- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

59 Checklists for Project and Programme Managers

About this book

This book is aimed at people who are involved in, or are about to become involved in, a project or programme. If you feel your project and programme management competences can be improved, 59 Checklists for Project and Programme Managers will undoubtedly offer you useful suggestions. The practical approach taken by Rudy Kor and Gert Wijnen makes this an easy book to dip into when you want to know what to do in a particular situation. The book covers a range of topics, including: choosing the right approach, organising for projects and programmes, team management, starting and executing projects, and programme management. For each topic, the book provides a series of checklists to lead you through the most important aspects of each subject. With such hands-on advice from acknowledged experts so easily available, this is a book which no project or programme manager should be without. The checklist approach provides readers with tools and techniques for this particular way of working and will enable new or experienced team members to plan, initiate, run and deliver whatever the output their organisations' programme or projects require.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

You Have to Choose the Right Approach

There is something odd in our approach to project and programme management compared to a more natural way of working. People confronted with a unique assignment have a natural tendency to act first and think later – especially when it’s an assignment that interests them. In addition, most people when they really want something tend to overlook all of the consequences, such as the real cost or exact specifications. In practice, this makes a professional approach to projects and programmes essential. Whether you are dealing with an extremely complicated technological assignment, such as building a tunnel, or a more cerebral one, such as a policy determination, the approach chosen must be carried forward in the proper way, not as an obligatory procedure or dogma, but as a means of helping people to work together.

At the start of an assignment, professional project and programme management is a lot less fun than jumping in feet first. Having to first think carefully exactly which problems have to be tackled, what your goals are, what the result must be and which paths to follow or, more importantly, not to follow, is an effective temper to your enthusiasm.

Project and programme management forces those involved to reach agreements on planning, tasks, authority and responsibilities before the assignment even gets off the ground – activities far more boring than simply launching yourself in at the deep end. But this initial investment always pays off in the end.

Within a short space of time it will become clear that when jumping in feet first, people’s enthusiasm soon wanes. Feelings of frustration soon emerge: ‘It’s clear everyone wants something different’, ‘No one’s exactly waiting for this’ and ‘No one knows what to do next’. The end result is usually a new set of frustrations: ‘What did I tell you, we can never do anything right’. On the other hand assignments become progressively more fun when project or programme management is used skilfully, occasionally because a quick decision is taken not to go ahead, but more commonly because the results or the goals become clearer and appear to be within reach.

Regardless of whether an assignment is the result of a policy change, the introduction of a new product, launch into a new market or outsourcing services, in all cases it will involve drastic changes that require an appropriate management method. The choice of a method is often subconscious and may sometimes even be dictated by fashion. There is a great deal of confusion when it comes to talking about the management of projects, programmes and processes; one person’s programme is another’s process. This confusion can lead to an approach that’s completely wrong for the assignment, with the result that goals and/or results fail to be reached, are reached too late or inefficiently; people continually pull out of the project or the costs become astronomical. To help avoid these unnecessary frustrations you need to decide consciously which of these methods to use.

Projects (result or deliverable oriented), programmes (goal or outcome oriented) and processes (action or interaction oriented) do not exist as such. You won’t find projects, programmes or processes just lying around – they are not tangible. A collection of activities designed to create a unique product, strive for unique goals or initiate actions can be turned into projects, programmes and processes respectively. It is a conscious choice to call a volume of work a project, a programme or a process and to use the appropriate management method associated with each. This is the only way a manager in the role of owner or in the role of project, programme or process manager can do their job properly.

In this book we concentrate mainly on project and programme management. Process management is mentioned only occasionally and then in comparison to or complimentary to project and programme management.

Management Is a Balancing Act

People in organisations are increasingly expected to react quickly, flexibly, effectively, creatively and efficiently to issues and stimuli from their environment. For many years, the more traditional organisations of the major conglomerates such as the car industry, government, banking and the chemical industry, served as role models for all other organisations. But times have changed and they are no longer the only exemplars. Nowadays, organisational inspiration also comes from professional service organisations such as advertising bureaux, policy departments, think tanks, consultancy bureaux and the editorial teams of newspapers and television programmes.

