Most of this book is about career choices in primary care and how to make the most of those opportunities. However, before we look at the jobs, this short chapter is about you, and what might suit you. We all have different backgrounds and circumstances, which affect the way we are able or want to work, and we all need to think about how to balance our work with the rest of our lives. For some, heavy financial commitments may mean that having a high income is paramount, whereas for others, family, illness and other interests may mean that shorter hours are important. There are no rules about what is right for you, only a whole set of choices to make – read on.

Welfare, workload and wad, the eternal triangle

Being happy with your job usually boils down to how you balance your workload and quality of patient care with the need to earn money and to remain healthy yourself. There is a common mind set in medicine which says that there is a difference between doctors and patients, and that doctors must always do everything they can for their patients, in an altruistic form of self-giving, and finally that it is not done to talk about money. So let me set the record straight.

Welfare

All of us at some point in our lives are patients. Whether we need simple contraception, help with an emergency, or help in dealing with long-term and life-threatening illness, ill health is part of what it is to be human, and so it will happen to you. Unfortunately many of us don’t manage this very well. We self-medicate, deny our problems, ignore common referral pathways in favour of a 30-second chat with a mate in the corridor, and sometimes literally work till we drop. I suffer from a recurrent depressive disorder and have done all these and more. Even when we realise we have problems it is not that easy. It is hard for the doctor who has a doctor as a patient to deal with internal thoughts such as ‘Am I doing this right?’, ‘What are they thinking of me?’ (as if this were a clinical exam), and perhaps the most difficult, ‘If she can be ill like this, it could really happen to me’. It is hard for the doctor patient too, often feeling a loss of power and vulnerable, and yet wanting to do things ‘right’. She may alter her presentation of the illness ‘to make it clearer for their colleague’ and prepackage symptoms into classic syndromes. She may hide personal bits or just ignore important details. Finally, accessing appropriate treatment can be a nightmare. This is all material for another book, but there are two important points to make in relation to career choices.

Firstly, make sure you take out income protection insurance to an adequate degree when you are young, fit and think you do not need it. Too many colleagues have ignored this advice, have later become ill and then of course found themselves uninsurable and therefore, if ill again, may have no income at all. Of all the advice in this book I would count this as the most important.

Secondly, we need as a profession to develop a culture that recognises our humanity, and that means building flexibilities into jobs to support each other. In The Project Surgery in East London we have deliberately set out to do this.

We are a small team of seven, working in small premises, and do not intend to expand. This is the sort of group size that can function supportively (consider the size of a well-functioning Balint group – about eight).

We spend time together over lunch, with the whole team, and in the evenings about once every month, being ordinary people together.

We try to manage working hours around childcare and healthcare parameters. For example, my work is fitted around psychotherapy sessions.

Being able to be supportive to team members is written into person specifications.

One partner brings her baby and au pair into the surgery so she can feel more comfortable because her baby is close by.

We have a £20k contingency fund, built out of profits. This is to be used, for example, to cover locum costs if one partner needs rapid admission for healthcare.

The point of all this is that we are potentially vulnerable and the harder your workload, the higher your risk. Take care with how you structure your work and for many this will mean reducing income and also compromising somewhat on the desire to be the perfect general practitioner (GP). ‘Good enough’ is good enough. Think carefully about part-time work and flexibilities in working. Thankfully, the idea that you can work all day, all night and the next day and be okay is beginning to slip away from most areas of primary care. However, it will probably be some time before a culture of full support such as we are developing at The Project Surgery becomes commonplace.

