![]()

CHAPTER

1 | The meaning, origins and contribution of the humanities |

Matthew Arnold, 1822–1888, Chief Inspector of Schools (quoted by Conway, 2010: 49).

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter you should be able to:

• define what is meant by the humanities;

• outline the origins and development of the humanities;

• recognise the contribution of the humanities in promoting positive values; and

• reflect upon the importance of history, geography and religious education (RE) in children’s all-round development.

What do we mean by the humanities?

Put simply, the humanities are academic disciplines that explore human culture and experience. This broad definition reflects the diverse studies of the humanities in the modern age. For instance, university students who follow a ‘medical humanities’ programme consider the therapeutic value of art, ethical issues associated with plagues in the past, and the influence of a family on a person’s health and well-being (Evans and Finlay, 2001). Elsewhere, ‘digital humanities’ students might ask questions about economic, cultural and social challenges posed by ICT innovations such as e-books (Hockey, 2008). The huge scope of the humanities is well illustrated by the coverage within the British Humanities Index, an online database of articles in over 370 internationally respected humanities journals and weekly magazines published in the English-speaking world. The major categories include: antiques, archaeology, architecture, art, cinema, current affairs, education, economics, environment, foreign affairs, gender studies, history, language, law, linguistics, literature, music, painting, philosophy, poetry, political science, religion and theatre. It is not surprising, then, that Adams (1976) referred to ‘the humanities jungle’ in trying to pin down the content of the humanities. He adopts a very broad definition in terms of subjects (Box 1.1).

BOX 1.1 DEFINITIONS OF THE HUMANITIES

That group of subjects which is predominantly concerned with men and women in relation to their environment, their communities and their own self knowledge.

Schools Council (1965: 14)

The ‘humanities’ includes history, possibly geography, the remnants of classical studies, some aspects of English and modern languages, religious education and so on.

Adams (1976: 11)

Part of the primary curriculum that is concerned with individual human beings living and working in particular places and linked together with groups and societies, past and present.

Blyth (1990: 1)

A collective term for a range of academic disciplines or fields, all of which draw upon a knowledge of the development, achievements, behaviour, organisation, or distribution of humanity.

Wallace (2008: 132)

The study of the myriad ways in which people, from every period of history and from every corner of the globe, process and document the human experience.

Stanford University (https://humanexperience.stanford.edu/what)

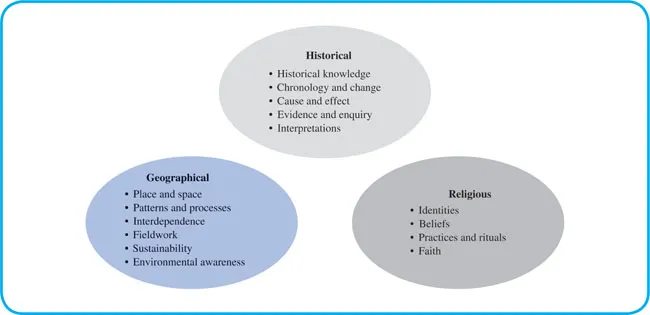

In subject terms, one way of looking at the humanities is to see how they are different from other branches of knowledge, such as the sciences. Those working within the humanities are not necessarily seeking a single correct answer and are more likely than scientists to accept ambiguities and various interpretations arising from beliefs, texts and practices. For Black (1975), the humanities are distinctive from the ‘hard’ sciences because they are not concerned with ‘neutralising’ differences in pursuit of objective truth. He adds that students of the humanities want to go beyond presenting human perspectives by critically engaging with their subjects. The major building blocks for primary humanities covered in this book are shown in Figure 1.1.

REFLECTION

• In 2018 the University of North Carolina launched, as part of its outreach programmes, a Humanities Happy Hour in a public bar so that students and lecturers could informally discuss humanities issues with locals. Philosophy in Pubs is a similar venture. What might be top of such an agenda in the UK at present?

What are the origins of the humanities?

The humanities have a long history. More than 2,500 years ago, the classical Greeks had a new conception of humanity and what the human mind was for: namely to reason, seek out patterns and, above all, ask questions (Kitto, 1951). Socrates (c. 469–399 bc), one of the leading philosophers, proclaimed that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’. Socrates believed that by asking questions, listening to responses and then raising further questions (the Socratic Method) teachers could reach the heart of what students believed. For Socrates, it was important for people to know what they were doing, why they were doing it and whether their actions were the right things to do. According to Hughes (2011: xix): ‘We think the way we do, because Socrates thought the way he did’.

The study of history in Western civilisation began with the ancient Greeks. They produced the first historians, who asked such basic questions as ‘Why did events happen when they did?’ The word ‘history’ (from the Greek historia, meaning ‘enquiry’ or ‘research’) is derived from the writings of Herodotus (c. 484–425 bc). Considered ‘the father of history’, Herodotus was the first to document and analyse the causes of a war, the Persian War: ‘Herodotus made it a rule for historians to explain the events they told’ (Finlay, 1981: 158). Most significantly, he established the view that history should not favour one side or the other, since this would obscure truth (Warren, 1999). But it was another Athenian historian, Thucydides (c. 460–400 bc), who ‘wrote true history’ (Warren, 1999: 18). He probed beyond recollections of battles by scrupulously examining eyewitness accounts of military generals.

