Introduction

Fifteen years ago, I was asked to evaluate a young deaf man with behavioral problems, labile emotions, and academic difficulties. Nothing in his educational, medical, or psychological testing history seemed to explain his presenting symptoms. He was superficially articulate, charming, and warm—yet his thinking was unusually concrete. He showed gaps in empathy with others and was prone to angrily acting out. Stymied, I speculated that rather than a mental illness, he had “some type of learning disability.”

I would now diagnose this patient with “language deprivation syndrome.” That is, even though he was educated in programs designed for deaf children, his brain was exposed to insufficient linguistic input in earliest childhood to foster the development of a truly fluent first language. Although he later learned a great deal more language, he continued to exhibit deficits in nearly every area of daily functioning, not merely in his language skills. These deficits persisted despite intensive (and expensive) remedial schooling and vocational support.

Perhaps once a century, a child with normal hearing experiences isolation from human contact so profound as to prevent learning a “mother tongue.” Among deaf children, by contrast, incomplete language acquisition is epidemic. Acquiring language—any language—is the greatest challenge that deaf children face. Yet the reality and the risks of language deprivation are barely noted in the scientific literature or among the hearing majority. As the example before shows, they are not even readily identified by supposed experts in deafness. Deaf children can be raised in loving homes, treated by medical specialists, fitted with high-tech electronic aids, and provided special education, yet still emerge from childhood with a devastating, permanent, and preventable disability.

Early language deprivation seems to cause a recognizable constellation of social, emotional, intellectual, and other consequences. I term this constellation Language Deprivation Syndrome (LDS) to emphasize its internal coherence and its predictability. This name has the advantage of placing responsibility for a child’s language and associated outcomes on the surrounding environment. Poor language outcomes, though frequently tolerated, are not “normal” for deaf people. It has the potential disadvantage, however, of exacerbating the pain and guilt that parents, educators, and medical professionals may feel when its seriousness in a particular child’s case becomes evident. Language deprivation is often the unintended outcome of well-intentioned efforts to promote a child’s language development. Caregivers’ intentions, however, cannot substitute for children’s actual outcomes. These have all too often been “swept under the rug” in educational and medical research.

Structurally speaking, LDS is incomplete neurodevelopment. Functionally, it is an intellectual disability. Because language mediates and underlies nearly every human activity, those seeking to understand LDS must explore concepts and research from a wide variety of fields. That no single authority takes responsibility for a child’s language development may be the main reason the syndrome persists. I delve into some far-flung areas in the following, but as a clinician primarily, I will base this chapter mainly on direct experience with the language-deprived deaf patients whom I have evaluated or treated in various settings. These include my primary work sites at Harvard Medical School, the Deaf & Hard of Hearing Service at Cambridge Hospital, and the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Program at Boston Children’s Hospital—as well as past experience at the Mental Health Unit for Deaf Persons at Westborough State Hospital (which was cofounded by this volume’s co-editor Neil S. Glickman) and the Deaf schools and programs where I have consulted. Naturally, I owe innumerable patients, their families, and perceptive colleagues for their stories and insights into these complex issues.

Although the phrase “language deprivation syndrome” may be new, the observation, that deficits observed in some deaf people’s life skills might be due not to sensory deprivation or to social impoverishment, but specifically to language deprivation, is not. Prior to the groundbreaking adoption of sign language into US public education in the nineteenth century, the New York Times described deaf people as existing “in a state of barbarism, unprovided with the most ordinary means of culture” (New York [Daily] Times, Sept 29, 1852). Decades of the successful use of American Sign Language (ASL), disseminated via state schools established nationwide, ended with the rise of “oralism.” This philosophy of prioritizing the teaching of speech and lip-reading while banning, and even punishing, the use of sign language led to wholesale language deprivation among deaf people in the twentieth century. “In looking back to the educational methods formerly used with the deaf,” said psychologist Edna Levine in 1968, “you would have seen each individual more or less encased in his own little glass tomb” (Rainer & Altshuler, 1968).

