eBook - ePub

Korea at the Center: Dynamics of Regionalism in Northeast Asia

Dynamics of Regionalism in Northeast Asia

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Korea at the Center: Dynamics of Regionalism in Northeast Asia

Dynamics of Regionalism in Northeast Asia

About this book

The common images of Korea view the peninsula as a long-standing battleground for outside powers and the Cold War's last divided state. But, Korea's location at the very center of Northeast Asia gives it a pivotal role in the economic integration of the region and the dynamic development of its more powerful neighbors. A great wave of economic expansion, driven first by the Japanese miracle and then by the ascent of China, has made South Korea - an economic powerhouse in its own right - the hub of the region once again, a natural corridor for railroads and energy pipelines linking Asiatic Russia to China and Japan. And, over the horizon, an opening of North Korea, with multilateral support, would add another major push toward regional integration. Illuminating the role of the Korean peninsula in three modern historical periods, the eminent international contributors to this volume offer a fresh and stimulating appraisal of Korea as the key to the coalescence of a broad, open Northeast Asian regionalism in the twenty-fifth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Korea at the Center: Dynamics of Regionalism in Northeast Asia by Charles K. Armstrong,Gilbert Rozman,Samuel S. Kim,Stephen Kotkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Imprenditoria. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Competing Visions of Regional Order

Late Nineteenth/Early Twentieth Centuries

Let us begin unconventionally for Northeast Asia, not with China, or even Japan, but with Korea. From about the 1650s until the 1850s, Korea’s real status failed to correspond to its central geographic position. Situated between three larger and more powerful states, it faced not aggression but mostly benign neglect. Having been invaded in the 1590s by a newly integrated Japan that was on its way to a century of extraordinary premodern development—quadrupling of urban population, consolidation and bureaucratization of elites, rapid integration of a national market—Koreans found reassurance that Japan’s new rulers chose a decentralized balance of power and inward-looking posture. In addition, having suffered incursions from a newly expansionist Manchu banner state in 1627 and 1636, Koreans were relieved that once the Manchus had seized imperial power in Beijing, interest in new attacks faded. Even as commerce flourished in China as in Japan, narrowly circumscribed channels to Korea replaced old trade networks. The Chinese concentrated commerce on overland tribute missions, which were reduced to only once a year, or periodic trade fairs even as the Japanese allowed commerce only through monopoly traders confined to the island of Tsushima. Thus, despite being a peninsula defined by open coasts, Korea had little contact with foreign merchant ships. While the royal court in Seoul embraced this relative separation, it endured because Korea’s huge neighbors wanted it that way.

To be sure, there is a longer, different history of the Korean peninsula (a history whose relevance may be growing), whereby Korea had kept a central role in the region for almost a millennium—and had done so even after Japan had retreated from active engagement on the peninsula in 663 and China had abandoned periodic efforts to invade around the same time. But from the seventeenth century, forces of autonomy in each state left little room to connect the region. Certainly the means existed for possible regional integration: Large ships were well known, including Portuguese and Dutch vessels that plied the world’s waters and docked at the few ports open to them; specialized, domestic commerce grew and expanded the range of goods available to exchange; and organized merchant groups amassed ample resources to stretch their operations. Strong states, however, rejected not only opening borders to representatives of European powers but also wide-open contact with their neighbors in East Asia. Attuned to a worldview that privileged perfecting harmonious state–society relations within a single country, they had no guiding thought in favor of welcoming even the Confucian outside world with which they were long familiar.

Matters changed in the nineteenth century, as sudden incorporation of parts of East Asia into the global order became the driving force for the creation of a new regional order. In the 1880s Korea appeared as a vacuum that each of the contending powers feared would be filled by another state. Each state started with the intent to deny anyone else a chance to dominate Korea while working to maintain its independence. China moved first to bolster its position, based on traditional rights, by converting its loose hegemony in 1882 from a ritually hierarchical tribute system to imperial stewardship backed by troops on Korean soil. But China proved too weak to hold what it had long left alone to sustain its influence. Russia, after obtaining the Maritime Zone in a treaty with China, became an active neighbor by building the city of Vladivostok and sending merchant and military ships along Korea’s coast. Yet, Russian influence peaked in 1896–97, as the Korean king desperately sought its assistance. Korean nationalists soon organized in opposition and Russian leaders proved to be willing to cut a deal with Japan in order to get a freer hand in Manchuria. In the event, it was Japan that became the driving force in building on forces of world integration with designs for regional integration. Thus did Korea reemerge as a crossroads of Northeast Asia.

