Part I

Introduction

Alden Mahler Levine and Gregory Mahler

And as for Ishmael, I have heard thee; behold, I have blessed him, and will make him fruitful, and will multiply him exceedingly; twelve princes shall he beget, and I will make him a great nation. But My covenant will I establish with Isaac, whom Sarah shall bear unto thee at this set time in the next year.

Bereshit (Genesis) 17:20–21, JPS translation

…We covenanted with Abraham and Isma’il, that they should sanctify My House for those who compass it round, or use it as a retreat, or bow, or prostrate themselves (therein in prayer).

Holy Qur’an 2:125, Yusufali translation

Thus, in theory, begins the cycle of tension between Arabs and Jews.1 It may have been Isaac or it may have been Ishmael who was the favorite child and heir of Abraham (or, of course, it may have been neither at all). The fact remains that two peoples point to this millennia-old story as their “origin myth.” More importantly, two peoples point to the land bequeathed by the shepherd Abraham and call it their own.

Because this is not a religious text, but an academic inquiry into a modern political situation, this story cannot be the basis of our analysis or argument. Neither is it particularly useful to itemize the subsequent regimes in the region. As fascinating as the Babylonian, Assyrian, Greek, Roman, Old Kingdom, Caliphate, and Ottoman – in no particular order! – governments may have been, they will serve us as little more than a backdrop. In short: the portion of the Middle East currently known as Israel or Palestine has, for a very long time, been the object of a great deal of contention. Sometimes one group held power and sometimes another, and sometimes power was shared or contested by more than one group. Poised at the crossroads of three continents, Palestine has rarely known peace.

But the situation currently known as the Arab-Israeli conflict is a thoroughly modern and wholly political predicament. It is a story of international machinations, citizen rebellion, and (quite literally) the quest for world domination. And in its modern incarnation, the Arab-Israeli conflict has left a paper trail.

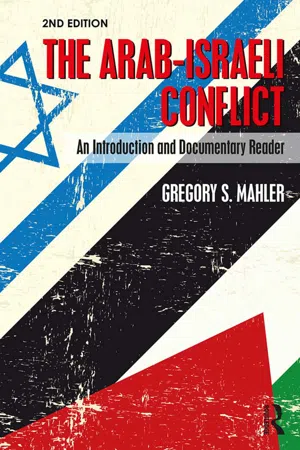

Map 1 Israel in the Middle East.

Source: Republished with permission of Wadsworth, a division of Cengage Learning from ‘Israel: government and politics in a maturing state’, Gregory Mahler, 1989; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

This text will allow the reader to analyze the Arab-Israeli conflict through the words of those who have lived it. From the publication of Der Judenstaat to the Road Map in the early years of the twenty-first century, these documents speak for the times and ideas they embodied. By placing them within their historical context, we hope to allow the reader to better understand the motivations of the authors.

In 1896, an Austrian journalist named Theodore Herzl wrote a volume that would prove to play a historically crucial role in world history, titled The Jewish State.

See reading #1, “Theodor Herzl, The Jewish State (1896)”

Herzl did not invent the concept of Zionism, but his book formalized a growing belief among Jews of the world about the need for a Jewish state. Anti-Semitism was an intense and apparently ever-present problem. In the decades dominated by emerging nation-states and the philosophies of self-determination and ethnic identity, the notion that the Jews too deserved a homeland – or a state2 – appealed to many people.

The precise location of the hypothetical Jewish homeland was far from a given. Although many Jews felt a religious tie to the land that today is Israel, the movement for a homeland was itself predominantly secular. In fact, many religious Jews considered it an affront to God for man to construct a Jewish state, rather than waiting for it to occur naturally when the Messiah arrived. Without a strong religious mooring, proposals for a location ranged from rural areas of Argentina to Uganda or the island of Madagascar.

See reading #2, “The Basle Program (August 30, 1897)”

Eventually the focus of the early Zionist movement did turn toward Palestine, at the time a part of the centuries-old Ottoman Empire, known as the “Sick Old Man of Europe” for its persistence even as it lost territory and its government’s hold became increasingly tenuous. The Ottomans had thrown their lot in with the losing side of the First World War and found themselves pitted against the United Kingdom, France, and Russia in that conflict. Moreover, it faced the insurrection of its Arab citizens. The ruler of Mecca at the time, Sharif Hussein bin Ali, saw an opportunity for self-rule at long last. Corresponding with Sir Henry McMahon, British High Commissioner in Egypt, Hussein felt assured of Great Britain’s support for Arab independence and threw his considerable influence behind the British objectives.

