eBook - ePub

Bioengineering and Biophysical Aspects of Electromagnetic Fields, Fourth Edition

- 524 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bioengineering and Biophysical Aspects of Electromagnetic Fields, Fourth Edition

About this book

The two volumes of this new edition of the Handbook cover the basic biological, medical, physical, and electrical engineering principles. They also include experimental results concerning how electric and magnetic fields affect biological systems—both as potential hazards to health and potential tools for medical treatment and scientific research. They also include material on the relationship between the science and the regulatory processes concerning human exposure to the fields. Like its predecessors, this edition is intended to be useful as a reference book but also for introducing the reader to bioelectromagnetics or some of its aspects.

FEATURES

- New topics include coverage of electromagnetic effects in the terahertz region, effects on plants, and explicitly applying feedback concepts to the analysis of biological electromagnetic effects

- Expanded coverage of electromagnetic brain stimulation, characterization and modeling of epithelial wounds, and recent lab experiments on at all frequencies

- Section on background for setting standards and precautionary principle

- Discussion of recent epidemiological, laboratory, and theoretical results; including: WHO IARC syntheses of epidemiological results on both high and low frequency fields, IITRI lab study of cancer in mice exposed to cell phone-like radiation, and other RF studies

- All chapters updated by internationally acknowledged experts in the field

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Bioengineering and Biophysical Aspects of Electromagnetic Fields, Fourth Edition by Ben Greenebaum, Frank Barnes, Ben Greenebaum,Frank Barnes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Biotechnology in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Environmental and Occupational DC and Low Frequency Electromagnetic Fields

Ben Greenebaum

University of Wisconsin-Parkside

Kjell Hansson Mild

Umeå University

CONTENTS

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Naturally Occurring Fields

1.3 Artificial DC and Power Frequency EM Fields in the Environment

1.3.1 DC Fields

1.3.2 High-Voltage AC Power Lines

1.3.3 Exposure in Homes

1.3.4 Electrical Appliances

1.3.5 ELF Fields in Transportation

1.3.6 ELF Fields in Occupational Settings

1.3.7 Internal ELF Fields Induced by External and Endogenous Fields

1.4 Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

1.1 Introduction

We encounter electromagnetic (EM) fields, both naturally occurring and man-made, every day. This leads to exposure in our homes as well as outdoors and in our various workplaces, and the intensity of the fields varies substantially with the situation. Quite high exposure can occur in some of our occupations as well as during some personal activities, for instance, in trains, where the extremely low-frequency (ELF) magnetic field can reach rather high levels. The frequency of the fields we are exposed to covers a wide range, from static or slowly changing fields to the gigahertz range. However, measurements of the magnetic field at a particular location or near a particular piece of equipment can often be much higher than an individual’s average exposure across a day as measured by a personal monitor, since one moves from one place to another throughout the day, both in occupational and everyday settings (Bowman, 2014).

In this chapter, we give an overview of the fields we encounter in the steady direct current (DC) and low-frequency range (ELF, strictly speaking 30–300 Hz but taken here, as is usual in the bioelectromagnetics literature to extend from 0 to 3000 Hz) and in various situations. Higher frequency fields encountered are reviewed in Chapter 2 of BBA. Recent published reviews of common field exposures include Bowman (2014) on both ordinary environmental and occupational exposures and Gajšek et al. (2016), which discusses European exposures. The World Health Organization Environmental Health Criteria on static (WHO, 2006) and ELF fields (WHO, 2007) provide chapters on commonly encountered fields.

1.2 Naturally Occurring Fields

The most obvious naturally occurring field is the Earth’s magnetic field, known since ancient times. The total field intensity diminishes from the poles, as high as 67 μT at the south magnetic pole to as low as about 30 μT near the equator. In South Brazil, an area with flux densities as low as about 24 μT can be found. In addition, the angle of the Earth’s field to the horizontal (inclination) varies, primarily with latitude, ranging from very small near the equator to almost vertical at high latitudes. More information is available in textbooks (see, e.g., Dubrov, 1978) and in databases available on the Web (see, e.g., the U.S. National Geophysical Data Center, 2017).