Against this competitive background, visions of a new regional order diverged. While China clung to its Sinocentric order, both Korea and Japan were reconceptualizing this part of the world to give their own countries a certain centrality. Incipient national identities clashed with both the established Chinese civilizational identity and the impending Western worldview on the horizon. In this volume’s chapter by Takashi Inoguchi we are reminded that a conflict with China’s insistence on clinging to a China-centered world order, combined with Korea’s refusal to shift away from a Korea-centered order that tightly limited contact with Japan, drove the new Meiji government in search of a place in the Western-centered order to focus on opening Korea. Inspired by its embrace of the hegemonic global order, Japan joined Russia in striving to reshape the regional order to give it an enduring advantage as the nexus between the two. If officials in Tokyo did not proceed from a strategy for regional control, the “power vacuum in Korea” nevertheless kept inducing them ever deeper into the struggle for such leadership. Cognizant of China’s delayed rethinking of a Sinocentric order that entangled it in peninsular affairs beyond its capacity and Russia’s premature insistence on spheres of influence that overexposed its forces before they had securely established themselves in Northeast Asia, Japan kept ratcheting up expectations for its security role in Korea.

Russian factions, for their part, had differed on how to approach Korea and Northeast China as well. As Alexander Lukin argues in his chapter, the prevailing approach emphasized patience and no further territorial expansion. Although from 1884 there were temptations to become assertive, the position that gained the upper hand was to support Korean independence, first against China and then, more urgently, against Japan. In 1896–97, Korean leaders turned to Russia, leading to extensive involvement but still caution. Yet, military interests, led by officials intent on acquiring a naval base in Korea, decided aggressively to challenge Japan. Koreans had drawn Russia into their power struggles, and then Russians, too, played a large role in drawing Japanese more deeply into Korean politics. In the event, the Japanese, victorious in the Sino-Japanese War and then the Russo-Japanese War, found no obstruction in gaining full control over Korea. The reemergence of Korean centrality ended abruptly with Korea reduced to a colony and Japan growing more assertive in using its toehold there to subject the entire region to its imperial authority.

Simply put, Koreans lacked a unified and consistent strategy that would allow them to steer a path through the diplomatic machinations and oppose the assertion of Japanese hegemony. On the contrary, Korean actions played into that outcome. Hahm Chaibong’s chapter traces a pattern of Koreans seeking saviors and then putting up little resistance when the outside power infringed on national independence, whether orthodox Confucians accepting China’s resident control, the king and a pro-Russian cabinet calling for Russia to exercise dominant influence, or the Enlightenment Party agreeing to Japan’s “Protectorate.” Mostly, Koreans were content to retain the old regional order. Later, some idealized Pan-Asianism, without realizing that this stance allowed Japanese nationalism to rush into the void. But a number of Korean modernizers, as Hahm shows, consciously looked to Japan as a model to lead the way for the entire region.

Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century political and geopolitical changes in the regional order took place against the background of a sharp rise in trade, albeit from a very low starting point, as documented in the chapter by Kirk W. Larsen. By 1883, three treaty ports in Korea had joined the country not only to Western entrepots but also to nearby ports in southwest Japan and northern China. Importantly, Larsen has uncovered dynamism in the Korean economy prior to Japanese involvement. The upshot, though, was that Korean traders and farmers became closely linked to Japan. At the ports of Wonsan and Inchon, Chinese merchants more than held their own for a time. Before long, however, textiles from Japan superseded British goods, strengthening Japan’s hand at the expense of the Chinese merchants. Through integration of trade, transportation, and communications, the Japanese developed an infrastructure conducive to their political control as well as to making this peninsula the bridgehead for further continental economic penetration. Japan defeated China not only militarily but also by utilizing their rapidly modernizing economy to draw Korea’s economy closer. The lessons for all concerned would be bitter.

