![]()

Part I

Real and Imagined Spaces

![]()

1

“Funny Men and Charming Girls”1

Revue and the Theatrical Landscape of 1914–1918

Andrew Maunder

The established view of First World War theatre in Britain is that it responded to the declaration of war on 4 August 1914 with a flood of crude propaganda plays and never really recovered. Although historians have developed a more sympathetic approach to wartime entertainment, recognizing its importance to combatant and civilian life, much of what was shown remains ignored. A case in point is revue, a pre-war package of topical sketches, comedians and chorus girls which achieved mass appeal after 1914.2 If revue remains neglected, it is not because of a shortage of evidence but because the form itself remains denigrated; silly, superficial, commercial, it seems to represent much that is antithetical to “serious” works produced during the conflict—the writings of trench poets, for example. Yet one of the most famous indictments in Siegfried Sassoon’s poem “‘Blighters’” (1917) was prompted by watching Fall In! at the Liverpool Hippodrome in December 1916. The poem’s description of the show’s “prancing/Ranks of harlots,” the audience’s “cackle” and Sassoon’s wish for a tank to come “lurching” in and crush this unfeeling display, is often used to highlight revue’s questionable attractions, not least its apparently callous disregard for the realities of war.3

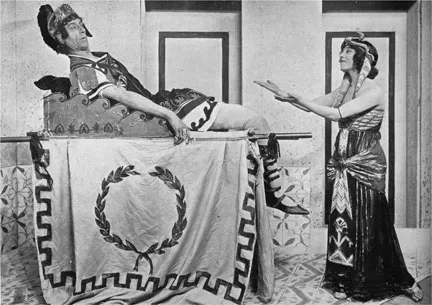

Historians of wartime culture have tended to follow Sassoon, adopting a disparaging stance towards an ephemeral form of entertainment that sought public approval and a “fast buck.” Certainly it is the disposable songs which stand out when we look at a show like the Charles Cochran-produced Pell Mell (1916) (Figure 1.1) which ran for 300 performances at London’s Ambassadors theatre with titles including “I’m a Musical Comedy Bus’ness Man”, and “I’d Like to Know what Cleopatra Did.” Producers like Cochran have been accused of putting serious plays “out of action” during the war, putting on puerile comic sketches that exploited vulnerable soldiers on leave who were happy because they “were no longer under fire” and ready to be pleased by anything, as George Bernard Shaw put it.4

Along with Sassoon, Shaw’s comments offer the best-known disapproval of populist wartime theatre but he did at least recognise its appeal. In 1919 Shaw recalled how London’s theatres were “crowded every night with thousands of soldiers on leave [who] were not seasoned London playgoers,” often “accompanied by damsels (called flappers)” who together drove the fare on offer.5 Another eyewitness, W. Macqueen-Pope, noted soldiers’ families including parents “who had never been inside a theatre before, thinking them sinful places, went with their sons and found they were really very enjoyable.”6 Writing in 1918, George Street noted how these spaces also attracted the “great many war-workers living in London.”7 Many of these new theatregoers were women who now had their own money to spend.

Figure 1.1 Antony (Leon Morton) and Cleopatra (Dorothy Minto), Pell Mell, 1916.

These observers sounded common themes: the theatre world changing; new audiences entering unfamiliar surroundings. But they—and many others—also highlighted the extent to which London was serving as a “clearing house for the Western Front” encouraging a boom in theatre attendance.8 A report written in November 1915 by B.W. Findon summarised how leave trains:

discharged some three thousand officers and men per day, and weekend leave from the various camps in the country has brought to London hundreds of young officers who are bent on making the most of their Friday and Saturday. A good percentage of these… would have been differently occupied in the days before the war… but the man who has endured the monotony and mud of camp life for several weeks naturally seeks the delights of urban life.9

With no organised activities during leave, theatres became places for these men to find diversion. Two years later, revue producer Albert de Courville claimed that 75% of audiences were now soldiers of all ranks.10 Among them was nineteen-year-old Australian Jack Duffell whose experience of leave at “home” in 1917 included two days in London (“civilization”), where he and another soldier saw the musical, High Jinks, which they “enjoyed immensely.”11 A British officer, Lieutenant F.H. Ennor, whose rank entitled him to more leave than “ordinary” soldiers, spent evenings similarly engaged. In February 1917 he saw the revues Three Cheers and Zig Zag, as well as the exotic musical Chu Chin Chow. This was followed by The Bing Girls in March, Zig Zag again and Smile before he was sent out to the Front.12 Lieutenant Wilfred Owen’s last recorded theatre trip in June 1918 was to see The Bing Boys on Broadway, the (mis)adventures of two British country bumpkin brothers in America.13

