Introduction

Three questions related to criminality have vexed civilizations since the dawn of time:

Why do individuals engage in criminal behavior?

How can we prevent criminal behavior?

What do we do with those who commit crime?

Suggested answers have historically reflected a categorical alignment with one of two metaphysical perspectives: That we possess the will to act freely or, conversely, that our actions are predetermined by internal or external factors over which we have limited control. Politics, culture, and science have and continue to coalesce and collide, resulting in theories designed to determine which of these perspectives is more valid, reliable, and relevant to public policy.

Neurocriminology represents a 21st-century response.

It is a response informed by the successes and failures of the answers offered before it.

Whether one believes history is a series of pendulum swings over a relatively unchanging core, or an iterative evolutionary process that inevitably unfolds into the present, a review of some of the dominant criminological theories to date—those of the Pre-Classical Period, the Classical School, the Positivists, Mainstream Criminology, Critical Criminology, and Left Realist and Conservative Criminologies, as well as an example of the biologically based theories of the 21st century—illuminates the influence of politics, science, and culture on crime and crime control. The historic review also suggests the manner in which these factors have and will continue to influence neurocriminology.

The 18th Century and the Classical School

In the 1700s, the will of man replaced the will of God, as the electorate replaced divine sovereignty. In this age of Enlightenment and reason, the Genevean philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau argued that legitimate authority can only be derived from a social contract agreed upon by all citizens for their mutual preservation, rather than through the edicts of a single leader presumed to be sanctioned by God.

The role of religious authority in politics was also challenged by Georges Cuvier’s scientific confirmation of extinction, which contradicted the creationist view of life’s inception and offered a biological basis for existence. Additionally, Thomas Bayes’s theorem of probability—which suggests that the likelihood that something that will occur can be statistically derived by looking at influencing factors—asserted that the universe is logical and malleable, rather than preordained and immutable.

Inventions of the time also reinforced the notion that fate is not predetermined. The period saw the development of the steam engine and the creation of the fabric spinning frame, heralding the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, in which manufacturing replaced manual labor and wider sections of the population had broader professional choices. Reflected in Adam Smith’s publication of The Wealth of Nations, the century saw the rise of capitalism and, concurrently, a newly established and more independent middle class.

Within this context emerged the earliest recognized school of criminology: the Classical School.

Consistent with the rising rationalism within the political, scientific, and cultural sectors during this time, the Classical School proposed that crime was a logical consequence of an unfair system: criminals commit crime as a natural and understandable response to inequity. Preventing and controlling crime, therefore, would result from replacing arbitrary governance with laws that were fair and equitable, and through the establishment of legal processes that were clear and transparent.

Jeremy Bentham, one of the classical school’s originators, epitomized the rational approach to crime and crime control. Bentham theorized that individuals were motivated by psychological hedonism; we all seek pleasure and avoid pain. Because of this, Bentham believed we were all capable of crime under the right circumstances. Our biologically driven urges were identical, and it was our social circumstances that dictate whether we decided to indulge in criminal actions.

From Bentham’s perspective—and consistent with the scientific paradigm introduced by Bayes’s theory of probability—an individual’s actions could be predicted through a mathematical formula that Bentham labeled felicity calculus. Through this formula, Bentham postulated that he could calculate the specific amount of pleasure an individual would derive from engaging in a particular crime. The formula, in turn, could be used by government to determine the extent to which it needed to restrict civil liberties, an action inherently painful to the individual and, therefore, undesirable except as absolutely necessary to protect the majority. Anticipating debates that remain unresolved, Bentham also opposed criminalizing behaviors that offended individual morality but that arguably did not cause pain. During his time, for example, he opposed the punishment of vestal virgins, who were buried alive when found to be unchaste. Bentham argued that their behavior produced no true evil and, therefore, should not be subject to punishment. Similarly, Bentham proposed that punishment should only be as severe as necessary to serve as a deterrent. For this reason, Bentham was an early opponent of capital punishment (see Box 1.1).

Box 1.1 Bentham’s Panopticon

Classical school criminologist Jeremy Bentham was a pioneer of efforts to rehabilitate criminals so they could successfully reenter society. Although considered then and now a bit bizarre, Bentham’s panopticon is one of the earliest attempts to emphasis rehabilitation over retribution. His round structure featured prison cells with glass windows that were clearly visible to a guard, who was stationed in an enclosed center. The guard was not only responsible for watching the prisoners but also for serving as an employer, engaging inmates in paid manual labor from which the guard would receive a portion of the proceeds. Should a prisoner recidivate, the guard would be fined, thus supporting his investment in their rehabilitation. In Bentham’s vision, panopticons would be located at the center of cities, as their high visibility would serve as deterrents to others tempted to engage in crime.

Bentham’s panopticon idea was rejected in his native England, as well as in France and Ireland. However, two structures conforming to his design were attempted in the United States.

The Western State Penitentiary was opened in Pittsburgh in 1826 but deemed “wholly unsuited for anything but a fortress” and was ordered rebuilt in 1883.

A second attempt was made in Illinois between 1916 and 1924. As one inmate stated, “They figured they were smart building them that way” [with cells built in a circle and facing a center]. “They figured they could watch every inmate in the house with only one screw [warden] in the tower. What they didn’t figure is that the cons know all the time where the screw is, too.”