As the mental health disciplines emerged, pioneering practitioners published descriptions of LDS (See Altshuler, 1962; Glickman, 2009; Hall, Levin, & Anderson, 2017; Levine, 1956; Myklebust, 1960; Vernon & Raifman, 1997). The initial understanding was sometimes tinged with condescension based on two assumptions: that deafness must represent a “loss” to the individual and that signed languages must be inferior to spoken. Some early terminology would now be considered pejorative, e.g., surdophrenia or primitive personality disorder, but a serious effort was begun to describe the lives and experiences of deaf people. In New York, a perceptive observer reviewed three classic descriptions and commented:

These three sets of results—Myklebust, Altshuler, and Levine—are remarkably consistent. However, the problem of explanation remains: one still doesn’t know the etiology of the problems the deaf have. A phenomenological-descriptive model is just a beginning. The actual language of the deaf must be examined in more detail. …Just how much deprivation exists? At what point do the deaf fail conceptually, and how does this relate (if at all) to their emotional and social problems? Is sign language, which remains the most common means of communication amongst the American deaf, despite the efforts of all education for the deaf in the United States, a language, and does it have limitations? What part do experiential and language deprivation play in creating the condition of the deaf in the United States?

(Kohl, 1966)

Fifty years later, the answers to Kohl’s cogent questions have emerged with forceful clarity. The 1960s brought the recognition that sign languages are in fact the linguistic equals of spoken languages. The 1970s saw the rebirth of a confident Deaf culture whose members experience deafness as a valid and satisfying mode of human being. New research vividly demonstrates the brain’s time-sensitivity for acquiring language and begins to illuminate the neurological correlates of incomplete acquisition. We can now validate Kohl’s intuition that “the single greatest problem” deaf children face is in fact what he called “language disability” (Kohl, 1966).

In 1854, a merchant politely asked a customer to leave his store. When the customer ignored him, the owner tried to shove him out. The customer, who was deaf, later pled guilty to having stabbed the owner. In this unfortunate event, neither person seems fully responsible. A proprietor manhandled a recalcitrant customer. A deaf man defended himself in an unprovoked assault. A misunderstanding between deaf and hearing worlds seems at fault, a theme that can be traced continuously forward in Deaf history all the way to the current debate over “maladaptive cross-modal plasticity” that will be discussed as follows. In a bio-psycho-social-cultural model of mental health, such Deaf-hearing cultural issues loom large. They place a premium on the attitude with which we approach “deaf people’s problems” (Glickman, 2013). This chapter is written as this writer’s research and clinical work are undertaken: with respect for deaf people’s actual lived experiences, and therefore with skepticism toward the narrow view of deafness as mere pathology.

How Does Language Deprivation Happen?

The existence of language deprivation is a corollary to the existence of a critical period for learning one’s first language. The most severe cases of deprivation therefore follow a child’s not being exposed to consistent and fully elaborated language during the entire critical period, approximately the first five years of life.

Each child’s brain and linguistic history is unique; each case of language deprivation is therefore also unique. Broadly speaking, congenitally deaf children are at greatest risk for deprivation while children who become deaf during the critical period are partly protected (examples of the latter include Helen Keller and the strident oral advocate David Wright). Children likely vary in the strength of their “language instinct” (Pinker, 1994)—their inbuilt avidity for language—and the rate and manner in which their critical periods close.

Geography is sometimes decisive: a child born deaf into a remote village may lack for both hearing aids and a local sign language. Such a child may grow up loved and well cared for but without linguistic communication. The ASL interpreter and activist Susan Schaller provided a moving account of one such case in her book, “A Man Without Words” (Schaller, 2012), documenting her passionate efforts to remediate the language deprivation of a man from rural Mexico. Although in countries where the education of deaf children is mandated, language deprivation as profound as that which Schaller describes is rarely seen clinically, this does not mean it is rare.

