![]()

Part I

Backdrop to Heritage Meanings

![]()

1

Prelude to the Unexpected

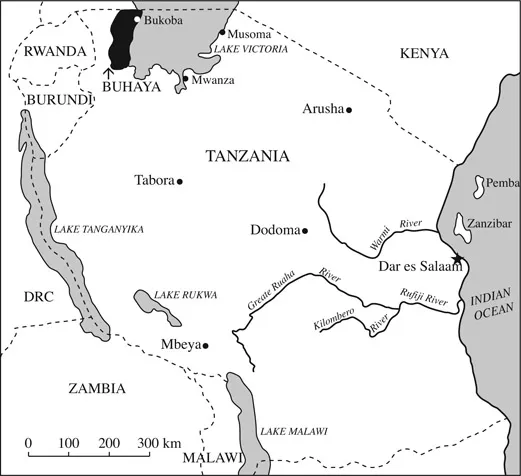

This book originates in serendipity. I returned to my original research region in northwestern Tanzania in 2008 after an absence of 24 years. I spent the first 15 years of my career researching indigenous histories and archaeology in the region,1 and I was looking for new research horizons elsewhere in Africa after a lengthy engagement in Eritrea (1996–2005). My return to Buhaya, along the littoral and immediate hinterland of the western Lake Victoria shore (Fig. 1.1), was to visit old friends and acquaintances. I found few old friends and former collaborators still living.2 It was an emotionally upsetting visit.

Though reports of the ravages of Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) had saturated the Western news media, there was no way that they prepared me or my wife, Jane, for the distressed social and economic conditions that we encountered. What followed was a deeply personal response to individual and community crises and desires expressed by those wanting to reclaim eroded identities once linked intimately to their heritage. Once engaged, I came to see this unique effort at heritage research and revitalization as a rare initiative of participatory community research and preservation.

Notes on an Ethnographic Approach to Heritage in Buhaya

The ethnographic observations on which this book is based are naturally selective and reflect my personal, academic, and philosophical interests. I am aware that my motives for representations are polyvalent and may be attuned to particular intellectual paradigms, making observations seem in tune with various values—global and local, and appearing to be empathetic to the local scene. Often in such treatments, critical observations that capture negative, arrogant, and rude personalities are purged to provide an agreeable rendering. I was repeatedly faced with such circumstances—how would I write about events that were distasteful to me and sometimes to local participants? To whitewash such events does a disservice to the record and misconstrues the context within which important actions take place.

Fig. 1.1 Map of Tanzania with Buhaya, in black.

My sense of how to reach a balance is to give my honest appraisal of what I witnessed and not avoid uncomfortable language or interactions. By working closely with local collaborators, it is inevitable that personality quirks will surface, including my own. Sometimes such traits will seriously influence the direction that events unfold and the way decisions are made. Close collaborators may invite full disclosure of their roles, but they may also be justifiably offended and angry over negative portrayals. There is no right path to take in such circumstances; the only option is to protect identities when harm may come to the person(s) and families involved, but to report openly and disclose all dimensions of the detail known to the observer in a summary representation that does not test the patience of the reader.

I also try to reach a balance in my depictions of the Katuruka heritage experiment and the other heritage initiatives that followed by ethical assessments of various settings, trying to see the relative merits of full disclosure (within my very limited perspective) mixed with constantly shifting needs for confidentiality. Because the Katuruka committee and its collaborators were partly engaged in a documentary project, they and most participants wanted their names attached to testimonies. However well motivated these sentiments were, there are instances in which names attached to testimonies do not serve a positive purpose and in fact may lead to misunderstandings in the community. In such cases I have used coded references or pseudonyms. In other cases such treatments, once vetted by local participants, have been restored. In the case of my involvement with heritage issues surrounding both Katuruka and Kanazi Palace, sensitive issues of confidentiality arise with participants. Because of controversial positions some participants adopted and their standing in the broader Haya community, I refer to them as “clan elders” or “female elder,” etc., generics that capture their roles but avoid stigmatizing them as persons.