Although other entertainment held its appeal, this chapter will argue for the importance of wartime revue and highlight some of the ways in which revues were generated and played out. When J.M. Barrie’s Rosy Rapture, starring the exotic French danseuse, Gaby Deslys, and featuring a kinema picture of chapters in the life of a young baby and a vicious lampoon of national treasure, Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, premiered in March 1915, at least one in the Duke of York’s Theatre audience—H.M. Walbrook—saw it as a symptom of cultural decline, or at least that the world really was “beginning to turn upside down.”14 As will be seen, many of Walbrook’s contemporaries agreed with him. Others, however, saw revues as important outlets for escapism and sociability as well as supplying a kind of black or ironic humour, which appealed to the wartime population, particularly servicemen. More recently James Ross Moore has suggested that revues should be seen as the period’s most modern form of musical theatre: escapist certainly, but also “vital, influential and innovative,” at the same time as being capable of offering trenchant social commentary.15 Thus although revues have often been dismissed as theatrical froth they occupied a more complex theatrical space than we have traditionally been led to believe, involving different cultural fields and enterprises and a variety of subject positions.

A Theatre for the War

Most contemporary accounts agree that from autumn 1914 the appetite for revue became “rampant.”16 The form predated the war with producers and performers such as George Grossmith, Harry Pelissier and Charles Cochran, importing elements from France (where revue was well-established) and, after the advent of ragtime and syncopated music, the United States.17 Notable pre-war successes included Kill that Fly (1912) and Hullo Tango! (1913). The war, however, represented a watershed in revue’s popularity. Whilst “serious” plays such as Edward Thurston’s shell-shock drama The Cost (1914) closed early, revue began to flourish—“the only theatrical entertainment for which there is still a huge public,” as a writer for Tatler noted in June 1915.18 In The Other Theatre (1947), Norman Marshall suggested that this transformation in the theatrical landscape coincided with the wartime decline of the middle-aged Edwardian actor-managers such as Herbert Beerbohm Tree, George Alexander and Fred Terry, and the purchase of theatres by uncouth “business magnates” who, by staging revues and musicals, made “money out of the completely uncritical war-time audience.” Marshall felt these men viewed their theatrical properties as “impersonally” as their other holdings—“factories, the hotels, the chains of shops, the blocks of flats” with no interest in the theatre as art.19 His interpretation says a lot about how revue has come to be positioned; promoters are judged as obscure or irrelevant and content as crude and opportunistic, yet the genre cannot be completely ignored.

More recently, Gordon Williams has found more of interest in the ways in which two forms of wartime revue—the spectacular and the intimate—overtook musical comedy as the main competitor for audiences for plays, yet became classed as “low” rather than “high” culture.20 This label proved difficult to shake off. In 1917 Tatler described revues as “pantomimes without the fairytale.”21 While, on the one hand, a reference to the idea that a revue’s task was to offer spectacular scenes and light-hearted escapism, on the other, it is a comment designed to suggest dumbing down. By this time the cultural landscape had altered to include such names as the aforementioned Charles Cochran (1872–1951), Alfred Butt (1878–1962), André Charlot (1882–1956) and Albert de Courville (1887–1960), well-known and reliable money-spinners who developed revue into a speciality, bringing good business to the theatres in which they had a financial interest, enabling them to keep afloat in quiet periods. As has been noted, these were “new types” of theatre professionals. As “producers” (a new term in 1914) they competed with each other and with the actor managers reliant on wartime revivals of costume dramas such as The Scarlet Pimpernel or Sweet Nell of Old Drury which audiences were believed to find comforting and uplifting but which were also old-fashioned.

The sense of the war sweeping “legitimate” drama away beneath a deluge of revues is apparent in the testimonies of theatrical critics and other theatregoers of the time. Some had expected that the war would create a new brand of patriotic drama to inspire the nation but they were disappointed. As the Bystander complained in March 1915, it was revues which were

positively pouring on, and without even a particle of a pretence of seriousness of purpose about them… The purifying effect of war we all talked so much about—where is it? The same sort of chorus girls—and men—are taking the middle of the stage again… and any night of the week the Britisher whose country is fighting a very hard fight for its very existence, may be seen in his thousands absolutely absorbed in the very last touch in rag-time or the latest undressing act…. Where are the popular dramas and the stage idols of this great crisis in our history? An Irving in Hamlet, a Benson in King Henry V? Not a bit of it. The attractions of the moment are such “features” as Elsie Janis at the Palace.22

Shakespeare, of course, represented the best part of Britain’s cultural heritage, and old prejudices died hard. Nonetheless theatre managers up and down the country encouraged revues, knowing that the form had broad audience appeal. When Herbert Beerbohm Tree was quizzed about the early closure of his revival of Henry IV Part 1 at Britain’s unofficial national theatre, His Majesty’s, in November 1914, he could only say “that even the splendid heroics of Hotspur […] are not so ap...