Patient care

Patient care is clearly at the heart of what we do, and no one sets out to be Dr Dreadful. However, getting it right all the time is not possible. So, we have clinical governance frameworks that try to help us to get better most of the time, and this brings with it the extra workload of measuring stuff, learning more stuff and pushing ourselves to do better. At the extreme we find GPs happy to visit on request, do childhood immunisations at home and, even in this age of opt-outs and well-developed co-operatives, do all their own on-calls themselves. I am sure their patients love them, but this does bring a very heavy workload and this will have an impact on health and well-being. You might on the other hand consider the concept of being the good enough’ GP to paraphrase Donald Winnicott’s concept describing the equilibrium new parents hopefully reach after the fantasy of being the perfect parent, and the bad parent, both of which give rise to distress in parents.1 GPs do not have to be perfect and can reasonably prioritise the more important aspects of care and put other stuff on the back burner without ‘failing’ their patients.

Money

Money is also important and it is generally true to say that in broad terms more work and more money tend to go together (although this does not explain why inner city GPs tend to earn less than leafy suburban GPs). There are issues about what money means to you in terms of self-image and perceived status. For some, and this is not really unreasonable, having a Mercedes is an important mark of having ‘made it’. Unfortunately, they do not come cheap and this may involve working harder to achieve it. On the other hand, even the humblest lifestyle requires funding, and there are issues like housing, which have an influence on how much you need to earn. In London, for example, if a GP aspired to the same lifestyle as me, with a four-bedroom house in London, a Skoda car and not much else extravagant, they would need to earn about £20k per year more than me, just to cover the extra interest payments on the house because I bought it at the depth of the 1980s housing crash, and it has tripled in value since. So, think carefully about money. The problem with looking to increase income is that it will probably mean more work, which may affect your sanity, and more work may also mean cutting back on the quality of patient care.

The balance

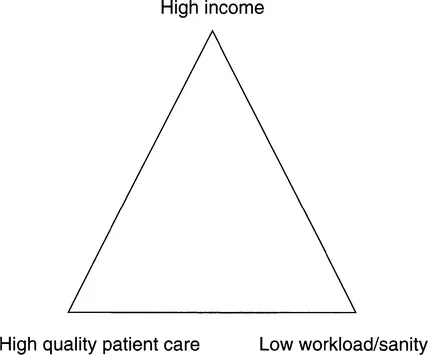

The basic issue then for all doctors is to balance high quality patient care with income and your own sanity (Figure 1.1). If this seems to be overdramatic, consider what happens if people get the balance wrong. Too many partnerships break up over the issue of perceived workload – ‘He doesn’t actually give the clinical workload the same degree of priority that I do’. Feeling that patient care is being compromised in a bid to earn more money causes tension and partnership breakdown, and finally we hear with sad regularity of GPs ending their own lives because of perceived stress of the job.

The balance is set something like this. Generally the higher the list size the greater the income, but also the higher the list size the greater the workload; the higher the workload the greater the pressure to restrict patient care. Your personal position on these axes is more important than negotiating particular workloads. The workaholic will always overdo their work time, whatever is agreed, and the bone idle will always tend to dodge their responsibilities. However, a partnership of relaxed people in touch with their social side may get on well, and a partnership of keen innovators dedicated to patient care may also work. Join the wrong sort of partnership though and it will be a disaster.

Figure 1.1 Workload is a balance between high income, quality patient care and one’s own sanity.

Example 1

Doctor A decided not to join the five-doctor practice. It was clear that his perfectionism set him a high workload, which he could tolerate. Probably in any setting he would be a workaholic. The others had different priorities and values and set themselves different workloads. All would be successful doctors but they would not form a successful partnership.

Example 2

Doctor N joined his new practice realising that the workload would be high, although the financial rewards would also be high. He was used to a high workload, having worked for two years in a very busy obstetrics and gynaecology department before turning to general practice, and he enjoyed a challenge. He therefore coped well in his new practice.