However, the geomagnetic field is not constant, but is continuously subject to more or less strong fluctuations. There are diurnal variations, which may be more pronounced during the day and in summer than at night and in winter (see, e.g., Konig et al., 1981). There are also short-term variations associated with ionospheric processes. When the solar wind brings protons and electrons toward the Earth, phenomena like the Northern Lights and rapid fluctuations in the geomagnetic field intensity occur. The variation can be rather large; the magnitude of the changes can sometimes be up to 1 μT on a timescale of several minutes. The variation can also be very different in two fairly widely separated places because of the atmospheric conditions. There is also a naturally occurring DC electric field at the surface of the Earth in the order of 100–300 V/m (Earth’s surface negative) in calm weather; it can be 100 kV/m in thunderstorms, caused by atmospheric ions (NRC, 1986).

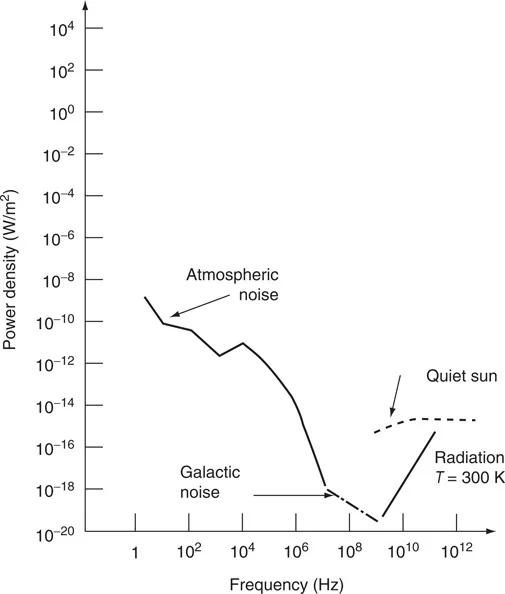

EM processes associated with lightning discharges are termed as atmospherics or “sferics” for short. They consist mostly of waves in the ELF and very low-frequency (VLF) ranges (3–30 kHz) (see Konig et al., 1981). Each second about 100 lightning discharges occur globally; and in the United States, one cloud-to-ground flash occurs about every second, averaged over the year Konig et al. (1981). The ELF and VLF signals travel efficiently in the waveguide formed by the Earth and the ionosphere and can be detected many thousands of kilometers from the initiating stroke. Since 1994, several experiments studying the effects of short-term exposure to simulated 10-kHz sferics have been performed at the Department of Clinical and Physiological Psychology at the University of Giessen, Germany (Schienle et al., 1996, 1999). In the ELF range, very low-intensity signals, called Schumann resonances, also occur. These are caused by the ionosphere and the Earth’s surface acting as a resonant cavity, excited by lightning (Konig et al., 1981; Campbell, 1999). These cover the low-frequency spectrum, with broad peaks of diminishing amplitude at 7.8, 14, 20, and 26 Hz and higher frequencies. Higher-frequency fields, extending into the microwave region, are also present in atmospheric or intergalactic sources. These fields are much weaker, usually by many orders of magnitude than those caused by human activity (compare Figure 1.1 and subsequent tables and figures in this chapter).

FIGURE 1.1

Power density from natural sources as a function of frequency. (Data from Smith, E. Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility. Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Piscataway, NJ, 1982. Graph adapted from Barnes, F.S. Health Phys. 56, 759–766, 1989. With permission.)

Power density from natural sources as a function of frequency. (Data from Smith, E. Proceedings of the IEEE Symposium on Electromagnetic Compatibility. Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Piscataway, NJ, 1982. Graph adapted from Barnes, F.S. Health Phys. 56, 759–766, 1989. With permission.)

1.3 Artificial DC and Power Frequency EM Fields in the Environment

1.3.1 DC Fields

Although alternate current (AC) power transmission is facilitated by the availability of transformers to change voltages, DC is also useful, especially since high-power, high efficiency solid-state electronic devices have become available. Overland high-voltage DC lines running at up to 1100 kV (circuits at ±550 kV) are found in Europe, North America, and Asia (Hingorani, 1996). Electric and magnetic field intensities near these lines are essentially the same as those for AC lines running at the same voltages and currents, which are discussed below. Because potentials on the cables do not vary in time and there are only two DC conductors (+ and −) instead of the three AC phases, the DC electric fields and space charge clouds of air ions that partially screen them are somewhat different from those near AC transmission lines, though the general features are the same, especially for positions away from the lines. Electric fields, corona, and air ions are discussed further in the AC transmission line section below (Kaune et al., 1983; Fews et al., 2002). For transfer of electric power between countries separated by sea, DC undersea power cables are especially useful, since their higher capacity causes decreased losses than with AC.