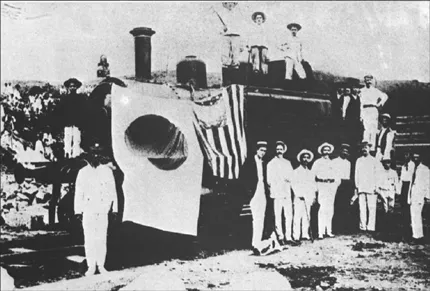

The first railroad in Korea was built as a joint venture between the Japanese and Americans. The Kyongin railroad line was finished in 1896. (Reproduced with permission of Donga Ilbo, Seoul, Korea.)

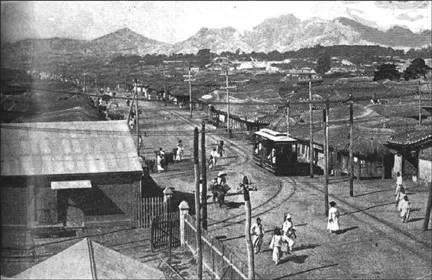

The first streetcar ran in May 1899 after its completion by an American company the prior year. Streetcar is seen coming out of its depot in the East Gate area of Seoul. (Reproduced with permission of Somundang, Seoul, Korea.)

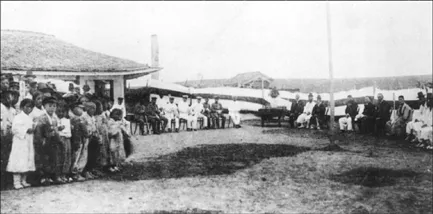

The opening ceremony for Kanto Normal School for Koreans, 1908. Chosenkoku shinkei. (Photograph by Hayashi Buichi; Published by Hayashi, Kameko, Japan.)

Japanese soldiers and border stone marking the boundary between Korea and Kanto, Manchuria. The stele was first erected in 1712. The Japanese finalized the exact location of the boundary with the Chinese in 1909. (Shiho bunko, Japan)

Crossing to China over Yalu River. Majima shashincho (Photographs of Majima). (Sotokufu rinji majima hasyutsujo, Japan)

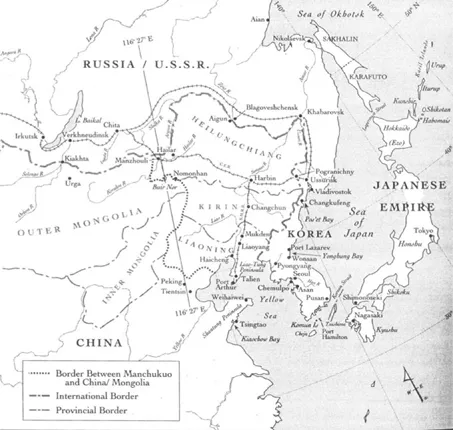

Map of Northeast Asia, 1905–41 (From G. Patrick March, Eastern Destiny: Russia in Asia and the North Pacific. Westport CT: Praeger, 1996. Used with permission of Greenwood Publishing Group.)

1

Korea in Japanese Visions of Regional Order

During the past fifteen hundred years, the Korean peninsula has frequently been at the forefront of Japanese debates about Japan’s place in its region. In particular, two turning points decided Japan’s involvement in East Asia prior to 1945. The first occurred in 663, after the Japanese defeat in southwestern Korea (then called Paekche) forced them to retreat from the continental bridgehead that had been established. With the exception of the invasion of Korea by Hideyoshi at the end of the sixteenth century, this retreat from active involvement on the Asian mainland endured for twelve hundred years, ensuring a level of Japanese autonomy from continental Asia far beyond that of (for example) England from continental Europe.

The second major turning point was Japan’s submission to Commodore Matthew Perry’s coercive naval diplomacy in 1853, obliging Japan to open its ports and country to Western powers. While the seventh-century defeat discouraged Japan from active involvement in Asia, the 1853 “opening” led to Japanese reengagement with the continent. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, competition with other powers for influence over Korea led to a rethinking of Japan’s place in Northeast Asia. Thus, whether Japan has been engaging with or disengaging from mainland Asia, geographic realities and historical connections (good and bad) put Korea at the center of Japan’s interest in the continent.

