![]()

Best practice 1

Maintain transparency to clients and trainees

Those involved in Training and Development acknowledge a framework of best practices that provides structure for their training and consulting.

Trainers and consultants should have readily available standards to which their activities can be evaluated by participants. Language should include demonstrable benchmarks.

Trainers and consultants must abide by a documented code of ethics that is easily obtainable by clients and assessment groups.

Transparency is a two-way street that needs to be handled authentically by all parties in a communication training relationship. Consultants and trainers must understand expectations of clients and trainees. Conversely clients and trainees must understand expectations and limitations of those involved in communication training and development. Too often, both parties are involved (sometimes unknowingly) with bait and switch techniques. The first chapter, “Mobilizing a client for change” shows how trainers and consultants can obtain and build “Request for Proposals” that use clear frameworks to clarify expectations. The next chapter, “Communication training’s higher calling”, demonstrates how a civic frame can be used both to promote transparency and elevate the value of services. Finally, “The F-word changes a circular message” demonstrates even controversial frames have extended value when mutual interests are clearly expressed.

![]()

Chapter 1

Mobilizing a client for change

Best practices for proposing training

Jennifer H. Waldeck

Abstract

The ability to write a clear, persuasive, thorough, and marketable training proposal is the foundation for training that serves both client and trainer. This chapter details how to develop responses to formal Requests for Proposals (RFPs) common throughout government and industry. However, many proposals lack strategy or influence. Procedures, techniques, and considerations are provided to enhance professionalism for both novice and experienced trainers as well as to advance their submission response rate.

The proposal is the primary opportunity for a trainer to show an organization why he or she is best suited for the work, describe the training plan, provide a timeline and budget for the project, and to formalize a relationship with the client. It is critical for authentic and transparent training. Yet, trainers create proposals that often go unnoticed, unread, and/or unfunded. Many trainers are shortsighted in their thinking about what the proposal represents, and view it as little more than a formal means to obtain work. As a result, these important documents often lack strategy and influence. At its best, the proposal is a powerful tool for persuading clients to begin the progressive trajectory that great training makes possible—a path toward organizational development and improvement.

An effective training proposal defines the scope, objectives, rationale, and cost of a training intervention. It is well-organized, well-written, and, ultimately, highly persuasive. Further, the best proposals are highly client-centered. Each element must be written with careful attention to the unique nature of the client organization’s culture, people, communication climate, structure, politics, and system (both internal and external). This chapter provides perspective on how to plan, write, and deliver proposals that will help the trainer win work, and that represent the first step toward influencing clients to make productive changes. This is essential to establishing fit with what the trainer offers and what the client desires.

A training proposal should address six primary topics (Waldeck, Plax, & Kearney, 2016):

The trainer’s credentials, experience, and technical ability to deliver the proposed services.

The objectives of the proposed instruction.

A detailed description of the training plan – the content, training methods, and assessments that the trainer is proposing based on an individualized client needs assessment (Jorgensen, 2016; Plax, Waldeck, & Kearney, 2016).

A timeline for carrying out the training along with logistical details of project management for multi-phase training plans.

The estimated costs and expenses associated with the project.

The method(s) for evaluating the effectiveness of the proposed plan.

