed the rise of Cahokia, a paramount center located on the Mississippi River, near what is now East St. Louis, Illinois. Between A.D. 900 and 1200, it was many times larger than any other center in Eastern North America. After its decline, a number of more modest centers flourished. Some survived the arrival of the Spanish, and at least one, that of the Natchez in what is now western Mississippi, survived into the eighteenth century.

Almost all of the moundbuilding centers were located withm the Eastern Woodlands. This temperate, but relatively southern, forested region provided an ecological setting unlike any other in the world. There are no extensive forests in the temperate zone of the Southern Hemisphere, and all but one in the Northern Hemisphere are much further north. (Only the forests on the steep mountainsides of China's Yangzi River drainage share the Eastern Woodlands' southern temperate position.) Florida is at the same latitude as the Sahara Desert, and even Minnesota and Wisconsin, places usually thought of as northern, are, in fact, at the same latitude as Italy.

It should be emphasized, however, that the moundbuilding region was essentially a human creation—the result of cultural continuities that emerged from ceremonial and exchange networks—and that no single feature of the North American landscape, not even the Eastern Woodlands, shares with it exactly the same boundaries. The Woodlands, for example, extend north of the Great Lakes for a considerable distance and east of the Appalachian Mountains all the way to the Atlantic Ocean. But almost all moundbuilding centers were located south of the Great Lakes, and except in the Southeast (in the Carolinas, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida), almost all were located west of the Appalachian Mountains. It was only during the second epoch, when sites in southern Ohio were predominant, that centers could be found within the Lake Ontario drainage, in what is now New York State and the southeastern part of Ontario, Canada. On the other hand, during the third epoch when the largest center was at the mouth of the Missouri River, they extended westward along this river and its tributaries onto the Great Plains, well outside the bounds of the Woodlands.

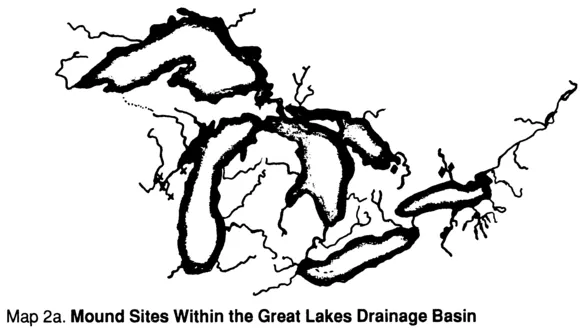

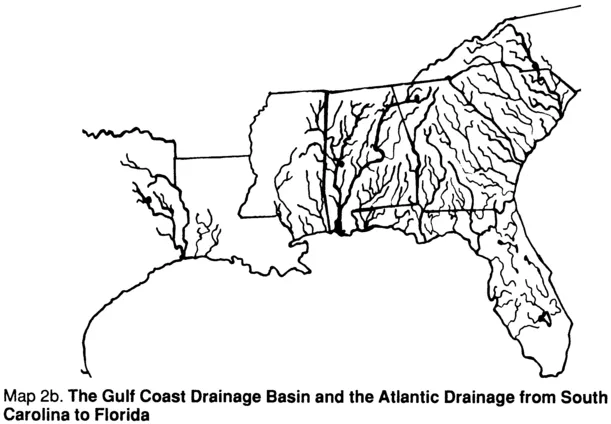

Perhaps the best way to define the boundaries of the moundbuilding region would be to identify the four riverine drainage basins that it included. (See Map 1.) The largest part of the region was the eastern two-thirds of the Mississippi River drainage, from present-day Nebraska in the west to New York in the east, and from Minnesota in the north to Louisiana in the south. The region's second largest part was the Gulf Coast drainage basin from the Neches River in eastern Texas to the northern edge of the Everglades in Florida. These two basins were by far the largest and most important parts of the region. In addition, it included two adjacent areas. One was the southernmost part of the Atlantic Ocean drainage, from the Pee Dee River in North Carolina to southern Florida, and the other was the Lake Ontario drainage, which included much of New York and a small part of Ontario. (See Maps 2a and 2b.)

Map 1. The Moundbuilding Region. The abbreviations MS, MO, AR, OH, and TN identify the Mississippi River and four of its tributaries, the Missouri, Arkansas, Ohio, and Tennessee rivers. The asterisks mark the principal centers of moundbuilding during each of the three epochs: I. Poverty Point (ca. 1500 to 700 B.C.); II. Adena-Hopewell (ca. 500 B.C. to A.D. 400); III. Mississippian (ca. A.D. 700 to 1731).

Unlike the ocean-linked networks of interaction that developed in Eastern North America after the Europeans came, those before 1492

Maps 2a and 2b, Parts of the Moundbuilding Region Outside the Mississippi River Drainage. For the most part, the moundbuilding region was located within the Mississippi River drainage basin. The only parts of the region that lay outside this basin were the Gulf Coast drainage basin from eastern Texas to Florida, the Atlantic drainage from South Carolina to Florida, and some locales within the Great Lakes drainage basi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Maps and Other Illustrations

- Foreword

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Archaic Context from Which Moundbuilding Emerged

- 3 Poverty Point, the First Moundbuilding Epoch

- 4 Adena-Hopewell, the Second Moundbuilding Epoch

- 5 Cahokia and Other Mississippian Period Centers, the Third Moundbuilding Epoch

- 6 Subregions, Outposts, and the Decline of Cahokia

- 7 Conclusion

- For Further Reading

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index