eBook - ePub

Conversational Intelligence

How Great Leaders Build Trust and Get Extraordinary Results

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conversational Intelligence

How Great Leaders Build Trust and Get Extraordinary Results

About this book

The key to success in life and business is to become a master at Conversational Intelligence. It's not about how smart you are, but how open you are to learn new and effective powerful conversational rituals that prime the brain for trust, partnership, and mutual success. Conversational Intelligence translates the wealth of new insights coming out of neuroscience from across the globe, and brings the science down to earth so people can understand and apply it in their everyday lives. Author Judith Glaser presents a framework for knowing what kind of conversations trigger the lower, more primitive brain; and what activates higher-level intelligences such as trust, integrity, empathy, and good judgment. Conversational Intelligence makes complex scientific material simple to understand and apply through a wealth of easy to use tools, examples, conversational rituals, and practices for all levels of an organization.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conversational Intelligence by Judith E. Glaser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Conversational Intelligence and Why We Need It

1

What We Can Learn from Our Worst Conversations!

I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.—PENTAGON SPOKESMAN ROBERT MCCLOSKEY DURING A PRESS BRIEFING ABOUT THE VIETNAM WAR

Conversations are multidimensional, not linear. What we think, what we say, what we mean, what others hear, and how we feel about it afterward are the key dimensions behind Conversational Intelligence. Though conversations are not simply “ask and tell” levels of discourse, we often treat them as though they are.

Good Intentions, Bad Impact

A decade ago, I had a coaching client who I knew from the outset was going to be challenging. As it turned out, we fired each other after six months. None of us likes to fail, let alone anticipate the prospect of failure. When my client—let’s call him Anthony—interacted with me, he came across as a tough, arrogant executive who lived inside his head and didn’t share his feelings. In retrospect, I know we were caught in our biases about each other and about what coaching involved. I was trapped in a dance of distrust with my client, but at the time, I didn’t know enough to understand that I, the coach, was being thrown off by the very set of skills I would acquire over the next fifteen years.

Coaching requires that you know yourself first; from that platform you can help others know themselves. If a coach—in this case, me—is not seasoned enough or aware enough to handle a difficult client like Anthony, she is not the right coach. But I didn’t know this yet, and I plowed forward in our conversations, believing I would figure out a way to penetrate his shell and connect with him.

Feel-Good and Feel-Bad Conversations

When we are having a good conversation, even if it’s a difficult one, we feel good. We feel connected to the other person in a deep way and we feel we can trust him. In good conversations, we know where we stand with others—we feel safe.

In our research over thirty years, trust is brought up as a key descriptor of a good conversation. People will say, “I feel open and trusting. I could say what was on my mind.” Or, “I don’t have to edit anything, and I can trust it won’t come back to hurt me.”

Conversations are the golden threads, albeit sometimes fragile ones, that keep us connected to others. And why is that important? Human beings have hardwired systems exquisitely designed to let us know where we stand with others; based on our quick read of a situation, our brains know whether we should operate in a protective mode or be open to sharing, discovery, and influence.

The neural network that allows us to connect with other human beings was discovered in 1926 by Constantin von Economo, who came across unusually shaped long neurons in two places—in the prefrontal cortex of the brain—the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and in the fronto-insular (FI) cortex. What von Economo discovered is that these neurons extend into the gut, literally the stomach, and inform our instinctive network by responding to socially relevant cues—be it a frowning face, a grimace of pain, or simply the voice of someone we love.1 This network of special neurons, now referred to as VENs, enables us to keep track of social cues and allows us to alter our behavior accordingly.2 This is one of our most powerful and profoundly active networks, yet it is one relatively rarely discussed in the neuroscience literature. My assumption is that it’s not discussed because researchers are still not sure how it impacts observable behavior, which is easier to study than instincts or intuition. Networks connected with the stomach—often referred to as “gut instinct”—are simply a difficult research subject. It is much harder to design a study and draw conclusions about internal workings than about behavior—and scientific research is designed to help us draw conclusions. When we are in conversation with others, perhaps even before we open our mouths, we size them up and determine whether we trust or distrust them; once this happens, our brains are ready to either open up or close down. Bad conversations trigger our distrust network and good conversations trigger our trust network. Each influences what we say, how we say it, and why we say it, and the networks even have a heavy hand in shaping the outcomes of each conversation.

Conversations Trigger Neurochemistry

At the moment we make contact with other people, biochemical reactions are triggered at every level of our bodies. Our heart responds in two ways—electrochemical and chemical. When we interact with others we have a biochemical or neurochemical response to the interaction, and we pick up electrical signals from others as well. As our bodies read a person’s energy—which we pick up within ten feet of the person—the process of connectivity begins. We experience others through electrical energy, feelings, which we have at the moment of contact; on top of this we layer our old memories about the person, ideas, beliefs, or stuff we make up, all while trying to make sense of who he is. Can we trust him? Will he hurt us? Can we connect and add value to each other’s lives?

Making Stuff Up

What made my conversations with my former client Anthony so bad? Many of us have grown up believing that conversations occur when two people give and receive information from each other. What we know today is that conversations are multidimensional and multi-temporal. That means that some parts of the brain process information more quickly than others, and our feelings emerge before we are able to put words to them. The things we say, the things we hear, the things we mean, and the way we feel after we say it may all be separate, emerging at different times; so you can see how conversations are not just about sharing information—they are part of a more complex conversational equation. When what we say, what we hear, and what we mean are not in agreement, we retreat into our heads and make up stories that help us reconcile the discrepancies.