It is important that the key actors in the Katuruka heritage initiative be given full credit for their visionary and risky initiative. They expect and deserve acknowledgement for their contributions. At the same time, there were times when key characters tried to influence the welfare of the project or even to use the initiative to accrue influence, power, and other advantages. These are natural though disappointing occurrences under conditions of limited good. If the rendering of sensitive internal affairs may threaten the standing or reputation of any person, then I also use their generic role in the community or use a generalized reference, such as “a leader of the census.”

If I as a participant learned anything from the Katuruka experiment, it’s that “all politics are local” is a maxim of great strength and pertinence. Political positioning and manipulations were a constant part of the dynamic, right from the first committee meeting on Thursday, July 24, 2008. Politics are an important a part of the story, and in the case of public political figures assigning pseudonyms is meaningless. For example, it is pointless to conceal that the village chairman was viewed by some of the village residents in an uncomplimentary manner. When he attended the first committee meeting, he boldly informed the meeting that as village chairman he should serve on the steering committee that was being formed at the meeting. His participation was rejected.

I reacted in a manner that was in tune with how politics were organized during the 1970s and 1980s when I conducted village-based research in Kagera Region. Then village chairmen and village secretaries (the party representative) along with cell leaders absolutely ruled decision making in the communities. No one would have dared challenge their authority. I was worried that a rebuffed village chairman might cause problems for the committee.3 My notes from that part of the meeting say:

I step in to modulate this disagreement, suggesting that his participation could be temporary, but this elicits more fervent opposition to the idea. Some do not care for his officious attitude; for a while it seems like his power concerns will risk the project. But the committee chair wins the day and moves on with the committee to draft a list of priorities.

I highlight this issue because in many ways it typifies some of the interactions that arose during this heritage initiative. Acting as the chairman of the Katuruka heritage initiative, Benjamin Shegesha’s strong personality (which rubbed some people the wrong way) and certainty came from his being a former cultural officer, in fact the very first cultural officer in Tanzania by his reckoning. Confidence bred from that experience as well as a naturally commanding attitude was his hallmark. His passing in September of 2012 left an enormous void. His loss cannot be measured. He carried forward the vision around which others mobilized, though he was at times a difficult leader. Despite his foibles, people continue to recognize him for the visionary he was.

A Personal Perspective

What I write here is a personal narrative, accompanied by a keen awareness that my observations relate to a range of experiences found in the practice of collaborative archaeology and heritage elsewhere, particularly in North America and Australia. Community engagements go by a variety of rubrics including public archaeology, indigenous archaeology, participatory community research, community-based archaeology, and a host of other related practices (see Smith and Waterton 2012 for a full list of permutations). What I discuss here is best called community-based participatory research and development that incorporates a healthy dose of heritage preservation and revitalization of indigenous management principles. It is collaborative in its involvement of different stakeholders working together towards common goals. And it is participatory in the sense that local participants worked alongside foreign counterparts after villagers initiated research into heritage and archaeology. Its developmental thrust included development of the capacity to interpret and present local heritage tours to visitors and students as well as a heritage infrastructure that would lead to employment of village youth. Finally, its concern with preservation simultaneously incorporated the revitalization of important heritage sites and their associated meanings on local landscapes and in local knowledge archives, values once deeply embedded in Haya culture.

Where and What is Community?

It is reasonable to question what I mean by community in the narratives that unfold in the chapters that follow. This question has been at the forefront of community studies in heritage and archaeology for some time (e.g., Hughes 2008; Leeuw et al. 2012; McClanahan 2007; Stoecker 2009). If no one in a village, urban neighborhood, region, or a professional or voluntary society identifies with heritage values or a heritage property (Mydland and Grahn 2012), then “community” may be ephemeral, as Chirikure and colleagues (Chirikure et al. 2010; Chirikure and Pwiti 2008) point out at the Khami World Heritage Site in Zimbabwe, where there is an absence of people who identify with this site given the relocation of people for land alienation during colonial times. To unlock understanding of where community is situated and how it is defined requires ethno-graphic observation of the source of community initiatives and participation. In the case of Katuruka village and neighboring Nkimbo village, community is found within rural residential settings in which kinship relations, though significantly weakened, still constitute a point of identity. The Katuruka initiative, however, transcended kin relations to encompass those who identified with the project goals. Many people directly participated in the research phase, offering their knowledge to the organizing committee. Some residents performed heritage work such as reconstructing shrines. Yet others participated in assisting with gathering construction materials, road building, and representing the project to a broader public. Some people while not directly engaging in project activities nonetheless offered their encouragement and followed the project with interest. Participants constituted of a majority of residents over the age of 25. Of these, some have lived and worked outside the village for extended periods of their lives, showing its dynamic qualities and lack of boundaries over time.