See reading #3, “The McMahon Letter (October 24, 1915)”

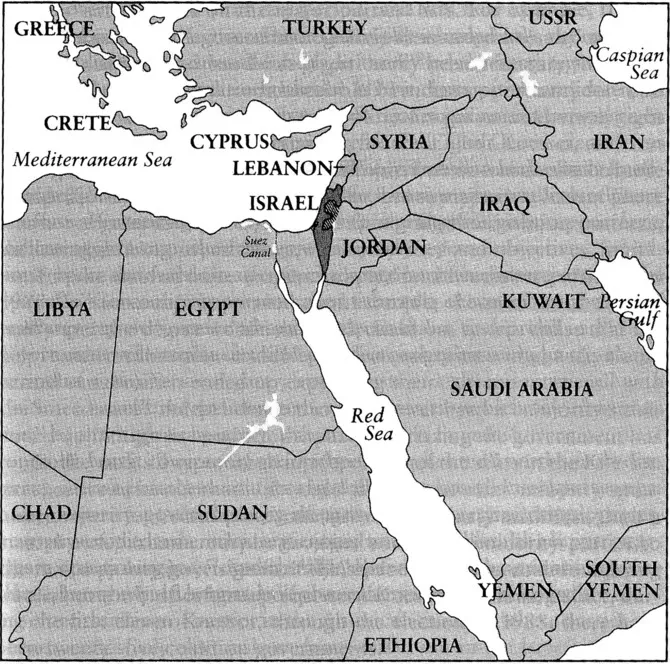

The Ottomans’ days were numbered, and the Ottoman Empire crumbled in the First World War, leaving huge swaths of formerly Ottoman territory in a governmental limbo. Into that vacuum stepped the newly dominant nations of Great Britain and France. Fiercely competitive throughout their modern histories, the former allies came prepared with the Sykes-Picot agreement, which had been secretly drawn up in negotiations between the two during the War. The agreement proposed to divide all former Ottoman lands into either French or British “spheres of influence.” The area known as Palestine was awarded to the British.

See reading #4, “The Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916)”

Map 2 The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916.

Source: Permission granted by the Institute for Curriculum Services (San Francisco) to reprint their map of the Sykes-Picot Agreement in this book. The original can be found at: www.icsresources.org/maps.

Over the next three decades, the question of who would permanently control Palestine was never fully settled. Both Arabs and Jews lobbied for influence and control over the land, and both felt they had been promised that control by the British government. The Balfour Declaration of 1917 implied a British goal of the establisment “in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people” – in but not exclusively comprising. The sons of Sherif Hussein pointed to the British promises to their father and demanded their fulfillment. And the British sought to control the valuable trade routes and resources of the Middle East for as long as possible.

See reading #5, “The Balfour Declaration (November 2, 1917)”

On January 3, 1919, Dr. Chaim Weizmann signed a political accord in the name of the Zionist Organization with the Emir Feisal, son of the Sherif of Mecca, within the framework of the Paris Peace Conference ending the First World War. In this agreement the Arabs promised to recognize the Balfour Declaration and said that they would permit Jewish immigration and settlement in Palestine. The agreement also included to support freedom of religion and worship in Palestine and promised that Muslim holy sites would remain under Muslim control. As part of the agreement the Zionist Organization said that it would look into the economic possibilities of an Arab state.

See reading #6, “The Weizmann-Feisal Agreement (January 3, 1919)”

Despite receiving a great deal of attention when it was announced, the Weizmann-Feisal agreement was repudiated by Arab leaders shortly after it was signed, and it was never implemented. Even as the debate raged on, Jews flocked to Palestine from Europe and North Africa, fleeing political tensions and escalating anti-Semitism. This Jewish population shift and government instability in Palestine led to riots and general disturbance.

See reading #7, “The White Paper of 1922 (June, 1922)”

In the period from 1920 to 1922 tensions in Palestine increased between the native Arab and immigrant Jewish populations, and both sides were unhappy with the way that the British were handling the situation. In 1922 British Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill issued an official White Paper – a formal governmental policy statement – that put forward on behalf of the British Government a more restrictive interpretation of the Balfour Declaration. The White Paper concluded that Palestine as a whole would not become a Jewish “national home” and suggested limitations on Jewish immigration to Palestine through the introduction of the concept of “economic absorptive capacity” into regulations governing Jewish immigration.