The building was abandoned and a more conventional structure replaced it.

Bentham’s panopticon concept was reinvigorated in 1975 by French philosopher Michel Foucault. In his Discipline and Punish, Foucault used the panopticon as a metaphor for the way in which disciplinary societies subjugate citizens: “He is seen, but he does not see; he is an object of information, never a subject in communication.” Consequently, the surveilled engages in self-policing for fear of punishment.

Bentham’s original concept and Foucault’s expanded metaphor have been adopted by some as warnings of the consequences of eroding privacy, ranging from the proliferation of cookies on Internet websites to the closed-circuit television monitoring of public spaces.

It will be interesting to see if advances in neurocriminology extend the application of the metaphor to this discipline as well.

Bentham’s contemporary and fellow classical school theorist, the Italian criminologist Cesare Beccaria, likewise proposed that governmental authority should be restricted, and only extend to protecting individuals against war from enemies outside a nation’s borders and the chaos that would otherwise reign within.

Beccaria was disturbed by the routine use of torture in Western Europe during his time, which served not only to punish but also as a means of determining innocence or guilt, compelling confessions, and identifying accomplices. In response, he wrote his famous work, On Crime and Punishments.

Beccaria argued that crime control would only be effective when individuals—who were by nature rational and capable of making rational choices—knew the punishment for particular criminal actions in advance. This, in turn, could only be accomplished by publishing laws and punishments, by rendering criminal proceedings public, and by ensuring that punishment was delivered shortly after a crime was committed.

The Classical Theorists offered a logical solution to crime and crime control that appealed to individual rationality, and was premised on one’s ability to refrain from crime.

During the 19th century, several scientific and pseudoscientific developments would suggest that criminals did not have the volitional control upon which Classical Theorists relied.

The 19th Century: Phrenology, the Positivists, and Lombroso

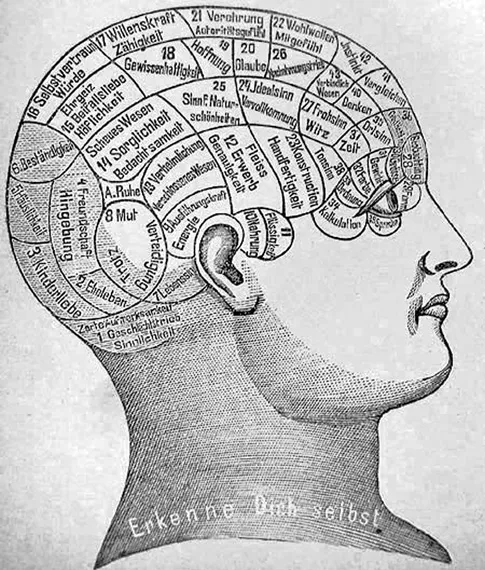

In early 19th-century Germany, physician Franz Joseph Gall advanced a theory that would later be called phrenology. Based upon his observations of the sizes of the heads of gifted classmates, evaluation of the bumps on the skulls of pick pockets, and postmortem examinations of more than 100 brains, Gall posited that intellect and personality could be linked to configurations of the skull. He asserted that mental functions were localized in specific regions of the brain and could be measured by feeling the bumps, indentations, and overall shape of the individual’s head. He mapped brain regions to brain functions, which he called faculties, including a faculty called “Combativeness” and one called “Acquisitiveness” (see Box 1.2).

His scientific basis for behavior was reinforced when naturalist and geologist Charles Darwin published On The Origin of Species, and later, The Descent of Man: and Selection in Relation to Sex. Darwin’s theory of evolution, which challenged the notion that man originated from a single act of God, widened the science–religion divide that had emerged in the prior century. It also supported the perspective that human action is biologically driven.

Box 1.2 Phrenology: Early Explorations of Brain Regions and Associated Functionality

Franz Gall’s system of phrenology became an international sensation following its ban by last Holy Roman Emperor of the German Nation, Franz II, who feared that its materialistic emphasis violated moral and religious principles.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Scan by de: Benutzer: Summi

Edited by “Wolfgang” [Public domain]

As reported by George Combe—lawyer and founder of the Edinburgh Phrenological Society—in 1835, Gall initially proposed 27 faculties associated with specific areas of the brain. These included the following:

Amativeness

Philoprogenitiveness

Adhesiveness

Combativeness

Destructiveness

Secretiveness

Acquisitiveness

Self-Esteem

Love of Approbation

Cautiousness

Eventuality and Individuality

Locality

Form

Language

Language (included also in organ 14)

Coloring

Tune

Number

Constructiveness

Comparison

Causality

Wit

Ideality

Benevolence

Imitation

Veneration

Firmness

From the context of these and other developments, the Positivist School of Criminology was born. Positivists asserted that crime should be studied scientifically and that criminal actions cannot be limited to legal definitions, which are subject to the whims of societal sensibilities. The positivists also believed that the proclivity to engage in criminal activity was, to a large extent, predetermined. Consequently, because criminals had somewhat limited volitional control of their actions, the positivists advocated for the treatment of criminals, rather than punishment.

One of the most prominent names in the positivist school was Cesare Lombroso, who has been referred to as “the Father of Criminology.”

Lombroso shifted the focus of criminology from criminal behavior—which had been a prominent focal point for his predece...