Community in the case of the Kanazi Palace project was more limited and fraught with divisions. As I note in Chapter 17, the initial community was limited to several members of the royal family and the royal clan. These two groups were burdened by negative characterizations arising out of popular responses to the ruling family during the 20th century. Though working with the royal family was key to unlocking important insights into the heritage of the palace complex, it also carried a divisive factor—the estrangement of the royal family from the royal clan. Reaching into surrounding and distant villages to seek participants for the oral tradition component of the project was critical for gaining access to wider heritage knowledge. Diversity of community makeup resulted when engaging non-royal oral commentators and by working closely with non-royal craftsmen who expanded the scale and the level of active participation. With this expanded participation by the inclusion of different socioeconomic groups, a diverse community of interest was spread over a large physical landscape.

The studies in this book challenge Hughes’s (2008) claim that community archaeology and heritage studies foster a sense of parochialism, possessiveness, and activist agendas; these are characterizations that belie a lack of familiarity with processes of local engagement. Research results when arising out of community-based participation may have significant global implications (see Chapter 13)—certainly local in genesis but hardly parochial in outcome. The idea that community engagement ipso facto means an activist agenda is a naive appraisal that overlooks deep commitments to enhance well-being and social justice as integral to community goals to recuperate threatened heritage and to preserve knowledge into the future (see Baird 2014; Little 2009).

A Biography of Community Engagements

What makes these multifaceted endeavors distinctive is that they were initiated and launched by rural people in northwestern Tanzania, not by a government agency, international aid agency, or academic researcher. In Katuruka, a few inspired individuals gathered together to follow a collective agenda that speaks to deeply felt cultural needs and concerns. Acting on desires to recuperate heritage values was highly personal and emotional, investments with potent affect in this village-based initiative and its related spin-off projects. This requires departing from a typical academic treatment to adopt a form of representation more in keeping with the setting—a biographical narrative. In this portrait of community-based participatory research and heritage revitalization, I share my observations—strictly my own and perhaps quite different from other participants—as a series of insights into the human side of community approaches and as a means to address the critique that community archaeology and heritage practices often avoid discussion of problems and failures by stressing only positive results. Both inform the narrative that follows.

I also tack between my experiences as a transitory member of several communities seeking new directions for their futures and the formal literature discussing these topics in archaeology and heritage studies (Chapters 7 and 10). This is purposeful. It is important to place local experiences and experiments into a broader context as evidenced in the literature, but it is also critical that the inside story be presented in as honest and forthright manner as possible, compelling a narrative partially wrapped in an autoethnographic approach (e.g., Ellis and Bochner 2000, 2006; Schmidt 2010). The contrast between the two often highlights the removed and distanced quality manifest in some discourses about heritage, particularly about human rights and heritage. An autoethnographic approach helps to temper some of these pitfalls by shifting focus and responsibility for the narrative to the observer, though it also runs the risk of appearing to be self-serving and ethnographer-centric. I try to manage such risks by a reflexive approach that hopefully tempers the bias of my point of view.

Through time, I found my role changing from a participant in a local research and development initiative to one in which I played a partial, secondary management role by assisting the village committee with modest fundraising (project manager). As I have moved through this experience over the last seven years, I am keenly aware that I am also a co-producer of local knowledge. Though this was not an original motive for my participation, as various events and knowledge have emerged I have come to realize that I cannot ignore my responsibilities as an anthropologist and historian to share useful insights and knowledge with a broader public. There are new lessons to learn from a biography of community engagement with archaeology and heritage work. This book is an attempt at sharing these insights in a manner that is both personalized narrative and analytical examination, hopefully providing different angles of view for heritage studies.

Notes