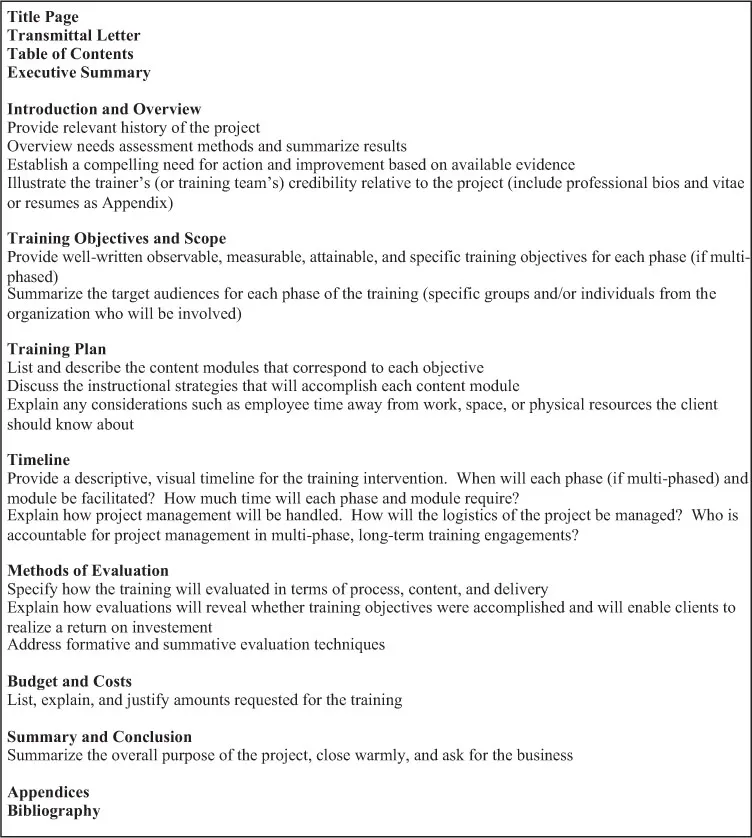

Example 1.1 features a flexible outline that can be adapted for most training proposals (Waldeck et al., 2016), into which these six topics can be situated. To produce a proposal that will have the greatest short- and long-term impact, trainers should spend an appropriate amount of time assessing the client’s needs and collecting relevant data about the organization.

Example 1.1 Suggested Table of Contents for training proposals.

The proposal’s backstory: Organizations and their training needs are rarely simple

Understanding an organization’s training needs and how to best address them in a proposal requires a sophisticated understanding of organizing and organizational communication in general, and an ability to assess the specific organization relative to the expressed need – sometimes with little direct access. Organizations are complex structures; their needs rarely simple. For example, a client once requested a proposal for a four-hour customer service training session that would involve front line employees. Driving his perception of the need for this course were negative online customer reviews. To him, the solution was simple and straightforward. But when I began asking questions and observing the underlying informal organization, I realized that although what he was asking for was appropriate, even more critical was work with middle management. The front line experienced morale and motivation problems due to lackluster in-store management and oversight. If we implemented only front line customer service training, we would be patching a deep hole instead of filling it in. The question then becomes how do trainers learn the nature and extent of the ‘holes’ that they are working with and expected to fix? This backstory to the training proposal begins with how the trainer and client find one another.

The nature of the proposal is dependent, to an extent, on how the trainer came to bid on the job – in response to a Request for Proposal (RFP) or after a systematic needs assessment. An RFP is an invitation to qualified organizations or individuals to bid for specific work, typically without the benefit of a thorough needs analysis.1 For instance, in 2016, working with a consulting group, I responded to a RFP from a U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) agency. The project involved developing training on communication in virtual team environments. Like many RFP-driven proposals, this proposal was very difficult to create. I had limited experience consulting with this particular agency. Although others on the team had worked with different units within DOD for many years, they had not worked with this particular project manager or target audience. Thus, we were constrained in our ability to understand the politics of the agency and the backstory of the RFP easily or accurately. We had to base our assessment of the client’s needs strictly on the very general RFP. In addition to providing the qualifications that consultants had to meet (e.g., in terms of education, experience, and publication history), this document simply stated that the agency was requesting bids for a 10-hour curriculum on virtual teamwork and communication that could be delivered online or in an instructor-led environment.

From this example, you should see that trainers writing proposals in response to a published RFP have access to the limited, general information provided in the request. The inexperienced trainer will provide a generic response to a generic RFP. Conversely, the seasoned trainer knows that organizational culture, politics, structure, and personalities all interact to create the needs expressed in the RFP (Ross & Waldeck, 2016). An effective trainer networks with organizational insiders and does the kinds of informal research necessary to contextualize the often-vague contents of an RFP. This resource-intensive, behind-the-scenes work is essential for creating an influential proposal. My team ultimately won the contract to develop the virtual team communication course. However, we had generated many previous proposals for other agencies within the DOD that were unsuccessful because we had not yet built the connections, knowledge, and client-specific expertise necessary to understand the complexity of the needs expressed in the RFPs we had received. Thus, our proposals did not stand out. Over time, we sought a great deal of feedback on proposals submitted but unfunded and work completed, and built relationships that helped us develop the kind of understanding necessary to be successful.

When an RFP is issued, the client typically has a designated official who will respond to consultants’ queries. However, the insight that contact offers is nothing like the type of information trainers can acquire through a needs assessment and by establishing an ongoing communication relationship with a prospective client. Thus, in contrast to the DOD bid, most of the work that I do is for clients with whom I have pre-existing relationships. Aware of my expertise, interests, background, and experience, these people approach me with a particular need. Even with well-established relationships, clients may require a written proposal and often question or resist aspects of my recommendations. My proposals must be persuasive, well-supported, well-written, and strategically aimed at the organization and its needs. I will ask the prospective client for the opportunity to speak with key stakeholders, and to do a formal needs assessment when appropriate (Jorgensen, 2016; Plax, Waldeck, & Kearney, 2016). These conversations and research methods allow me to create an effective, targeted proposal. In the next section, I discuss the strategies that underlie the process I follow for writing proposals for training and other consulting work.

