1 The nature of leadership

For centuries people have been fascinated by the topic of leadership, first in the realm of warfare and politics, and later in business and sports.1 Not that this interest has been constant, as attention has waxed and waned over the years, often depending on the great successes and historic tragedies brought about by highly visible leaders. Especially after the Second World War, the concept of leadership seems to have suffered by its connection to “Great Dictators,” such as Hitler, Mussolini and Stalin. To this day, the German word for leader, führer, is tainted by the memory of the slavish following of great evil. Unsurprisingly, few people take the phrase “Our Beloved Leader” to imply a compliment.

In business, too, an early interest in leadership gave way to a period of focus on technical management skills, such as finance, operations, marketing and strategy. Yet, during the last two decades, leadership has made a great comeback, in the thinking of business people, in the curricula of business schools and in the sales of books and Apps. Hordes of managers are sent off to leadership development programs, young people aspire to become “next generation leaders” and when things go wrong in companies, more often than not the media point to a lack of leadership as the root cause. It’s clear, leadership is hot.

But what is leadership? That depends on who you ask. So many people have jumped on the leadership bandwagon, adding their own hopes, fears, biases and twists, that we are at risk of losing sight of the fundamental nature of leadership. On the one hand, the concept of leadership has been stretched to encompass a curiosa shop of phenomena, making it seem to mean a lot of different things. On the other hand, most speakers and writers employ their own narrow notion of what they believe leadership should be, making it seem like something very specific. Interestingly, almost no one makes an effort to define leadership and to distinguish it from other concepts.

So, as it is the intention of this book to explore the qualities and pitfalls of various leadership styles, our journey must begin with a clarification of what we believe to be the essence of leadership. While it might seem a bit academic to start a book with definitions, having a focused and realistic image of what leadership is all about will serve us well, as we map different leadership styles and investigate how you might improve your own.

What leadership is not

Convictions are more dangerous enemies of truth than lies.

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (1844–1900) German academic and philosopher

As the word “leader” has collected so many layers of meaning over the years, coming to a clear understanding of the fundamental nature of leadership starts by stripping away the various coatings of varnish. So, with a nod to Michael Porter, who started his famous HBR article on What is Strategy2 by explaining what it is not, we can identify five different concepts with which leadership should not be confused. These are five common misconceptions about leadership that have contributed most to the muddled view so prevalent in practice and in theory.

Misconception 1: The leader as boss

Open a random annual report and most likely it will present “the top leadership team.” Ask a random HR manager to make a list of their business leaders and they will give you an org chart displaying all of their managers. Ask a random employee to name the leader of the organization and they will point to the highest-ranking manager. In all of these cases, the words leader and manager are used interchangeably. It has become increasingly fashionable to call managers leaders, probably because it sounds less technocratic, less 20th century. Just as someone with an MBA doesn’t want to be called a “business administrator” anymore, so too the label “manager” seems to have become dated, suggesting much less schwung than “leader,” prompting ever more people to migrate from the former label to the latter. Yet this is a confusing sort of inflation, mixing up a formal position with an informal authority. The two are fundamentally different.

To clarify the distinction between manager and leader, let us focus on the ultimate boss, the CEO, as example. Such a person undeniably fills a top management position, but does this automatically make the CEO a leader? Are people inclined to follow CEOs just because of the chair they are sitting in, or do CEOs need to bring more to the table to win people over and mobilize them to move in a certain direction? It is clear that CEOs can potentially command obedience using the formal powers of reward and punishment attached to their office. CEOs can appeal to their superior rank in the hierarchy and use “carrots” and “sticks” to get people to fall in line. In other words, being the boss gives CEOs the means to “buy” compliance. Under these circumstances, people will follow if it is in their economic interest to do so. In such a calculative relationship, people will do what the CEO demands if their return on investment of time and effort is high enough and/or if the potential punishment is too daunting. So, purely on the basis of their position, CEOs can get people to follow – call it followership via “wallets” and “whippings.”

However, almost all CEOs know that to get the best out of people requires more than bonuses and thumb screws. To get people truly on board requires the winning of hearts and minds. If people “have to” follow, their performance will be mediocre at best, but if they sincerely “want to,” their performance can be stellar. If CEOs can tap into people’s beliefs, passions, hopes and dreams, they can trigger enormous drive to join the company’s journey and contribute whole-heartedly to the company’s efforts. If CEOs can connect with people’s intrinsic motivation, they can build engagement and a resilience to overcome odds. Being the formal boss is not what sways people, but it is the CEO’s ability to inspire, charm, challenge, support, cajole, convince and even seduce – all qualities that have little to do with their management position and have everything to do with what they as individuals bring to the relationship. Under such circumstances, people will follow, not because it is in their economic, but in their emotional interest to do so. But they will need to respect and have trust in such CEOs to genuinely embrace them as individuals to willingly follow. Call it followership via “connection” and “confidence.”

So, if we start with a simple definition of leadership as the ability to get people to follow, very little of this ability will be rooted in a person’s formal position, while most will be found in how a person builds relationships, confidence and authority with others. Having the job of manager can help to get people to follow, as there will often be implicit respect for hierarchy and a sensitivity for potential rewards and punishment. Yet, having a management position can also interfere with getting others to follow, as people might question a manager’s motives – after all, as the old saying goes, where you “sit” determines where you “stand.” Managers are often mistrusted because they are driven by their own agenda, their own performance measures and their own narrow worldview.

