![]()

1

Geospatial Data Science: A Transdisciplinary Approach

Emre Eftelioglu, Reem Y. Ali, Xun Tang, Yiqun Xie, Yan Li, and Shashi Shekhar

Contents

1.1Introduction

1.1.1Motivation

1.1.2Problem Definition

1.1.3Challenges

1.1.4Trade-Offs

1.1.5Background

1.1.6Contributions and the Scope and Outline of This Chapter

1.2Statistics

1.2.1Traditional Statistics

1.2.2Traditional Statistics versus Spatial Statistics

1.2.3Spatial Statistics

1.3Mathematics

1.3.1Mathematics in Traditional Data Science

1.3.2Limitations of Applying Traditional Mathematical Models to Spatial Data and Novel Spatial Models via Examples

1.4Computer Science

1.4.1Core Questions and Goals

1.4.2Concepts, Theories, Models, and Technologies

1.4.3Limitations of Traditional Data Science for Spatial Data and Related Computer Science Accomplishments

1.5Conclusion

References

1.1Introduction

This chapter provides a transdisciplinary scientific perspective for the geospatial data science which promises to create new frontiers for the geospatial problems which were previously studied with a trial and error approach. A well-known example from the past illustrates how rigorous scientific methods may change a field. Alchemy, the medieval forerunner of chemistry, once aimed to transform matter into gold (Newman and Principe 1998). Alchemists worked tirelessly for years trying to combine different matter and observe their effects. This trial and error process was successful for finding new alloys (e.g., brass, bronze, etc.) but not for creating another metal, that is, gold. Later, the science of chemistry showed the chemical reactions and their effects on elements, and successfully proved that an element cannot be created by simply melting and combining other elements.

We see similar unrewarded efforts (Legendre et al. 2004; Mazzocchi 2015) in the current trial and error approach to geospatial data science. We believe that research in the field needs to be conducted more systematically using methods scientifically appropriate for the data at hand.

This chapter investigates geospatial data science from a transdisciplinary perspective to provide such a systematic approach with the collaboration of scientific disciplines, namely, mathematics, statistics, and computer science.

1.1.1Motivation

Over the past decade, there has been a significant growth of cheap raw geospatial data in the form of GPS trajectories, activity/event locations, temporally detailed road networks, satellite imagery, etc. (H. J. Miller and Han 2009; Shekhar et al. 2011). These data, which are often collected around the clock from location-aware applications, sensor technologies, etc., represent an unprecedented opportunity to study our economic, social, and natural systems and their interactions.

Consequently, there has also been rapid growth in geospatial data science applications. Often, geospatial information retrieval tools have been used as a type of “black box,” where different approaches are tried to find the best solution with little or no consideration of the actual phenomena being investigated. Such approaches can have unintended economic and social consequences. An example from computer science was Google’s “Flu Trends” service, begun in 2008, which claimed to forecast the flu based on people’s searches. The idea was that when people have flu, they search for flu-related information (e.g., remedies, symptoms). Google claimed to be able to track flu trends earlier than the Centers for Disease Control. However, in 2013, the approach failed to identify the flu season, missing the peak time by a large margin (e.g., 140%) (Butler 2013; Lazer et al. 2014; Drineas and Huo 2016).

This failure is but one example of how the availability of a computational tool does not mean that the tool is suitable for every problem. A recent New York Times article discussed similar issues in big data analysis from the statistics perspective, concluding, “[Statistics is] an important resource for anyone analyzing data, not a silver bullet.” (Marcus and Davis 2014).

Similarly, geospatial data science applications need a strong foundation to understand scientific issues (e.g., generalizability, reproducibility, computability, and prediction limits—error bounds), which often makes it difficult for users to develop reliable and trustworthy models and tools. Moreover, we need a transdisciplinary scientific approach that considers not only one scientific domain but multiple scientific domains for discovering and extracting interesting patterns in them to understand past and present phenomena and provide dynamic and actionable insights for all sectors of society (Karimi 2014).

1.1.2Problem Definition

The term geospatial data science implies the process of gaining information from geospatial data using a systematic scientific approach that is organized in the form of testable scientific explanations (e.g., proofs and theories, simulations, experiments, etc.). A good example is USGS and NOAA’s analysis of geospatial and spatiotemporal datasets, for example, satellite imagery, atmospheric data sensors, weather models, and so on, to provide actionable hurricane forecasts using statistics, machine learning (computer science), and mathematical models (Graumann et al. 2005; “National Hurricane Center” 2017).

The most important aspect of a scientific process is objectivity (Daston and Galison 2007), meaning the results should not be affected by people’s perspectives, interests, or biases. To achieve objectivity, scientific results should be reproducible (Drummond 2009; Peng 2011). In other words, using the claims in a scientific study, the results should be consistent and thus give the same results every time.

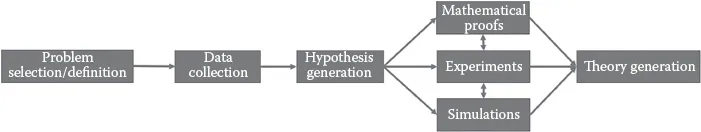

Although they vary by domain (Gauch 2003), for geospatial data science we provide the following steps (Figure 1.1), which can provide objectivity and reproducibility.

Figure 1.1

Steps of geospatial data science.

The first step is the selection of a phenomenon to explain scientifically. In other words, we decide which problem we want to explain. Next, sufficient data about the phenomenon are collected to generate a hypothesis. The important aspect of this step is that hypothesis generation should be objective and not biased by scientists’ perspective or interests. Experiments and simulations are then done to test the hypothesis. If the hypothesis survives these tests, then a theory can be generated. Note that in some domains, theories can be validated by mathematical proofs, and then confirmed by experiments and simulations. Thus, scientific methods differ slightly from one scientific domain to another.

This scientific process will also draw boundaries of predictability just as chemistry drew boundaries for creating matter (i.e., gold). Depending on the data in hand, non-stationarity in time may impact the success of predictability. Thus, past events may not always help predict the future. Similarly, black swan events, where the occurrence of a current event deviates from what is expected, may escape the notice of individual disciplines (Taleb 2007). The proposed transdisciplinary approach encourages us to investigate such events for better understanding the cause and predictability of black swan events with a scientific approach.

1.1.3Challenges

Geospatial data science poses several significant challenges to both current data scientific approaches as well as individual scientific disciplines.

First, the increasing size, variety, and the update rate of geospatial data exceed the capacity of commonly used data science approaches to learn, manage, and process them with reasonable effort (Evans et al. 2014; Shekhar, Feiner, and Aref 2015). For example, vehicle trajectory datasets that are openly published on the Planet GPX web site include trillions of GPS points, each of which carries longitude, latitude, and time information (“Planet.gpx—OpenStreetMap Wiki” 2017).

Second, geospatial data often violate fundamental assumptions of...