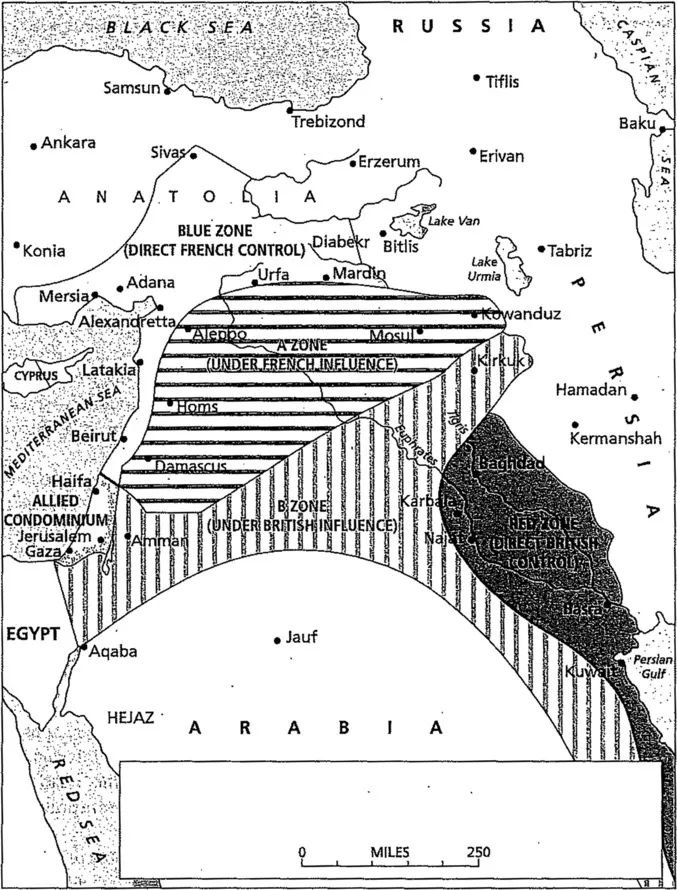

The League of Nations issued its mandates for Mesopotamia, Syria, and Palestine in April of 1920. The details of the British mandate were approved by the Council of the League of Nations in July 1922, and came into force on September 29, 1922. In the Mandate, the League of Nations recognized the “historical connection of the Jewish people with Palestine” and the “grounds for reconstituting their national home in that country.”

See reading #8, “The Mandate for Palestine (July 24, 1922)”

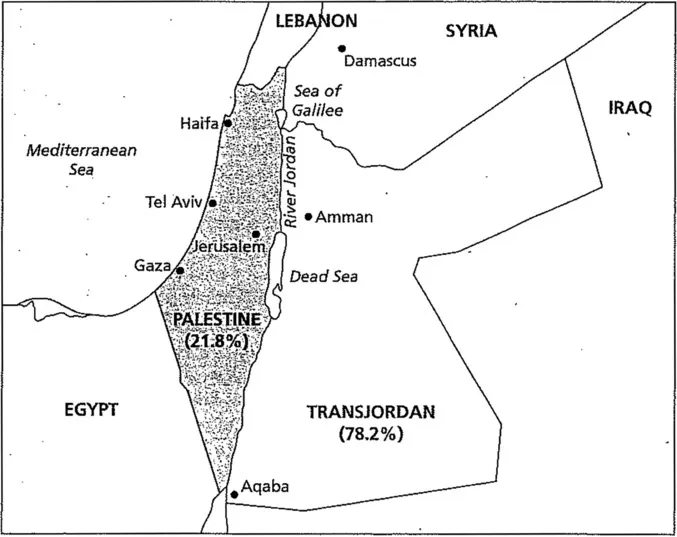

Map 3 The British Mandate, 1920.

Source: Republished with permission of Wadsworth, a division of Cengage Learning from ‘Israel: government and politics in a maturing state’, Gregory Mahler, 1989; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Another British White Paper was issued in October of 1930 in response to Arab riots in Palestine. The document, known as the “Passfield White Paper,” called for a renewed attempt at establishing a Legislative Council in Palestine. The White Paper was more restrictive in its approach to the Zionist cause, and as a result the Zionist movement mounted a major campaign against the White Paper at the time. In a letter made public during February 1931, British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald promised Chaim Weizmann what amounted to the cancellation of that White Paper.