The same factors that impede language acquisition in the first place—geographic isolation, lack of educational opportunities and social services, lack of appreciation that the child (or now, adult) has specialized needs—can result in a language-deprived person’s remaining home with family, living homeless, being wrongly placed in an institution for intellectual disability (see Miller, 2016), or being jailed, all without recognition of the person’s specific deficits and needs. Such cases can come to light when a legal, medical, or behavioral problem appears or after a long-term support disappears.

Following profound deprivation, the amount of language that can be acquired, even after intensive exposure, is variable. In this regard, Schaller’s case was close to the median: “Ildefonso,” as she called him, acquired valuable ability to communicate, allowing him to better navigate the world. He did not achieve fluent language. Many such people acquire little language no matter how intense the exposure.

The author has observed only one case of the late acquisition of nearly fluent language. This case is presented with the individual’s permission here:

Iromilson, known as “Ro,” was born deaf on an island with no indigenous sign language and few services for deaf people. He roamed freely on his bicycle, rarely attending school. He particularly enjoyed the harbor, where he watched fishing boats being built. He communicated via pantomime and “home signing.” Home signs are idiosyncratic gestures that arise naturally in each deaf person’s environment. Presumably they arise from the brain’s “language instinct” (Pinker, 1994) expressing itself in the absence of an actual language to acquire. Unfortunately, even the richest home sign, such as that developed by language-deprived deaf siblings, has never been found to reach the full grammatical power of true language.

Ro’s single mother moved her family to the United States in search of education for her son. He wandered Boston at all hours, “stole” a cell phone, and found himself psychiatrically hospitalized. There he vividly gestured the story of his good luck in finding a phone. After failed attempts in local schooling, he was placed in a residential, therapeutic Deaf school.

Ro, now 14, was at first unable to sit still in a classroom, but he had not entirely lost every young child’s intense hunger for language and near-magical capacity to absorb its grammatical “machinery.” His school was largely staffed, day and night, by fluently signing Deaf people. Over six years of intensive exposure, Ro acquired remarkably fluent ASL. He also mastered some spoken and written English.

Ro still rides his bicycle joyfully but can also engage in team sports. He has friends, and a girlfriend. He has learned a range of carpentry skills and expects to be fully employed. He admires his mother and feels grateful for the sacrifices she made on his behalf—nuanced, empathic thoughts of a type often absent in LDS. He does struggle with residual deficits in world knowledge and associated judgments and would be the first to admit that he can lack common sense. Unfortunately, his success story is vanishingly rare.