Geographical education in European experience also began with the ancient Greeks. Homer’s Odyssey can be seen as the first travel book, composed in the eighth century bc. Greek librarian Eratosthenes (c. 276–196 bc) was the first to use the word ‘geography’ (literally ‘writing about the earth’) in his attempt to produce an accurate map of the world. He thought that the earth was a sphere and calculated (reasonably accurately) its circumference and the amount of habitable land. He also developed the concept of latitude. The Greek Strabo, writing in the first century ad, was the first to justify the usefulness of geography ‘not only for politics and war, but also in giving knowledge of the heavens and of things on land and sea, animals, plants, fruits and of all that is to be seen in different regions’ (quoted by Walford, 2001: 4).

The vibrant Athenian democracy involved debate and openness, whether in the assembly, market-place or the secondary ‘schools’ (from the Greek skhole, meaning ‘a place of leisure’). These schools were aimed at the sons of wealthy citizens that had completed elementary schooling and had time on their hands to follow a course in liberal education – liberal in the sense that it was for free men, not slaves or servants, and was non-vocational in nature. They were run by a paidagogos (from which we derive pedagogy or the craft of teaching), or master teacher. He taught philosophy, politics, good manners and persuasive speaking (rhetoric) so that young men could become accomplished individuals, making good use of their leisure time (Finlay, 1981). The students learnt that traditions, beliefs and myths were not fixed doctrines to be handed on to the next generation but that they were to be questioned – this was nothing short of ‘a revolution in education’ (Finlay, 1972: 68).

The Greek spirit of enquiry was given a practical edge by the Romans. The very word ‘education’ comes from the Roman home, for the Latin educare referred not to schooling but to how children were brought up and trained by their parents who ‘drew out’ their thinking (Bonner, 1977). The Romans generally appreciated that young children needed to read, write, count, weigh, measure and calculate. At a more advanced level, Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 bc) (Photo 1.1) suggested a training programme for public speakers based on the ‘studies of humanity’ (studia humanitatis), which included all branches of learning. Cicero contrasted the ‘humane and cultivated’ life with the ‘savage and barbarous’, and a study of the humanities brought about the former. Castle (1961) suggests that the curriculum included Latin grammar, history, poetry, rhetoric, philosophy and music. These subjects prompted students to think clearly and judge critically. Our word ‘critic’ comes from the Greek kritikos, which originally applied to students who were critics of literature – the more able students became judges (krites) of literary quality (Bonner, 1977: 48–9).

The Greeks and Romans provided the blueprint for the education of the elite in Britain over the centuries. Classical writings were fused with Christian teaching to form the basis of the grammar and public school curricula through to the twentieth century. These schools aimed to provide learners with the intellectual skills and moral fibre expected of leaders. As Musgrave (1970: 254) observed: ‘The British upper classes were convinced that a thorough grounding in the classics was the best training for a country’s administrators, statesmen and military leaders’. The nineteenth-century Chief Inspector of Schools, Matthew Arnold, whose words open this chapter, advocated that children should be introduced to ‘the best that has been thought and said’. Arnold demonstrated the classical humanist commitment to initiating children into the ‘best’ of cultural heritage. Michael Gove, former education secretary, made much of reclaiming Arnold’s vision; for instance, he supported the sending of a free copy of the King James Bible to every state school in England, on the edition’s 400th anniversary, so that they can access the best of Britain’s cultural heritage. He favoured the virtues of a classical education, arguing that an ‘audience would be gripped more profoundly by a passionate, hour-long lecture from a gifted thinker which ranged over poetry and politics than by cheap sensation and easy pleasures’ (Shepherd, 2010; Vasagar, 2011).

How did the humanities develop in the curriculum?

As separate subjects, history and geography first featured in the grammar school curriculum during the sixteenth century (Watson, 1909). Geography, along with the sciences and modern European languages, became important to the merchant and manufacturing middle classes. Since the earliest church schools of the post-Roman era, the education of the masses had focused on basic skills and religious instruction. History and geography became part of the first national curriculum for elementary schools introduced by the state in 1862. Even then, the substance of these early history and geography lessons focused largely on rote learning of kings, queens, battles, capes and bays, amounting to little more than ‘adjuncts to biblical instruction’ (Marsden, 2001: 33). Geography and nature study testified to the glories of God’s creation, while history served moral purposes such as the need for obedience.

Religious Instruction (RI) was prominent on the school timetable through to the mid-twentieth century. In England and Wales, the 1944 Education Act conceptualised religious education (RE) as a combination of religious instruction and collective worship (Copley, 1997). The 1988 Education Act required local authorities in England and Wales to produce their own agreed syllabus for RE, overseen by a standing advisory council on religious education (SACRE). Local authorities are also required to appoint an occasional body called an agreed syllabus conference (ASC) to review its agreed syllabus. However, schools designated as having a religious character are free to make their own decisions in preparing their syllabuses. The Education (Scotland) Act 1980 requires local authorities to provide religious observance in Scottish schools. Religious education and religious observance form part of Scotland’s Curriculum for Excellence, with schools and local authorities having the discretion to determine the content, frequency and location of religious observance. Similarly, in England and Wales, every locally agreed syllabus sets out what is to be taught in schools, although teachers’ planning is also supported by national non-statutory guidance materials (DCELLS, 2008c; DCSF, 2010a) as discussed in Chapter 9. Schools can decide when and how subjects are taught and the amount of time spent on each subject, but they are r...