See reading #9, “British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald Letter to Chaim Weizmann (February 13, 1931)”

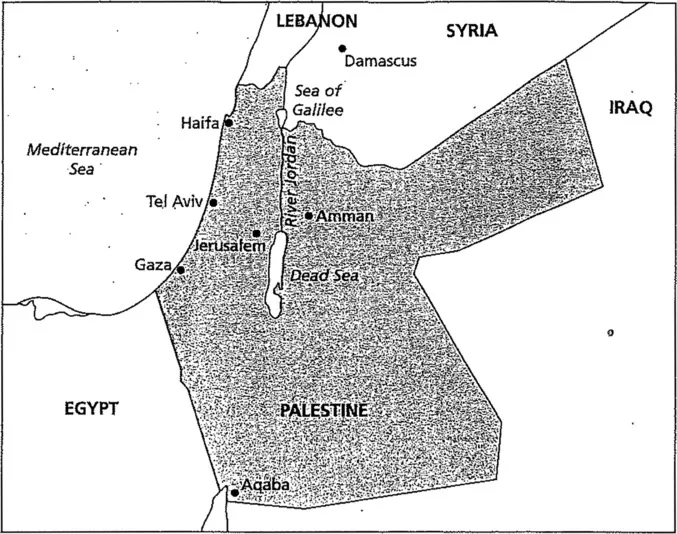

Map 4 The British Mandate, 1922.

Source: Republished with permission of Wadsworth, a division of Cengage Learning from ‘Israel: government and politics in a maturing state’, Gregory Mahler, 1989; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

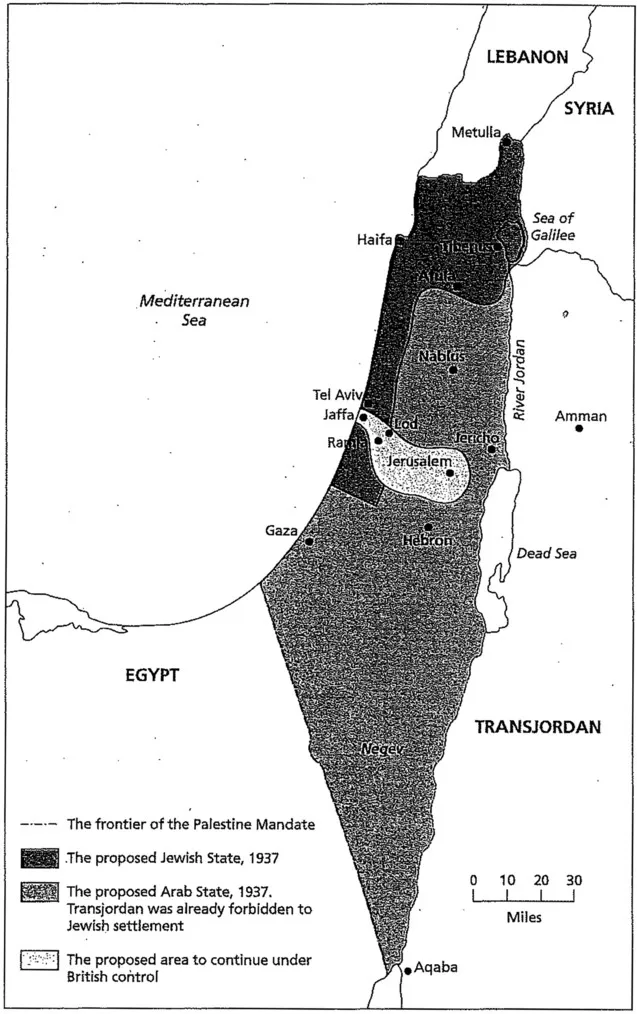

In November of 1936 a royal commission of inquiry known as the Peel Commission (after its chairman, William Robert Wellesley Peel, Earl of Peel) was sent on a fact-finding mission to Palestine by the British government in the hope that it might be able to recommend solutions to the tensions that were developing between the native Arab population and the immigrant Jewish population. It issued a report in July of 1937. The Peel Report found that many of the grievances of the Palestinians were reasonable and that the “disturbances” between the two populations were based on the issues of the Arab desire for national independence on one hand and a conflict between Arab nationalism and Zionist goals on the other. Ultimately the Peel Commission recommended partition of the Palestinian territory.

See reading #10, “The Palestine Royal Commission (Peel Commission) Report (July 24, 1937)”

Map 5 The Peel Commission Partition Proposal.

Source: Republished with permission of Wadsworth, a division of Cengage Learning from ‘Israel: government and politics in a maturing state’, Gregory Mahler, 1989; permission conveyed through Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

Although in 1937 the Twentieth Zionist Congress had rejected the boundaries proposed by the Peel Commission, it did agree in principle to the idea of partition of Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state. However, Palestinian Arab nationalists rejected any kind of partition. The British government sent a technical team in 1938, the Woodhead Commission, to make a detailed plan and to review the suggestions of the Peel Commission. The Woodhead Commission was in Palestine from April through August of 1938, and issued its report in November of that year. In its report it rejected the Peel plan and suggested other variations on the idea of partition. Ultimately the Woodhead Commission was unable to reach a single conclusion about how to partition Palestine in a way that would be acceptable to all concerned. As a consequence of that report the British Government took the position that it found the idea of partition as impractica...