Mental Health for Primary Care

A Practical Guide for Non-Specialists

- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

'This book gives a 'bottom-up', practical overview of mental health. I have distilled psychological, biological and sociological background material and siphoned off anything that is not relevant to primary care. I aim to demystify the management of common problems and empower the reader to have a more rewarding and fun time at work and a better ability to cope with the ever-increasing demand and challenge of dealing with multiple physical and mental health issues often brought by a single individual to a time-limited consultation' - Mark Morris.This book provides an up-to-date guide to mental health for primary care workers who are not experts in the field. It is logically structured, providing a clear overview of causal factors before presenting individual conditions in a diagnostic hierarchy. Particular attention is given to areas where there has been a deficit in understanding or training, along with problems that are most frequently encountered and managed in primary care. Meanwhile, a Psychological Tools section introduces solid practical frameworks for managing mental health problems developed from cognitive behaviour therapy, solution-focused and motivational interviewing techniques. A selection of resources for patients is also included. It includes foreword by: Andrew Polmear MA MSc FRCP FRCGP; Former General Practitioner and Senior Research Fellow, Academic Unit of Primary Care, The Trafford Centre, University of Sussex, September 2008.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART ONE

Causation

CHAPTER 1

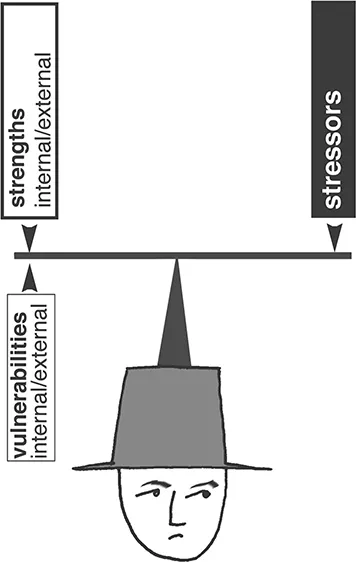

Vulnerability and resilience: personality

GENETICS

BIRTH

EARLY RELATIONSHIPS

Until the age of three: temperament and attachment

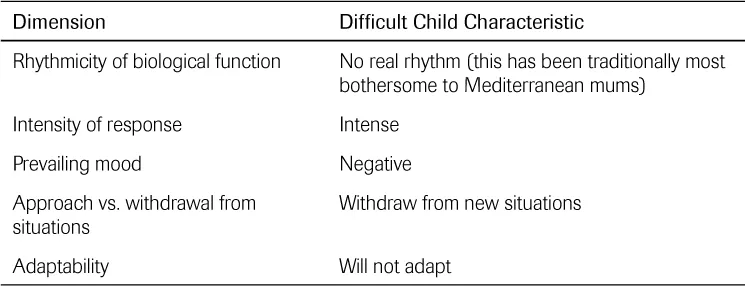

Temperament and ‘goodness of fit’

Attachment theory (Bolby,5 Ainsworth6)

1 Normal attachment formation

2 Abnormal attachment formation

The best test is asking the mother if she feels emotionally close to her child

Parental factors

Child factors

A bit of both

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- About the author

- Acknowledgments

- Background concepts

- Part One Causation

- Part Two Problems

- Part Three Psychological tools

- Part Four Patient resources

- Appendices