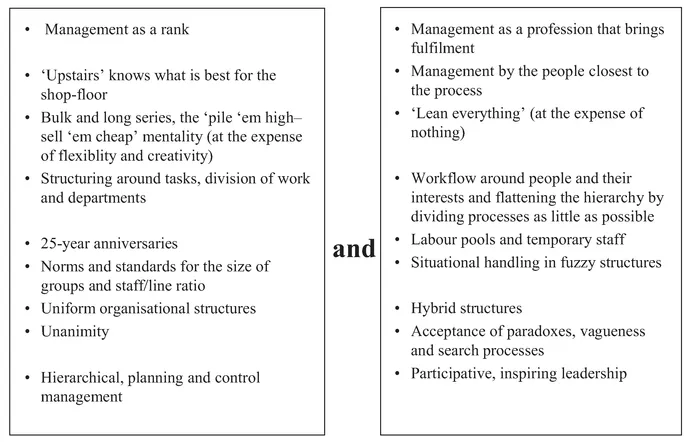

Management and organisation is no longer a question of this or that, but sometimes this and something else. A variety of developments are taking place within and between organisations: between an innovation centre and a call centre, for example; at other times within a single organisation, the super-friendly front-office staff and the excellent operational staff in the back-office. There’s no universal right or wrong in this. The organisation and management method depends on the demands of the environment, management’s vision on organisation, staff wishes and competencies, technological requirements and such like (see Figure 1.1).

We recognise several of these and-and considerations to be more specific to projects and programmes, namely:

- project or programme managers who can turn their hand to anything, and project or programme managers who have knowledge of the product, service, technology and/or market;

- projects based on energy, passion, learning moments and involvement, and projects based on rational planning and monitoring;

- programmes as a collection of activities managed by an improvising director, and programmes that are managed according to the relationship between goals and efforts.

This teaches us that there is no one ideal way to organise – not of the whole organisation, part of the organisation, or project or programme team. It all depends. But to be able to communicate with one another it is important to use clear, unambiguous terminology and methodology about how projects and programmes should be approached and managed. The existence of terminology and methodology alone is not enough: they must mean the same thing to everybody. Those involved must live the words and the spirit behind them instead of just slavishly following ubiquitous formats and handbooks.

Figure 1.1 Organisational trends

Increasingly, we see assignments that by their very nature cannot be assigned to any one organisational unit (group, department, division) and cannot be executed in accordance with previously determined standard procedures. These assignments – vital to the organisation – contain so many new elements that people in the organisation are unable to fall back on their previous experience. To be able to complete these assignments satisfactorily, you need to call on the knowledge of those who normally participate in other work processes. They are expected to leave their routines and participate in an assignment that is not part of their daily work.

Unique Assignments Can Be Classified in a Variety of Ways

People in organisations are regularly confronted with new situations to which they have no answer: a customer wants something new, the government introduces new legislation or the competition brings something new onto the market. Other causes lie within the organisation itself. Someone senses a new opportunity, a new product or service is developed or a new policy has to be implemented.

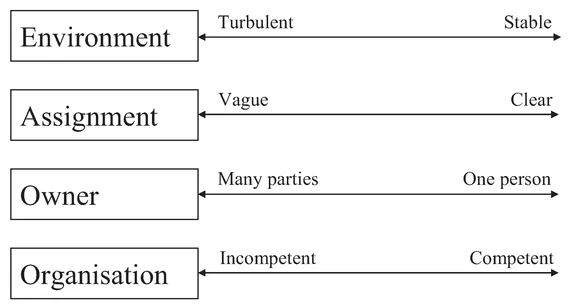

These new situations can be classified with the help of a number of dichotomies. A classification such as this can be useful when determining who is best qualified to lead those charged with carrying out this assignment. The classification of a unique assignment is also useful to staff them effectively, to determine the most appropriate method, to put in place the correct intervention method and to facilitate the carrying out of good risk analysis. Roughly 80 per cent of unique assignments can be classified using the four following dichotomies: stable or turbulent environment, concrete or vague assignment, adequate or inadequate ownership, and complete or incomplete operational organisation (see Figure 1.2).

Stable or turbulent environment

Figure 1.2 Several dichotomies to classify unique assignments

In a turbulent environment nobody really knows what will happen and what developments will take place. Parties often join a turbulent environment without warning while others pull out just as quickly. Coalitions between stakeholders come into being and disappear and financial sources are unknown. A turbulent environment is unknown and unpredictable, as is the amount of support for any assignment.