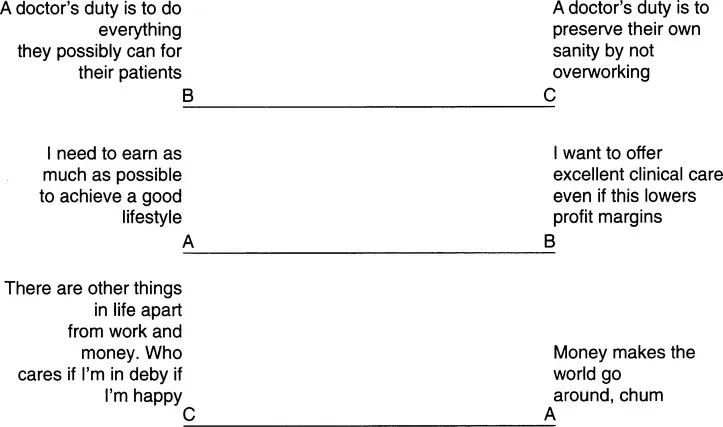

Figure 1.2 Balancing income, workload and the quality of care.

Doing the triangle

Look at Figure 1.2 opposite. These are known as non-judgemental value rating scales (NJVRS), first developed by Roger Neighbour in his book The Inner Apprentice2 Each consists of a linear analog scale (pompous word for a line’) set between two statements.

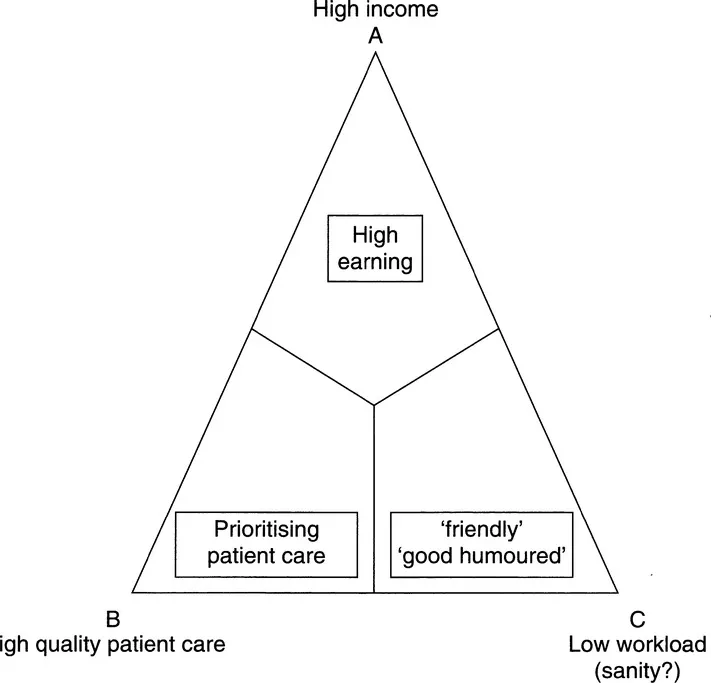

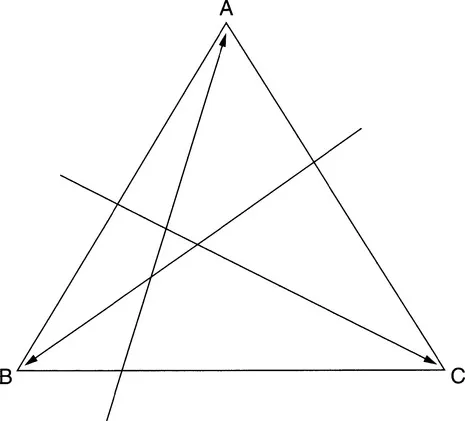

Figure 1.3 The workload triangle.

The statements are aimed to be the two ends of a spectrum of opinion, and you should mark off where you feel you would stand on each axis. You can then transfer your marks onto the sides of the workload triangle (Figure 1.3), being careful to keep each mark on the side in exactly the position as on the analog scale. So, if you marked near to A on the AB axis, you will make sure you transfer it to near A on the AB side. Finally if you draw a line from each mark, to the opposite corner of the triangle, you will make another small triangle, inside the larger one (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4 Example of a workload triangle.

Wher...