Characteristics of Deaf People with Language Deprivation Syndrome

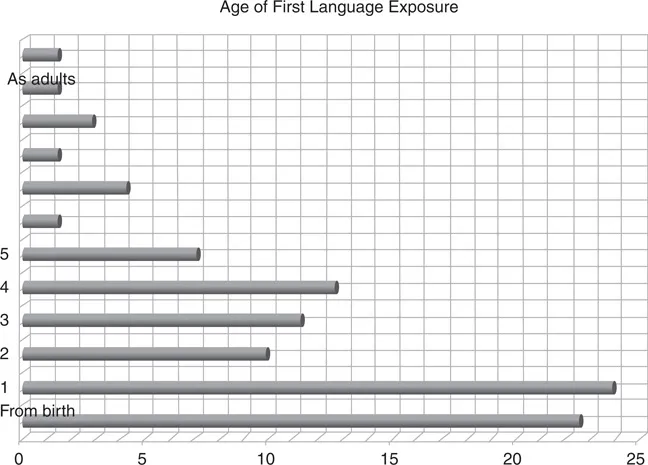

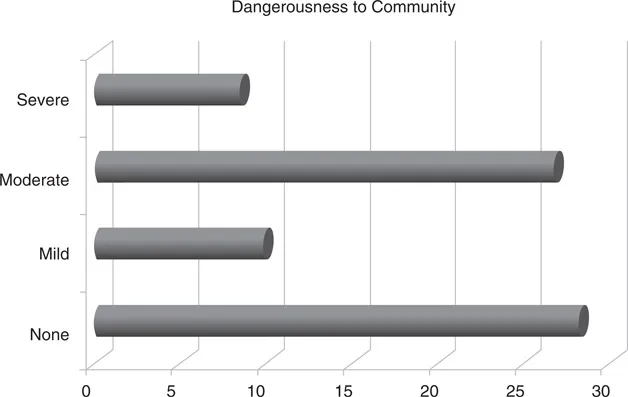

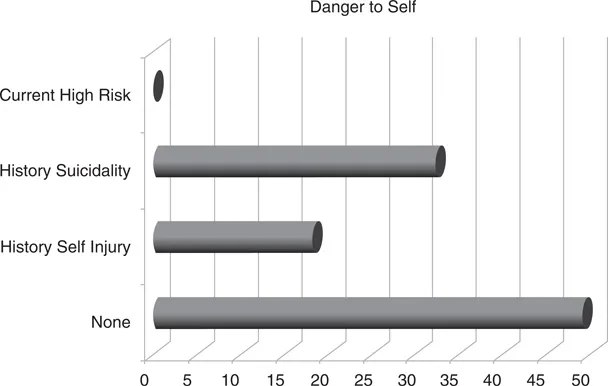

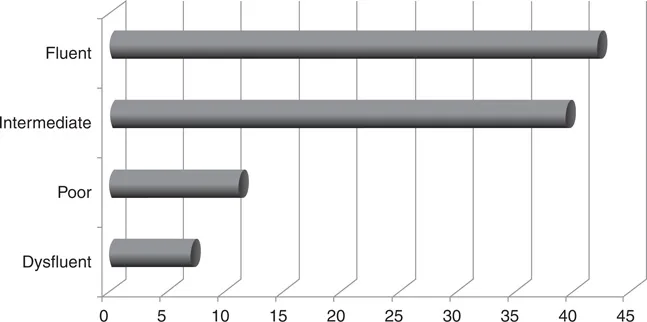

In 1999, the author examined a series of 98 consecutive referrals to the Deaf Service at Cambridge Hospital. Each case was rated for severity of behavioral symptoms and for language fluency. The initial hypothesis was that being unable to solve social and emotional problems with words would lead to “acting out” emotions behaviorally. Despite the coarseness of the categorizations (chosen to ensure high interrater reliability), surprisingly significant correlations emerged: both dangerousness to oneself and dangerousness to others correlated strongly with language dysfluency.1 Indeed, nearly half of the variance in these deaf psychiatric patients’ aggressive behaviors seemed attributable to problems with language. Figures 1.1–1.4 describe this dataset.2

Note that fewer than half of the patients in this sample demonstrated fluency in American Sign Language. In hindsight, with heightened awareness of the serious consequences of even mild language deficits, the language categories might more accurately be named mild, moderate, and severely dysfluent.

Following the aforementioned pilot work, the author compiled a list of potential descriptors for LDS from published reports and active professionals in the field. The incidence of 53 potential descriptors was then noted in the sample described earlier. The ten outstanding categories of LDS characteristics, presented as follows, paint a picture of LDS as seen in the mental health clinic. Because data collection and analysis on an ever-expanding sample continue at the time of this writing, the findings here are preliminary. The discriminatory power of individual items relative to other psychiatric diagnoses remains to be determined, as do their independence from one another and prevalence at different degrees of language deprivation.

A Person with LDS May Superficially Appear to Use Sign Language Fluently, But on Closer Examination, Shows Characteristic Linguistic Deficits

Nearly every deaf person who experiences significant language deprivation eventually finds his or her way to some form of sign language, even if educated orally (Gregory, Bishop, & Sheldon, 1995). Late-deafened native users of spoken language, particularly the elderly, are much less likely to seek out sign language, as are mildly and moderately hard of hearing people, who face their own difficulties with social communication but rarely suffer from language deprivation.

To non-signers, the sign language of a person with LDS may be indistinguishable from that of a fluent signer; handshapes and movements can appear natural and impressively fast. Fluent signers (particularly native signers), however, recognize the absence of features and functions of full language, and the more general cognitive and emotional “gestalt” of a person who has experienced language deprivation. In the mo...