![]()

Part I: In Search of a Framework

![]()

1. Assumptions about the Nature of Social Science

Central to our thesis is the idea that 'all theories of organisation are based upon a philosophy of science and a theory of society'. In this chapter we wish to address ourselves to the first aspect of this thesis and to examine some of the philosophical assumptions which underwrite different approaches to social science. We shall argue that it is convenient to conceptualise social science in terms of four sets of assumptions related to ontology, epistemology, human nature and methodology.

All social scientists approach their subject via explicit or implicit assumptions about the nature of the social world and the way in which it may be investigated. First, there are assumptions of an ontological nature - assumptions which concern the very essence of the phenomena under investigation. Social scientists, for example, are faced with a basic ontological question: whether the 'reality' to be investigated is external to the individual - imposing itself on individual consciousness from without - or the product of individual consciousness; whether 'reality' is of an 'objective' nature, or the product of individual cognition; whether 'reality' is a given 'out there' in the world, or the product of one's mind.

Associated with this ontological issue, is a second set of assumptions of an epistemological nature. These are assumptions about the grounds of knowledge - about how one might begin to understand the world and communicate this as knowledge to fellow human beings. These assumptions entail ideas, for example, about what forms of knowledge can be obtained, and how one can sort out what is to be regarded as 'true' from what is to be regarded as 'false'. Indeed, this dichotomy of 'true' and 'false' itself pre-supposes a certain epistemological stance. It is predicated upon a view of the nature of knowledge itself: whether, for example, it is possible to identify and communicate the nature of knowledge as being hard, real and capable of being transmitted in tangible form, or whether 'knowledge' is of a softer, more subjective, spiritual or even transcendental kind, based on experience and insight of a unique and essentially personal nature. The epistemological assumptions in these instances determine extreme positions on the issue of whether knowledge is something which can be acquired on the one hand, or is something which has to be personally experienced on the other.

Associated with the ontological and epistemological issues, but conceptually separate from them, is a third set of assumptions concerning human nature and, in particular, the relationship between human beings and their environment, All social science, clearly, must be predicated upon this type of assumption, since human life is essentially the subject and object of enquiry. Thus, we can identify perspectives in social science which entail a view of human beings responding in a mechanistic or even deterministic fashion to the situations encountered in their external world. This view tends to be one in which human beings and their experiences are regarded as products of the environment; one in which humans are conditioned by their external circumstances. This extreme perspective can be contrasted with one which attributes to human beings a much more creative role; with a perspective where 'free will' occupies the centre of the stage; where man is regarded as the creator of his environment, the controller as opposed to the controlled, the master rather than the marionette. In these two extreme views of the relationship between human beings and their environment we are identifying a great philosophical debate between the advocates of determinism on the one hand and voluntarism on the other. Whilst there are social theories which adhere to each of these extremes, as we shall see, the assumptions of many social scientists are pitched somewhere in the range between.

The three sets of assumptions outlined above have direct implications of a methodological nature. Each one has important consequences for the way in which one attempts to investigate and obtain 'knowledge' about the social world. Different ontologies, epistemologies and models of human nature are likely to incline social scientists towards different methodologies. The possible range of choice is indeed so large that what is regarded as science by the traditional 'natural scientist' covers but a small range of options. It is possible, for example, to identify methodologies employed in social science research which treat the social world like the natural world, as being hard, real and external to the individual, and others which view it as being of a much softer, personal and more subjective quality.

If one subscribes to a view of the former kind, which treats the social world as if it were a hard, external, objective reality, then the scientific endeavour is likely to focus upon an analysis of relationships and regularities between the various elements which it comprises. The concern, therefore, is with the identification and definition of these elements and with the discovery of ways in which these relationships can be expressed. The methodological issues of importance are thus the concepts themselves, their measurement and the identification of underlying themes. This perspective expresses itself most forcefully in a search for universal laws which explain and govern the reality which is being observed.

If one subscribes to the alternative view of social reality, which stresses the importance of the subjective experience of individuals in the creation of the social world, then the search for understanding focuses upon different issues and approaches them in different ways. The principal concern is with an understanding of the way in which the individual creates, modifies and interprets the world in which he or she finds himself. The emphasis in extreme cases tends to be placed upon the explanation and understanding of what is unique and particular to the individual rather than of what is general and universal. This approach questions whether there exists an external reality worthy of study. In methodological terms it is an approach which emphasises the relativistic nature of the social world to such an extent that it may be perceived as 'anti-scientific' by reference to the ground rules commonly applied in the natural sciences.

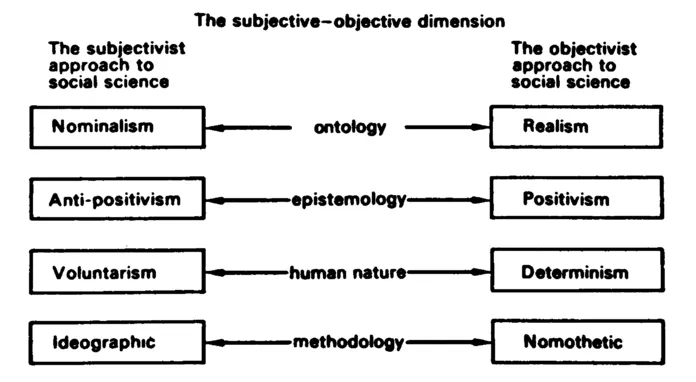

Figure 1.1 A scheme for analysing assumptions about the nature of social science

In this brief sketch of various ontological, epistemological, human and methodological standpoints which characterise approaches to social sciences, we have sought to illustrate two broad and somewhat polarised perspectives. Figure 1.1 seeks to depict these in a more rigorous fashion in terms of what we shall describe as the subjective—objective dimension. It identifies the four sets of assumptions relevant to our understanding of social science, characterising each by the descriptive labels under which they have been debated in the literature on social philosophy. In the following section of this chapter we will review each of the four debates in necessarily brief but more systematic terms.

