![]()

Chapter 1

Organizational Safety Culture

Sallie J. Weaver and Hanan H. Edrees

Contents

1.1Introduction: Organizational Culture and High Reliability

1.2What Is Organizational Culture?

1.2.1Definitions of Safety Culture

1.2.2Models Examining the Inputs, Emergence, and Outcomes of Safety Culture and Climate

1.2.2.1Reiman’s Layers of Culture Model

1.2.2.2Zohar’s (2003) Multilevel Model of Safety Climate

1.2.2.3High Reliability Organizing and Safety Culture: The 3 E’s Model

1.2.3Patient Safety Culture and Outcomes

1.3Leadership and Organizational Culture

1.4Tools for Measuring Patient Safety Culture

1.4.1Patient Safety Culture and Climate Assessment Tools in Healthcare

1.5Interventions and Strategies for Building Cultures of Patient Safety

1.6Barriers to Developing and Sustaining Safety Cultures

1.7Application: A Case Study of Transformation and Building a Culture of Resilience After the MERS–CoV Outbreak at the Ministry of National Guard Health Affairs (NGHA), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

1.7.1Background

1.7.2The MERS–CoV Outbreak

1.7.3Transformation and Building a Culture of Resilience

1.8Conclusions and Lessons Learned

References

The only thing of real importance that leaders do is create and manage culture.

Edgar Schein

Professor Emeritus, MIT Sloan School of Management

1.1 Introduction: Organizational Culture and High Reliability

Healthcare leaders have a lot to learn from organizations that achieve outstanding levels of safety and performance despite operating in high-risk environments. Such organizations include oil and gas production, nuclear power, aviation, and military operations. Originally defined by organizational scholars Karlene Roberts, Todd LaPorte, and Gene Rochlin as “high reliability organisations” (HROs; see Chapter 5), these organizations have mastered the ability to anticipate the unexpected, adapt, and produce reliably safe, high-quality outcomes despite the significant complexity and inherent risk in their work (Rochlin et al. 1987). HROs offer a benchmark for healthcare leaders and care delivery systems. While healthcare shares levels of complexity and risk with these industries, patients continue to experience preventable harm and patients and their loved ones still report uncoordinated, suboptimal care (Aranaz-Andrés et al. 2011; Bouafia et al. 2013; The Joint Commission 2015; Wilson et al. 2012; Jha et al. 2010).

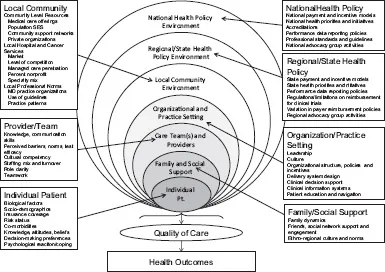

Thanks to theoretical and empirical work by Kathleen Sutcliffe, Karl Weick, Tim Vogus, and others, we now have an enriched understanding of how HROs function, learn, and adapt, and more nuanced insights into the underlying assumptions and values that shape how their leaders and frontline team members approach their work (Weick and Sutcliffe 2007; Weick and Sutcliffe 2015). These theories emphasize that the pathway to reliably safe outcomes involves: (1) practicing a series of cognitive and behavioral habits that can be identified as mindful organizing; (2) reliability-enhancing work practices; and (3) actions that enable, enact, and elaborate a culture of safety and a climate of trust and respect (Sutcliffe et al. 2016). While contextual factors at multiple levels interact to influence care processes and outcomes (see Figure 1.1), research has shown that organizational culture influences a broad range of issues including (1) the situations and cues that clinicians, staff, and administrators perceive or interpret as indicators of potential harm; (2) a willingness to speak up with concerns, questions, and ideas about opportunities for improvement (also known as a sense of psychological safety [Nembhard and Edmondson 2006]); and (3) motivation to participate in improvement work. Given the foundational role culture plays in developing the habits and practices of mindful organizing and reliably safe outcomes, it is fitting to begin this text for healthcare leaders with a chapter dedicated to organizational culture. Chapter 5 provides an in-depth discussion of other aspects of HROs and related principles.