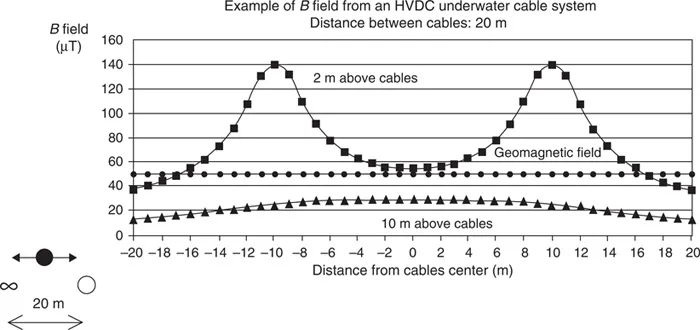

FIGURE 1.2

Predicted DC magnetic field from a high-voltage DC cable with the return cable placed at a distance of 20 m. The current in the cable was assumed to be 1333 A, which is the maximum design current. (From Hansson Mild, K. In Matthes, R., Bernhardt, J.H., and Repacholi, M.H., Eds. Proceedings from a joint seminar, International Seminar on Effects of Electromagnetic Fields on the Living Environment, of ICNIRP, WHO, and BfS, Ismaning, Germany, October 4–5, 1999, pp. 21–37. With permission.)

Predicted DC magnetic field from a high-voltage DC cable with the return cable placed at a distance of 20 m. The current in the cable was assumed to be 1333 A, which is the maximum design current. (From Hansson Mild, K. In Matthes, R., Bernhardt, J.H., and Repacholi, M.H., Eds. Proceedings from a joint seminar, International Seminar on Effects of Electromagnetic Fields on the Living Environment, of ICNIRP, WHO, and BfS, Ismaning, Germany, October 4–5, 1999, pp. 21–37. With permission.)

Examples are cables between Sweden and Finland, Denmark, Germany, and Gotland, a Swedish island in the Baltic Sea. A 254 km 450 kV 600 MW cable began operation in 2000 from Sweden to Poland (SwePol). In these cables DC is used, and the ELF component of the current is less than a few tenths of a percent. The maximum current in these cables is slightly above 1000 A, and the estimated normal load is about 30% or 400 A. Depending on the location of the return path, the DC magnetic field will range from a maximum disturbance of the geomagnetic field (with a return through water) to a minimal disturbance (with a return through a second cable as close as possible to the feed cable). With a closest distance of 20 m between the cables, the predicted field distribution can be seen in Figure 1.2, immediately above the cables (2 m), practically the same value as that obtained for a single wire. When the distance between cables is increased beyond 20 m, the distortion at a given distance rises above that of Figure 1.2. Since the cables are shielded, no electric field will be generated outside the cable. For a more detailed discussion of the fields associated with this technique, the reader is referred to the paper by Koops (1999).

Few other DC fields from human activity are broadly present in the environment, though very short-range DC fields are found near permanent magnets, usually ranging from a few tenths of a millitesla to a few millitesla at the surface of the magnet and decreasing very rapidly as one moves away. Occupationally encountered DC fields are discussed below.

