- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Power Quality

About this book

Frequency disturbances, transients, grounding, interference…the issues related to power quality are many, and solutions to power quality problems can be complex. However, by combining theory and practice to develop a qualitative analysis of power quality, the issues become relatively straightforward, and one can begin to find solutions to power quality problems confronted in the real world.

Power Quality builds the foundation designers, engineers, and technicians need to survive in the current power system environment. It treats power system theory and power quality principles as interdependent entities, and balances these with a wealth of practical examples and data drawn from the author's 30 years of experience in the design, testing, and trouble-shooting of power systems. It compares different power quality measurement instruments and details ways to correctly interpret power quality data. It also presents alternative solutions to power quality problems and compares them for feasibility and economic viability.

Power quality problems can have serious consequences, from loss of productivity to loss of life, but they can be easily prevented. You simply need a good understanding of electrical power quality and its impact on the performance of power systems. By changing the domain of power quality from one of theory to one of practice, this book imparts that understanding and will develop your ability to effectively measure, test, and resolve power quality problems.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction to Power Quality

1.1 DEFINITION OF POWER QUALITY

Power quality is a term that means different things to different people. Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers (IEEE) Standard IEEE1100 defines power quality as “the concept of powering and grounding sensitive electronic equipment in a manner suitable for the equipment.” As appropriate as this description might seem, the limitation of power quality to “sensitive electronic equipment” might be subject to disagreement. Electrical equipment susceptible to power quality or more appropriately to lack of power quality would fall within a seemingly boundless domain. All electrical devices are prone to failure or malfunction when exposed to one or more power quality problems. The electrical device might be an electric motor, a transformer, a generator, a computer, a printer, communication equipment, or a household appliance. All of these devices and others react adversely to power quality issues, depending on the severity of problems.

A simpler and perhaps more concise definition might state: “Power quality is a set of electrical boundaries that allows a piece of equipment to function in its intended manner without significant loss of performance or life expectancy.” This definition embraces two things that we demand from an electrical device: performance and life expectancy. Any power-related problem that compromises either attribute is a power quality concern. In light of this definition of power quality, this chapter provides an introduction to the more common power quality terms. Along with definitions of the terms, explanations are included in parentheses where necessary. This chapter also attempts to explain how power quality factors interact in an electrical system.

1.2 POWER QUALITY PROGRESSION

Why is power quality a concern, and when did the concern begin? Since the discovery of electricity 400 years ago, the generation, distribution, and use of electricity have steadily evolved. New and innovative means to generate and use electricity fueled the industrial revolution, and since then scientists, engineers, and hobbyists have contributed to its continuing evolution. In the beginning, electrical machines and devices were crude at best but nonetheless very utilitarian. They consumed large amounts of electricity and performed quite well. The machines were conservatively designed with cost concerns only secondary to performance considerations. They were probably susceptible to whatever power quality anomalies existed at the time, but the effects were not readily discernible, due partly to the robustness of the machines and partly to the lack of effective ways to measure power quality parameters. However, in the last 50 years or so, the industrial age led to the need for products to be economically competitive, which meant that electrical machines were becoming smaller and more efficient and were designed without performance margins. At the same time, other factors were coming into play. Increased demands for electricity created extensive power generation and distribution grids. Industries demanded larger and larger shares of the generated power, which, along with the growing use of electricity in the residential sector, stretched electricity generation to the limit. Today, electrical utilities are no longer independently operated entities; they are part of a large network of utilities tied together in a complex grid. The combination of these factors has created electrical systems requiring power quality.