Strategies for creating a successful proposal for training

Approach the proposal as persuasion

Proposals are, first and foremost, persuasive messages. They allow trainers to establish their credibility, convince clients of the urgency of organizational needs and problems, propose workable solutions, and persuade readers to accept recommendations. Influential proposals enable trainers to present themselves as a valuable asset to the organization who recognizes its needs – a partner that is able to make appropriate recommendations for addressing them. As with any persuasive message, readers of training proposals will fall into three groups – those who (1) already support the plan, (2) are neutral or undecided/uninformed about the issues addressed in the proposal, and (3) disagree with the need for training or with the recommended training solutions. As we will explore in this chapter, the persuasive proposal must be written for each of these audiences. After reading the proposal, previously agreeable readers should be even more motivated to accept the trainer’s recommendations, neutral or undecided people should be more knowledgeable and invested in the issue, and disagreeable decision makers should feel respected, unthreatened, and more open to a reasonable amount of change. With this last group, the trainer must be cautious not ask for too much commitment at once to any issue or recommendation that the reader resists; rather, the training proposal should acknowledge potential objections to the plan, propose incremental change, and provide ample evidence of the plan’s feasibility. Be very careful not to create resistance by offending readers with an approach that suggests that their organization is behind the times, uninformed, noncompetitive, or poorly managed (even if you believe that any of these conditions are true).

As with any persuasive message, the trainer should support the project in general and each recommendation in particular with clear, convincing reasoning. Link each training recommendation to one or more of the project objectives. Substantiate the proposal with needs assessment data, and wherever possible, with a theoretical or research-based rationale from the literature. My own training and consulting work is influential with organizational clients because it is grounded in credible, rigorous research and theoretical frameworks (Waldeck, 2016). But I write proposals in a style appropriate for the target audience – organizational decision makers who may not fully understand these research-based and theoretical approaches but seek positive change. Be sure to use relevant language to translate areas of your expertise that might be unfamiliar to the client. Effective trainers make their recommendations familiar and consumable to diverse readers in applied settings.

Persuasive proposals should conclude with specific action steps for the organization to take. In other words, ask for the work. Once you have created a sense of urgency surrounding the organization’s needs and proposed a relevant and realistic solution, you must be clear about what the client needs to do in order start a formal working relationship with you. Leave the reader confident and comfortable that you will be able to credibly and reliably assist this organization in making needed improvements.

Communicate frequently with the client

Whether face-to-face or mediated (e.g., video calling or conferencing, e-mail) (Stephens & Waters, 2016), frequent, in-depth communication with clients results in the best proposals. This point is critical. Trainers should work closely and check in with the client as they specify objectives for the training, create the instructional design plan, and develop a budget. Working closely with the client at this stage ensures buy-in and a realistic proposal that is aligned with the client’s needs, expectations, and available resources. To build the best possible relationship with contacts, practice active listening, rapport-building skills, verbal and nonverbal immediacy, and affinity seeking strategies (Beebe, 2016).

The more engaged the client is in the entire process, beginning with the formulation of the proposal, the more likely the client will be satisfied with the proposal the trainer generates, and ultimately, with the results of the training engagement. If the client is disengaged, or if the trainer does not communicate with the client during the formulation of the proposal, the trainer will have a difficult time getting buy-in and approval. Clients that are less involved in the early stages of the trainer’s work tend to be more critical than engaged clients because they lack an appreciation of the process and product. Conversely, clients that give input into the proposal already feel a sense of ownership relative to the training and its potential benefits.

Some clients may want to be over-involved and attempt to control the direction of the work. For instance, a manager of a department within a large city government contacted me with a very specific training request. This client, concerned about costs and a sensitive political climate inside his organization, insisted on writing the description of the program, as well as the training objectives he wanted me to build my training plan around. I knew that the program I would propose should incorporate his input, but that I would need to carefully probe and assess his assertion that there were no other issues to address. The tactful trainer considers the client’s concerns and addresses them in the proposal, but still makes recommendations based on an objective assessment of the organization’s needs.

Whether clients are withdrawn or domineering, the best consultants leverage and manage their interactions with them, but do not rely solely on their input. Trainers should listen carefully, educate their clients about the training process, ask good questions, seek additional input from within the organization, and use the information they gather to write a strong proposal. Treat everything you observe and hear as valuable data. Working with experienced mentors in the fields of training and organizational consulting, I learned very early the importance of integrating clients into my work beginning with the proposal stage. Doing so gives them a feeling of ownership and investment in that work and gives me greater insight into the organization. As a result, the trainer has a heightened chance of successful engagements, additional contracts, and satisfying, long-term relationships.

Write strategically and well

Trainers must write their proposals strategically, with a great deal of attention to detail. First, this means that the document must be tailored to the specific client for which it is being written. Trainers must write their proposals with the knowledge that multiple people inside the organization will read them. I ask my primary contact on any engagement who will be receiving a copy of the proposal, and who the decision ...