While individuals can be appointed manager, they need to be accepted as leader. To have the ability to sway, leaders need to step forward and seek the lead, while winning people’s trust and approval to be allowed to do so. Whether CEO or first line supervisor, the formal appointment as manager somewhere in the hierarchy by no means ensures that someone will be embraced as leader. Every person who wants to lead will have to earn it. Leadership is relational, not positional.

Vice versa, being accepted as leader by no means suggests that one needs to be, or needs to become, the boss. Even without formal power, a person can have enormous informal influence and be accepted as a leader. This influence can be rooted in such elements as a person’s expertise, charisma, warmth, experience or passion, and will have been built up over time.

In Table 1.1 a playful overview is given of the distinction between being a manager and being a leader. To be absolutely clear, the two do not constitute opposite categories, such as the dichotomy between hot and cold, but just differing concepts, such as the distinction between hot and red – two very different things that are easily muddled if you don’t watch out.

Table 1.1 Comparing management and leadership

| | The World of the Manager | The World of the Leader |

| What do you do? | I have a JOB with rights and responsibilities | I fulfill a ROLE with or without a formal position |

| How do you become one? | I am APPOINTED by higher level managers | I become ACCEPTED by others who wish to follow |

| Which means do you have? | I have FORMAL POWERS to assign, spend, reward and punish | I have INFORMAL AUTHORITY built on trust, ability, inspiration and persuasion |

| What is your approach? | I get people to COMPLY by using carrots and sticks | I get people’s COMMITMENT by winning hearts and minds |

| How do people respond? | We have CALCULATIVE relations asking what’s in it for me | We have SYMBIOTIC relations as both care about a common goal |

| What is the best result? | ACCEPTABLE performance based on extrinsic motivation | EXCELLENT performance based on intrinsic motivation |

| Rule of thumb conclusion? | MANAGE THINGS Make sure that they HAVE TO | LEAD PEOPLE Make sure that they WANT TO |

Unfortunately, the confusing mix up between the terms manager and leader has a number of regrettable consequences. First, it lures managers into a false conviction of what is required to become a successful leader, suggesting that an appointment and formal power will do the trick. Take the example of Stefan, a highly qualified engineer, who for years had the difficult task of being head of global quality assurance at a Swiss manufacturer of construction materials. Despite being one of the best engineers in his field and developing excellent corporate procedures, he was unable to get production managers at the various sites around the world to implement his quality assurance measures. For years, he pleaded with the CEO to give him formal authority to “knock some heads together” and push through the necessary measures. After a major quality issue at one of the US plants, the CEO caved in and gave Stefan the powers he sought. Now Stefan was the global leader, or at least that’s what he thought. But instead of listening more attentively to Stefan, the regional production managers kept dragging their feet and poor quality remained an issue. Stefan was bewildered. So, he gradually went from commanding to threatening, punishing and manipulating, while quality standards hardly budged. It was only after a personal crisis and a run in with the disillusioned CEO that Stefan realized that he had sought more formal power so he could force people to comply instead of winning them over. It just hadn’t occurred to him that his job as manager gave him formal powers he actually shouldn’t use, because that would rub people the wrong way. Becoming the boss had seduced him into becoming bossy. So, although it felt uncomfortably vulnerable to stop sending instruction emails, he got on a plane and went out to listen to people. He found that some colleagues needed help and reassurance, others needed to be convinced, while yet others needed to be challenged. And it took time – as he put it himself: “As with my wife, the courtship took a while, and even now I have to keep working on our relationship.” But the improvements were dramatic.

Besides finding out the hard way that leadership is about engagement instead of enforcement, Stefan also learnt about the second consequence of the manager–leader mix up – a misunderstanding of where leaders are to be found in an organization. While in Brazil, he discovered that the real leaders of quality improvement were not the highest-ranking managers, but some production experts in the factories, who were widely respected by employees. Stefan had been so fixated on the hierarchy, getting the plant managers to deploy his quality procedures, that he failed to see that the key opinion leaders whose backing he needed were lower level managers or not even managers at all. Once he had the acceptance of these leaders and they rallied people in the factories to implement upgraded procedures, the formal plant managers quickly offered their belated support. On the basis of this experience, Stefan went out to find the “real leaders” at all the plants, at whatever level they were. And where leadership was lacking, he encouraged passionate people to step up and take a leadership role in the quality assurance process, whatever their formal position.

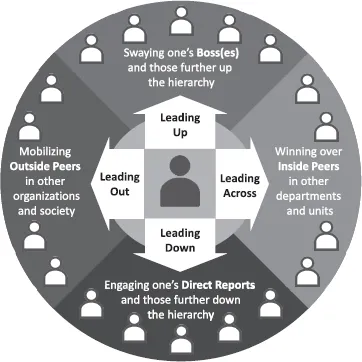

As the example of Stefan shows, it is easy to slip into this widespread misconception of equating leadership to management, but it is extremely unhelpful, masking what leaders really do and where they can be found. Leadership is the distinct quality of getting people to follow and leaders do this by using their built-up authority to sway people. As such, leadership can be exercised by anyone in (and outside) an organization at certain moments and on certain subjects. Employees can lead their bosses on some topics, while bosses can lead on others. Colleagues can lead each other, while they can also lead outside their organization, in coalitions or in the broader community. It is in this context that it can be said that we “manage downwards” but can “lead 360” (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Leading whom? Leadership circle of influen...