The difficulty in quantifying power quality concerns is explained by the nature of the interaction between power quality and susceptible equipment. What is “good” power for one piece of equipment could be “bad” power for another one. Two identical devices or pieces of equipment might react differently to the same power quality parameters due to differences in their manufacturing or component tolerance. Electrical devices are becoming smaller and more sensitive to power quality aberrations due to the proliferation of electronics. For example, an electronic controller about the size of a shoebox can efficiently control the performance of a 1000-hp motor; while the motor might be somewhat immune to power quality problems, the controller is not. The net effect is that we have a motor system that is very sensitive to power quality. Another factor that makes power quality issues difficult to grasp is that in some instances electrical equipment causes its own power quality problems. Such a problem might not be apparent at the manufacturing plant; however, once the equipment is installed in an unfriendly electrical environment the problem could surface and performance suffers. Given the nature of the electrical operating boundaries and the need for electrical equipment to perform satisfactorily in such an environment, it is increasingly necessary for engineers, technicians, and facility operators to become familiar with power quality issues. It is hoped that this book will help in this direction.

1.3 POWER QUALITY TERMINOLOGY

Webster’s New World Dictionary defines terminology as the “the terms used in a specific science, art, etc.” Understanding the terms used in any branch of science or humanities is basic to developing a sense of familiarity with the subject matter. The science of power quality is no exception. More commonly used power quality terms are defined and explained below:

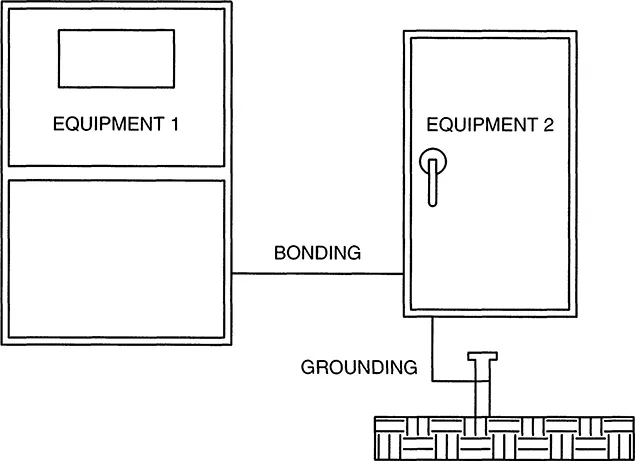

Bonding — Intentional electrical-interconnecting of conductive parts to ensure common electrical potential between the bonded parts. Bonding is done primarily for two reasons. Conductive parts, when bonded using low impedance connections, would tend to be at the same electrical potential, meaning that the voltage difference between the bonded parts would be minimal or negligible. Bonding also ensures that any fault current likely imposed on a metal part will be safely conducted to ground or other grid systems serving as ground.

Capacitance — Property of a circuit element characterized by an insulating medium contained between two conductive parts. The unit of capacitance is a farad (F), named for the English scientist Michael Faraday. Capacitance values are more commonly expressed in microfarad (μF), which is 10–6 of a farad. Capacitance is one means by which energy or electrical noise can couple from one electrical circuit to another. Capacitance between two conductive parts can be made infinitesimally small but may not be completely eliminated.

Coupling — Process by which energy or electrical noise in one circuit can be transferred to another circuit that may or may not be electrically connected to it.