The Strands of Debate

Nominalism—realism: the ontological debate1

These terms have been the subject of much discussion in the literature and there are great areas of controversy surrounding them. The nominalist position revolves around the assumption that the social world external to individual cognition is made up of nothing more than names, concepts and labels which are used to structure reality. The nominalist does not admit to there being any 'real' structure to the world which these concepts are used to describe. The 'names' used are regarded as artificial creations whose utility is based upon their convenience as tools for describing, making sense of and negotiating the external world. Nominalism is often equated with conventionalism, and we will make no distinction between them.2

Realism, on the other hand, postulates that the social world external to individual cognition is a real world made up of hard, tangible and relatively immutable structures. Whether or not we label and perceive these structures, the realists maintain, they still exist as empirical entities. We may not even be aware of the existence of certain crucial structures and therefore have no 'names' or concepts to articulate them. For the realist, the social world exists independently of an individual's appreciation of it. The individual is seen as being born into and living within a social world which has a reality of its own. It is not something which the individual creates—it exists 'out there'; ontologically it is prior to the existence and consciousness of any single human being. For the realist, the social world has an existence which is as hard and concrete as the natural world.3

Anti-positivism—positivism: the epistemological debate4

It has been maintained that 'the word "positivist" like the word "bourgeois" has become more of a derogatory epithet than a useful descriptive concept'.5 We intend to use it here in the latter sense, as a descriptive concept which can be used to characterise a particular type of epistemology. Most of the descriptions of positivism in current usage refer to one or more of the ontological, epistemological and methodological dimensions of our scheme for analysing assumptions with regard to social science. It is also sometimes mistakenly equated with empiricism. Such conflations cloud basic issues and contribute to the use of the term in a derogatory sense.

We use 'positivist' here to characterise epistemologies which seek to explain and predict what happens in the social world by searching for regularities and causal relationships between its constituent elements. Positivist epistemology is in essence based upon the traditional approaches which dominate the natural sciences. Positivists may differ in terms of detailed approach. Some would claim, for example, that hypothesised regularities can be verified by an adequate experimental research programme. Others would maintain that hypotheses can only be falsified and never demonstrated to be 'true'.6 However, both 'verificationists' and 'falsificationists' would accept that the growth of knowledge is essentially a cumulative process in which new insights are added to the existing stock of knowledge and false hypotheses eliminated.

The epistemology of anti-positivism may take various forms but is firmly set against the utility of a search for laws or underlying regularities in the world of social affairs. For the anti-positivist, the social world is essentially relativistic and can only be understood from the point of view of the individuals who are directly involved in the activities which are to be studied. Anti-positivists reject the standpoint of the 'observer', which characterises positivist epistemology, as a valid vantage point for understanding human activities. They maintain that one can only 'understand' by occupying the frame of reference of the participant in action. One has to understand from the inside rather than the outside. From this point of view social science is seen as being essentially a subjective rather than an objective enterprise. Anti-positivists tend to reject the notion that science can generate objective knowledge of any kind.7

Voluntarism—determinism: the 'human nature' debate

This debate revolves around the issue of what model of man is reflected in any given social-scientific theory. At one extreme we can identify a determinist view which regards man and his activities as being completely determined by the situation or 'environment' in which he is located. At another extreme we can identify the voluntarist view that man is completely autonomous and free-willed. Insofar as social science theories are concerned to understand human activities, they must incline implicitly or explicitly to one or other of these points of view, or adopt an intermediate standpoint which allows for the influence of both situational and voluntary factors in accounting for the activities of human beings. Such assumptions are essential elements in social-scientific theories, since they define in broad terms the nature of the relationships between man and the society in which he lives.8

Ideographic—nomothetic theory: the methodological debate

The ideographic approach to social science is based on the view that one can only understand the social world by obtaining first-hand knowledge of the subject under investigation. It thus places considerable stress upon getting close to one's subject and exploring its detailed background and life history. The ideographic approach emphasises the analysis of the subjective accounts which one generates by 'getting inside' situations and involving oneself in the everyday flow of life - the detailed analysis of the insights generated by such encounters with one's subject and the insights revealed in impressionistic accounts found in diaries, biographies and journalistic records. The ideographic method stresses the importance of letting one's subject unfold its nature and characteristics during the process of investigation.9

The nomothetic approach to social science lays emphasis on the importance of basing research upon systematic protocol and technique. It is epitomised in the approach and methods employed in the natural sciences, which focus upon the process of testing hypotheses in accordance with the canons of scientific rigour. It is preoccupied with the construction of scientific tests and the use of quantitative techniques for the analysis of data. Surveys, questionnaires, personality tests and standardised research instruments of all kinds are prominent among the tools which comprise nomothetic methodology.10

Analysing Assumptions about the Nature of Social Science

These four sets of assumptions with regard to the nature of social science provide an extremely powerful tool for the analysis of social theory. In much of the literature there is a tendency to conflate the issues which are in...