Figure 1.1 Multilevel model of contextual factors influencing care delivery. (Adapted from Taplin, S. H., et al., JNCI Monographs, 2012, 2, 2012.)

We provide an overview of the state of the science and practice related to patient safety culture and leadership strategies for strengthening culture and addressing challenges associated with punitive cultures. We also discuss practical issues related to assessing patient safety culture in practice. First, we describe the fundamental definitions and models of organizational culture and related concepts of patient safety culture and climate in the healthcare context. We discuss the antecedents and factors that influence how cultures emerge, develop, and change over time, as well as the outcomes linked to culture in the healthcare context. Third, we relate these overarching concepts to the notion of mindful organizing and draw insights and guiding principles from research on high reliability organizing. Finally, we summarize the existing evidence on the leadership strategies and interventions thought to influence organizational culture.

1.2 What Is Organizational Culture?

Culture can be defined as the set of shared beliefs, assumptions, values, norms, and artefacts shared among members of a given group such as an organization, profession, department, unit, or team (Ouchie and Wilkins 1985; Pettigrew 1979; Schein 2010; Schneider et al. 2013; Guldenmund 2000). Organizational culture reflects the learned tacit set of assumptions and related behavioral norms that members of a given organization would describe as “how we do things here,” “why we do these things in this way here,” and “what we expect around here” (Schein 2010; Weick and Sutcliffe 2007). Organizational culture colors the lens through which members formulate their mental model of “the right thing to do” in a given situation and their perceptions of which types of decisions or actions may be praised and which may be frowned upon. It is the compass that clinicians, staff, and administrators use to guide their behaviors, attitudes, and perceptions on the job (Zohar and Luria 2005; Schein 2010). This is why culture is a critical aspect of developing and sustaining reliably safe care and why it is important for healthcare leaders to mindfully manage the culture in their organization, department, unit, or team as part of their work.

1.2.1 Definitions of Safety Culture

HROs develop strong safety cultures (Bierly 1995; Weick and Sutcliffe 2015) and emphasize collective accountability for identifying and addressing system issues that contribute to undesirable outcomes (Weaver et al. 2014). Safety culture refers to one facet of a larger, overarching organizational culture. While multiple definitions exist, safety culture can be defined as “those aspects of organisational culture which impact attitudes and behaviours related to increasing or decreasing risk” to organizational members and to the individuals and communities served by the organization (Guldenmund 2000, p. 250). An organization’s overarching culture tends to encompass aspects such as how internally versus externally focused an organization tends to be and the degree to which flexibility and discretion are valued relative to factors such as stability and control (Cameron and Quinn 2011). Within that larger culture, the concept of safety culture focuses specifically on the way that risk, safety, and occupational health are approached and valued within a given organization or group (Guldenmund 2014; Guldenmund 2000). The related construct of patient safety culture further sharpens this focus and refers to the values, beliefs, assumptions, behavioral norms, symbols, rites, and rituals specifically related to patient safety (Waterson 2014; Guldenmund 2014). Patient safety culture is a multidimensional concept that generally manifests in (1) communication patterns and language related to patient safety; (2) feedback, reward, and corrective action practices related to patient safety; (3) formal and informal leader actions and expectations related to patient safety; (4) teamwork processes and collaboration norms; (5) resource allocation practices; and (6) error detection, correction, and learning systems (Schein 2010). Finally, the related but distinct concept of patient safety climate refers specifically to clinician and staff perceptions of the more observable aspects of patient safety culture including policies and procedures and the degree to which leaders and colleagues prioritize patient safety in their daily work (Zohar 2010; Zohar et al. 2007; Waterson 2014). For parsimony, we will use the term patient safety culture for the remainder of this chapter, bearing in mind the nuanced differences between these concepts despite the fact that they are often used interchangeably in practice.

It is important to emphasize that patient safety culture is only one aspect of an organization’s overarching culture and that organizational attitudes and norms related to patient safety are shaped, at le...