My frustration with not being able to have an open and trusting conversation with Anthony led me to start making “movies” about him in my head while we conversed. I found myself being very critical of Anthony’s ways, his style of talking and his intentions. I found myself leaving empathy behind and putting judgment first. I imagined Anthony as an arrogant bully and continued to embellish my feelings about him until I cast him as the worst leader I had ever met. At times, I imagined that Anthony didn’t have any feelings, and was out to prove that he was right and I was wrong. The better my moviemaking abilities got, the less able I was to really connect with him and help him as a coach.

To be fair, Anthony had a huge challenge in front of him. He had been hired as the new president of a global publishing company poised to transform its offerings from print to digital. Some saw Anthony as the next CEO, conditional upon his successful completion of my six-month executive coaching process. We both had a lot riding on our engagement.

Failure to Connect

I’m not sure if it was my fear of failure or Anthony’s stubbornness and low level of awareness that took me off my game or—worse yet—a combination of both. I was convinced that he didn’t get how important connecting was, and I also told myself he didn’t really care. By the time I had cast our relationship in hopeless terms, I was unable to do what a good coach should do: facilitate a wake-up call for change. Instead, by slipping into my own moviemaking, I contributed to our failure to connect.

After making several attempts to put the subject of connectivity on the table with Anthony during our first few coaching sessions, I realized that he, too, was composing, directing, and starring in a “movie in his mind” about who he was, what he needed to do to be successful, and why I was wrong and he was right. I remember leaving one of the early sessions feeling insecure about my coaching abilities. At times, I even felt like the coaching roles had changed: he was driving and I was being taken along for the ride. In my mind, I had really messed up as Anthony’s coach. I failed to connect on the very important subject of connecting, and this missed opportunity could be life changing for him—and perhaps even life changing for me.

The Push and Pull of Conversations

Upon reflection, I realize my fear of failure made me push Anthony harder. We were both caught up in being right and neither of us knew it. When we are trapped in our need to be right, we want to win, we fight to win, and we go into overdrive trying to persuade others to our point of view.

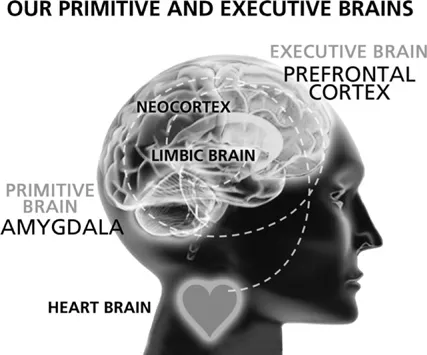

When we are out to win at all costs, we operate out of the part of the primitive brain called the amygdala. This part is hardwired with the well-developed instincts of fight, flight, freeze, or appease that have evolved over millions of years. When we feel threatened, the amygdala activates the immediate impulses that ensure we survive. Our brains lock down and we are no longer open to influence. (You’ll learn how to get unstuck and become more agile in part 2 of this book.)

FIGURE 1-1: Our Primitive and Executive Brains

On the other side of the brain spectrum is the prefrontal cortex. This is the newest brain, and it enables us to build societies, have good judgment, be strategic, handle difficult conversations, and build and sustain trust. Yet when the amygdala picks up a threat, our conversations are subject to the lockdown, and we get more “stuck” in our point of view!

“You’ve got to be nicer to people,” I found myself saying to Anthony, as though telling or yelling would make him think in new ways. I was falling into the traps I teach leaders not to fall into—I was triggered, I was biased, and I couldn’t recover in the moment. Recovery, one of the skills I so dutifully teach others to use—was out of my grasp at the moment I needed it most. (More about pattern interrupt, refocusing reframing, and redirecting in chapter 8, “Conversational Agility.”)

“Nice is not important,” Anthony said; now trying to convince me that his view of reality was more real than mine. “My job is getting the next strategy in place and I’ve got to focus on who on my team can be a producer, not who is nice. If I need to fire the top people on my staff, so be it. They’re from the old school. They don’t get the digital world and I don’t need them here.”

I was caught in the “Tell—Sell—Yell Syndrome”: tell them once, try to sell them on the reason you are right, then yell! When we are in this posture, we are seeking to gain power over others, and I didn’t realize the implications. Anthony was not listening. He didn’t appear like he cared to. He was right, and others were wrong.

He showed little respect for all the years of learning and experience his team brought to the table, and I saw him as someone with his mind made up. He was forceful and single-minded in his efforts at persuasion, telling me why cleaning house was clearly the right strategy for success. While all my good instincts told me to help him explore the best way of getting to know his new company and culture during his first one hundred days, I was finding that task outside my skill set.

It’s All in Your Head!

In different ways, I tried to initiate with Anthony the missing conversation about building trusting relationships and getting to know his team’s real talents before taking drastic action. But the words didn’t come out of my mouth in a way he could hear: I told him, “You must realize how important your feelings toward your people are in getting them to be good producers.” I tried being eloquent and provocative— even straightforward—but I was not getting through.

I tried again: “You haven’t even conversed openly with your team and found out what they can or cannot do. This is all in your head.” In retrospect, I realize that the more I pushed the less he listened. His mind was closed to new ways of looking at the situation—he was emotional toward me and emotional about his prospects for success. “Right now, nothing is as important as the bottom line,” Anthony said. “And that is what I’ve been cha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Introduction Discovering a New Intelligence

- Part I Conversational Intelligence and Why We Need It

- Part II Raising Your Conversational Intelligence

- Part III Getting to the Next Level of Greatness

- Epilogue Creating Conversations That Change the World

- Endnotes

- References

- Acknowledgments

- Index