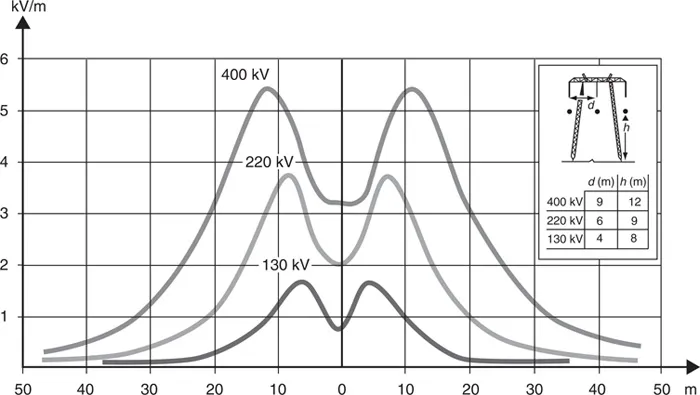

1.3.2 High-Voltage AC Power Lines

The electric and magnetic fields from high-voltage power lines have been figuring for a long time in the debate on the biological effects of EM fields. Although the AC power systems in the Americas, Japan, the island of Taiwan, Korea, and a few other places are 60 Hz, while most of the rest of the world is 50 Hz, the frequency difference has no effect on high-voltage transmission line fields. In the early days of bioelectromagnetics research, the electric field was considered the most important part, and measurements of field strengths were performed in many places. Figure 1.3 shows an example of such measurements from three different types of lines: 400, 220, and 130 kV lines, respectively. The field strength depends not only on the voltage of the line but also on the distance between the phases and the height of the tower. The strongest field can be found where the lines are closest to the ground, and this usually occurs midway between two towers. Here, field strengths up to a few kilovolts per meter can be found. Since the guidelines of the International Commission on Non-Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP, 1998) limit public exposure to 5 kV/m and there is no time averaging for low-frequency fields, people walking under high-voltage power lines may on some occasions be exposed in excess of existing international guidelines.

FIGURE 1.3

Electric field from three different high-voltage power lines as a function of the distance from the center of the line. In the inset the distance between the phases as well as the height above ground of the lines are given. (From Hansson Mild, K. In Matthes, R., Bernhardt, J.H., and Repacholi, M.H., Eds. Proceedings from a joint seminar, International Seminar on Effects of Electromagnetic Fields on the Living Environment, of ICNIRP, WHO, and BfS, Ismaning, Germany, October 4–5, 1999, pp. 21–37. With permission.)

Electric field from three different high-voltage power lines as a function of the distance from the center of the line. In the inset the distance between the phases as well as the height above ground of the lines are given. (From Hansson Mild, K. In Matthes, R., Bernhardt, J.H., and Repacholi, M.H., Eds. Proceedings from a joint seminar, International Seminar on Effects of Electromagnetic Fields on the Living Environment, of ICNIRP, WHO, and BfS, Ismaning, Germany, October 4–5, 1999, pp. 21–37. With permission.)

Because electric fields are well shielded by trees, buildings, or other objects, research in the 1970s and 1980s did not turn up any major health effects (see, e.g., Portier and Wolfe, 1998) and because of the epidemiological study by Wertheimer and Leeper (1979) (see also Chapter 13 in BMA), attention turned from electric to magnetic fields in the environment. The magnetic field from a transmission line or any other wire depends on the current load carried by the line, as well as the distance from the conductors; in Figure 1.4, calculations of the magnetic flux density from several different types of transmission lines are shown. There is a very good agreement between the theoretical calculation and the measured flux density in most situations. The flux density from two-wire power lines is directly proportional to the electric current, generally inversely proportional to the square of the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Editors

- List of Contributors

- 0. Introduction to Electromagnetic Fields

- 1. Environmental and Occupational DC and Low Frequency Electromagnetic Fields

- 2. Intermediate and Radiofrequency Sources and Exposures in Everyday Environments

- 3. Endogenous Bioelectric Phenomena and Interfaces for Exogenous Effects

- 4. Electric and Magnetic Properties of Biological Materials

- 5. Interaction of Static and Extremely Low-Frequency Electric Fields with Biological Materials and Systems

- 6. Magnetic Field Interactions with Biological Materials

- 7. Mechanisms of Action in Bioelectromagnetics

- 8. Signals, Noise, and Thresholds

- 9. Computational Methods for Predicting Electromagnetic Fields and Temperature Increase in Biological Bodies

- 10. Experimental Dosimetry

- 11. Overcoming the Irreproducibility Barrier: Considerations to Improve the Quality of Experimental Practice When Investigating the Effects of Low-Level Electric and Magnetic Fields on In Vitro Biological Systems

- 12. Radio Frequency Exposure Standards

- Index