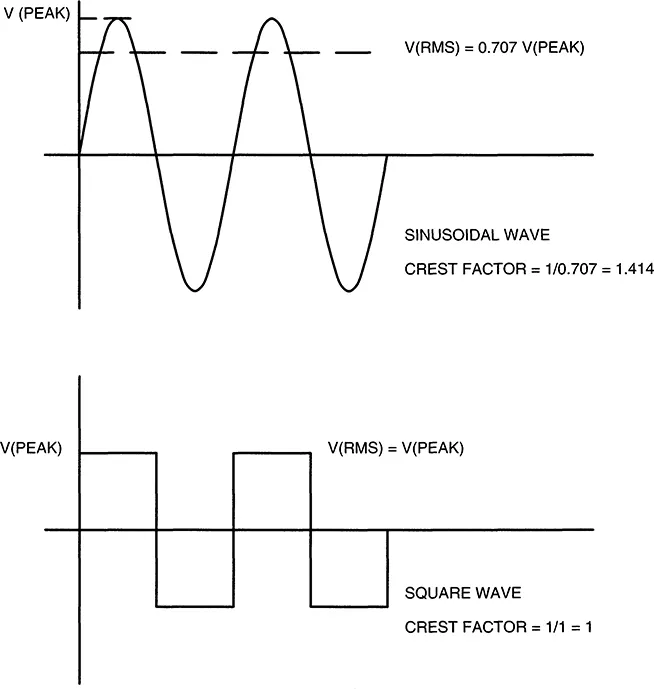

Crest factor — Ratio between the peak value and the root mean square (RMS) value of a periodic waveform. Figure 1.1 indicates the crest factor of two periodic waveforms. Crest factor is one indication of the distortion of a periodic waveform from its ideal characteristics.

FIGURE 1.1 Crest factor for sinusoidal and square waveforms.

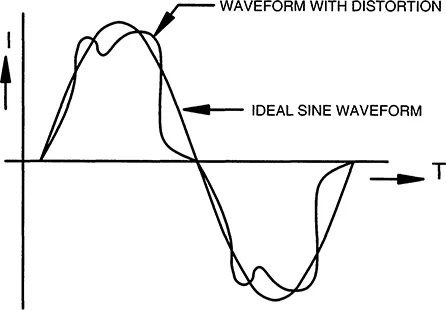

FIGURE 1.2 Waveform with distortion.

Distortion — Qualitative term indicating the deviation of a periodic wave from its ideal waveform characteristics. Figure 1.2 contains an ideal sinusoidal wave along with a distorted wave. The distortion introduced in a wave can create waveform deformity as well as phase shift.

Distortion factor — Ratio of the RMS of the harmonic content of a periodic wave to the RMS of the fundamental content of the wave, expressed as a percent. This is also known as the total harmonic distortion (THD); further explanation can be found in Chapter 4.

Flicker — Variation of input voltage sufficient in duration to allow visual observation of a change in electric light source intensity. Quantitatively, flicker may be expressed as the change in voltage over nominal expressed as a percent. For example, if the voltage at a 120-V circuit increases to 125 V and then drops to 117 V, the flicker, f, is calculated as f = 100 × (125 – 117)/120 = 6.66%.

Form factor — Ratio between the RMS value and the average value of a periodic waveform. Form factor is another indicator of the deviation of a periodic waveform from the ideal characteristics. For example, the average value of a pure sinusoidal wave averaged over a cycle is 0.637 times the peak value. The RMS value of the sinusoidal wave is 0.707 times the peak value. The form factor, FF, is calculated as FF = 0.707/0.637 = 1.11.

Frequency — Number of complete cycles of a periodic wave in a unit time, usually 1 sec. The frequency of electrical quantities such as voltage and current is expressed in hertz (Hz).

Ground electrode — Conductor or a body of conductors in intimate contact with earth for the purpose of providing a connection with the ground. Further explanation can be found in Chapter 5.

Ground grid — System of interconnected bare conductors arranged in a pattern over a specified area and buried below the surface of the earth.

Ground loop — Potentially detrimental loop formed when two or more points in an electrical system that are nominally at ground potential are connected by a conducting path such that either or both points are not at the same ground potential.

FIGURE 1.3 Bonding and grounding of equipment.

Ground ring — Ring encircling the building or structure in direct contact with the earth. This ring should be at a depth below the surface of the earth of not less than 2.5 ft and should consist of at least 20 ft of bare copper conductor not smaller than #2 AWG.

Grounding — Conducting connection by which an electrical circuit or equipment is connected to the earth or to some conducting body of...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- title

- copy

- dedication

- preface

- Preface

- 1 1 Introduction to Power Quality

- 2 Power Frequency Disturbance

- 3 Electrical Transients

- 4 Harmonics

- 5 Grounding and Bonding

- 6 Power Factor

- 7 Electromagnetic Interference

- 8 Static Electricity

- 9 Measuring and Solving Power Quality Problems

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Power Quality by C. Sankaran in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Energy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.