An Interconnected History

Control over Korea has long had a profound impact on Japan’s fortunes. In the mid-seventh century A.D., the Koguryo kingdom, whose territory spread across Manchuria and northern Korea, engaged in a series of violent conflicts with China’s Sui dynasty and Sui’s successor, the Tang. In 660, Koguryo’s peninsular rival, the Silla kingdom of southeastern Korea, allied with Tang to defeat Koguryo. The combined forces of Silla and Tang then overcame the Paekche-Japan coalition in southwestern Korea in 663, and most of the Korean peninsula was unified under Silla control.1 These regional upheavals led to new power configurations in Silla-dominated Korea and in Yamato-dominated Japan. Strong dynasties in China and even longer-lasting united dynasties in Korea left little scope over the next millennium for Japanese armed intervention on the continent. Instead, advancing from their nucleus of power in the Yamato area, Japanese leaders turned to state-building at home.

Although it is most likely that the ruling elites of Yamato-dominated Japan were direct descendants of Koreans (as indicated by Emperor Akihito’s explicit reference in his official speech made in reply to President Kim Dae Jung during the latter’s state visit to Japan in 1998), the newly consolidating regime in Japan took swift measures at making its separation and distance from the continent solid and enduring and at expanding and consolidating its territory and authority toward northeastern and southwestern Japan, which had been controlled by more “indigenous” peoples. Their new goals were centered on distancing Japan from Sino-centric civilization and creating a separate world order on the Japanese archipelago. This retreat from the continent and subsequent consolidation of the Japanese state appears comparable to England’s retreat from Europe and its subsequent vigorous state formation.2 In fact, however, Japan’s retreat was much greater and longer lasting. Furthermore, Korea’s unity and stability—and its continued close relationship to China—contrasted with the ongoing flux across Europe that invited renewed English participation.

Japan demonstrated its determination to place itself outside the Chinese world order by—among other acts—sending official correspondence to China in the name of the Japanese “emperor” (unlike a proper tributary state such as Korea, which could claim only to have a “king,” implicitly subordinate to the Chinese emperor), and by receiving “tributary” missions from the Korean peninsular states of Silla and Parhae, the latter of which had more or less inherited the territory of Koguryo.3 Through most of the next twelve hundred years—again, with the exception of Hideyoshi’s disastrous expedition to conquer Korea in the late sixteenth century—Japan’s foreign policy doctrine was to keep stable, friendly, and commercially profitable relations with the continent (China and Korea) as long as they remained at arm’s length. Despite Japan’s later receptivity to Confucian teachings, one of the consequences of this distancing was to solidify a civilization gap; even some Western observers, from Arnold Toynbee to Samuel Huntington, have thus drawn a sharp distinction between Japanese and Chinese civilization.4

Commodore Perry’s gunboat diplomacy led quickly to the establishment of a U.S.-Japan Treaty of Amity in 1854.5 Under the circumstances of the mid-nineteenth century, Japan’s conception of world order also made the Western world its principal reference, replacing earlier reference to the Chinese world order. In sharp contrast to the contemporary Korean leader, the Taewongun, who fought and repulsed such Western demands in the 1860s and 1870s, the leaders of Tokugawa Japan, faced with superior force, were realistic enough to recognize that Western power was unconquerable and the trend of Westernization irreversible. Japan could not possibly challenge the Western nations’ predominance in technology, commerce, institutions, and knowledge. What Japan did instead was to create a new regime adaptable to a Western world order. The Meiji Restoration of 1868 was crafted to execute Japan’s fast Westernization while insisting that the Japanese spirit would remain intact (wakon yosai—Japanese spirit, Western technology). “Revitalizing” the Japanese “spirit” had an international as well as a domestic dimension: Leaders were concerned with proving that Japan cou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I. Competing Visions of Regional Order: Late Nineteenth/Early Twentieth Centuries

- Part II. Competing Regional Orders: Colonialism, the Cold War, and Their Legacies

- Part III. Toward a Broad Regionalism?

- Epilogue: Korea, Northeast Asia, and the Long Twentieth Century

- Notes

- About the Editors and Contributors

- Index