On the other hand in a stable environment relatively few changes occur at any given time, and any that do are easily predicted. The boundaries between the assignment and its environment can be described clearly and the assignment enjoys broad support.

Clear or vague assignment

The problems, goals or direction of a vague unique assignment are unknown. Many such assignments are often (politically) more sensitive because of the extra risks that the lack of direction attaches to them. These risks are the result of the techniques or the solution being unknown quantities or unknown technical feasibility. Finally, when the question of staffing and stakeholders arises, unique assignments are often vague because of their extremely complex character and long history.

In a clear environment the problems, goals and results are known quantities This means that the outcome of a clear unique assignment is clearly specified, defined, feasible and achievable. The risks of a clear unique assignment are known and accepted and the assignment is feasible and easily managed.

Adequate or inadequate ownership

When an assignment is owned by a number of representatives from more or less autonomous parties, we can describe this as being inadequate. In situations such as these, each of the parties has part of the required authority, means and motivation – and it’s usually the part that best serves their own interests. However, none of them is able to force the issue. This usually leads to protracted negotiations instead of adequate cooperation. In some unique assignments no one even seems to know who the owner is.

Assignment ownership is classed as adequate when the project is assigned to someone along with the correct tasks, responsibilities and authority. This one individual should have the authority, means and motivation required for the unique assignment. They are willing and able to force the issue. They also have the required competencies of knowledge, skill and behaviour at their disposal.

Competent or incompetent organisation

In organisations that are not competent for unique assignments there is a Babel-like confusion between the staff involved around the central goals, concepts and themes. The staff have little experience of cooperation but are experienced negotiators. They lack the knowledge and skills to tackle unique assignments successfully. There is little sense of urgency, only a tenuous bond with the assignment, fierce competition about areas of responsibility and little desire to think and work together.

A competent organisation for a unique assignment is one that is staffed by people who know how to tackle such assignments and have the knowledge and enthusiasm to do it. The staff have the skills and competence to complete it and are willing to work together. They also have a sense of urgency, understand the importance of the unique assignment and the desire to bring it to a successful conclusion.

Assignments that score more towards the left-hand side of the sliding scale for each of these dichotomies require greater improvisation. Process management may then be the more appropriate method. Programme management is used when the score is more towards the middle. Project management is used when all the scales are more or less aligned towards the right-hand side.

Different Ways of Working and Managing

Projects and programmes are characterised by their temporary nature, which makes it hard to fall back on existing tools. Unique assignments cannot be carried out using previously determined standard procedures. Unique assignments include: developing an information campaign, improving customer orientation, the development and introduction of new regulations, increasing market share, compiling a brochure for a foundation, introducing a new management system, reducing feelings of insecurity and introducing a patient follow-up system. They are also usually too important to tackle using an improvised approach. These assignments, regarded by those concerned in the organisation as important, contain many new elements making it impossible for them to fall back on previous experience and procedures.

Some organisations (such as architects, engineers, research and consulting bureaux) owe their existence to repeatedly carrying out other people’s unique assignments. Other organisations are formed temporarily to carry out just one major assignment, only to be disbanded when that assignment is completed.

Yet other organisations exist only to produce exactly the same product or deliver exactly the same services year in, year out. This last type of organisation is characterised by routine processes, strictly defined tasks and that everyone knows exactly what their job is. This does not mean that this type of organisation cannot be confronted by new unique assignments. Imagine, if you will, the development of a new coffee machine, the introduction of a new information system or implementation of a major reorganisation. Project management, and in certain cases programme management, are useful tools for achieving these ends. But before looking at this in more detail, we will begin by looking at other recognised work forms.

There are various possible approaches to working of which improvisation and routine – seldom to be f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 You Have to Choose the Right Approach

- 2 Organising for Projects and Programmes — The Approach

- 3 Organising All Involved — Checklists

- 4 Leading Your Team — The Approach

- 5 Helping Team Members Work Together — Checklists

- 6 Managing Your Project — The Approach

- 7 Initiating/Starting Your Project — Checklists

- 8 Executing Your Project — Checklists

- 9 Managing Your Programme — the Approach

- 10 Starting and Executing Your Programme — Checklists

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access 59 Checklists for Project and Programme Managers by Rudy Kor,Gert Wijnen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.