Since its publication by Pearson and Gallagher (1983a, 1983b) the GRR Model has been a significant and influential model in the literacy field (Pearson, 2013). It has demonstrated remarkable staying power, and if anything, only increased in use and application. An Ngram graph (See Figure 1.1) provides a visual of the increasing frequency of the term from 1983 to 2008 (the last date for which we have Ngram data).

To bring GRR up to date, a Google Scholar search conducted in mid-2017 turned up 164,000 hits for the term “gradual release of responsibility” in titles, articles, abstracts, books, chapters, and papers. The more restrictive term “gradual release of responsibility model” still yielded over 32,800 hits, indicating that the visual representation is also quite widely used.

A Brief History of the GRR

The Motivation for the Model

For Pearson and several of his colleagues (all but David were doctoral students when this quest began), including Jane Hansen (Hansen, 1981; Hansen & Pearson, 1983), Christine Gordon (Gordon, 1985; Gordon & Pearson, 1983), Taffy Raphael (Raphael & McKinney, 1983; Raphael & Pearson, 1985; Raphael & Wonnacut, 1985), and Meg Gallagher (Pearson & Gallagher, 1983a, 1983b), the GRR Model emerged gradually (fittingly!) from a search for some reasonable way to think about how explicit reading comprehension pedagogy could be used to respond to the startling revelations of Dolores Durkin’s (1978–1979) classic finding that in the 1970s what was going on in our schools in the name of reading comprehension was neither effective nor instructive.

FIGURE 1.1 Ngram of “gradual release of responsibility” from 1983 to 2008.

Basically, what Durkin found in her examination of over 17,997 minutes of instruction in the intermediate grades was that rather than teaching students how to understand, teachers were simply requiring students to answer questions. Comprehension instruction consisted of assessments and assignments: Teachers asked questions, and students answered them. The assumptions in this widespread default approach are (a) that students can answer the questions we ask them about the texts they read, and (b) if they cannot, they will improve their question-answering abilities if teachers just increase the amount of question-answering practice they get. The irony, of course, is that this approach simply perpetuates, perhaps even exacerbates, the gap between those who can and those who cannot answer questions successfully in the first place. Why? Because more practice allows those who can to refine their good practices and those who cannot to refine their maladaptive practices. Pearson and his colleagues were looking for an alternative to the “practice makes perfect (or imperfect)” model of pedagogy.

The Collegial Scaffolding

Fortunately for Pearson and his colleagues, others at the Center for the Study of Reading at the University of Illinois in the early 1980s shared their concern and their quest for more effective pedagogy. Most important, they encountered the work of Ann Brown and Joe Campione, who were using a Vygotskian (1978) perspective to conceptualize instruction; for them, learning occurred in the zone of proximal development (ZPD)—that magical space in which students encounter the helpful support of “more knowledgeable others,” who can assist them in progressing from what they can accomplish on their own to what they can accomplish with a little boost from their friends. Ann and Joe introduced the group to another student, Annemarie Palincsar, who was conceptualizing a dissertation (which led to the now famous pedagogical routine known as reciprocal teaching) dealing with these very issues (e.g., Palincsar & Brown, 1984; Palincsar, Brown, & Martin, 1987).

Equally as important, Ann and Joe introduced the group to the recently coined construct of scaffolding from the work of Wood, Bruner, and Ross (1976) and the dynamic assessment practices of Reuven Feuerstein (Feuerstein, Rand, & Hoffman, 1979). Along with Brown and Campione’s pedagogical research, the constructs of scaffolding and dynamic assessment were driven by the recently rediscovered Vygotskian socio-cognitive views of learning and development (Vygotsky, 1978), especially the ZPD. Scaffolding provided a powerful label for what it is that the more knowledgeable others could and should do when working in the ZPD. And dynamic assessment turned out to be a prescient way of thinking about what has evolved into formative assessment (Black & William, 1998). The key element in dynamic assessment is changing the question we ask about assessment. No longer do we view assessment as a measurement of how a child performs in comparison to the norm of similar children. Instead, in a dynamic assessment frame, we view assessment as an index of what a child can do when provided with different levels of “scaffolding.” So, the question isn’t, “Can a child can do X?” Instead, it is, “Under what conditions of scaffolding can a child do X?” This question is soon followed by, “How can I fade the scaffolds over time to lead to completely independent performance?”

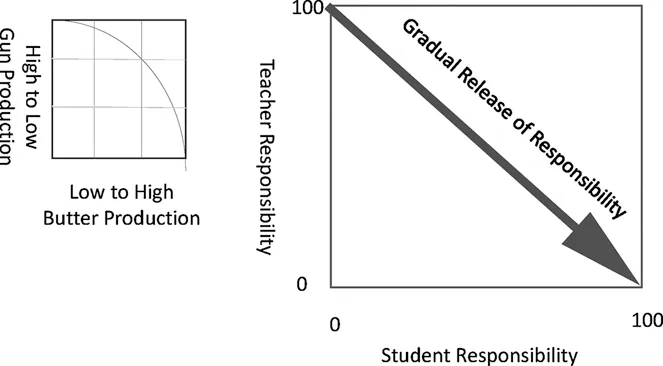

The Visual Model

The visual model evolved over time in conversations with Meg, Taffy, Annemarie, Joe, and Ann. Joe actually had a precursor visual representation that somehow displayed something like the distribution of volume of task responsibility—what proportion of the responsibility pie is each taking. And one day, the idea came to David in a noontime conversation. It was just like the classic guns and butter production function curve he had learned about in Econ 1-A at Berkeley in the early 1960s. If we can conceptualize society’s priorities as reflecting various combinations of producing food (butter) versus arms (guns), we can conceptualize comprehension task completion as requiring various combinations of student versus teacher responsibility: The more teachers do, the less students do and vice versa. So that’s how the idea of plotting teacher responsibility on the Y-axis and student responsibility on the X-axis originated. As soon as we drew a picture of it (see Figure 1.2), it all made sense to us.

FIGURE 1.2 How guns and butter inspired the “Gradual Release of Responsibility.”

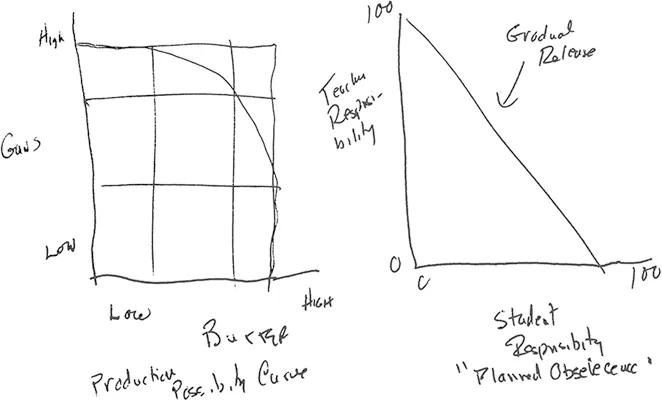

FIGURE 1.3 Facsimile of the original visual depiction of the Gradual Release of Responsibility (circa 1981 by P. David Pearson).

Of course, in those pre-PowerPoint days of the early 1980s, it did not look so polished; the original, literally drawn by David on a lunch napkin, resembled the depiction in Figure 1.3.

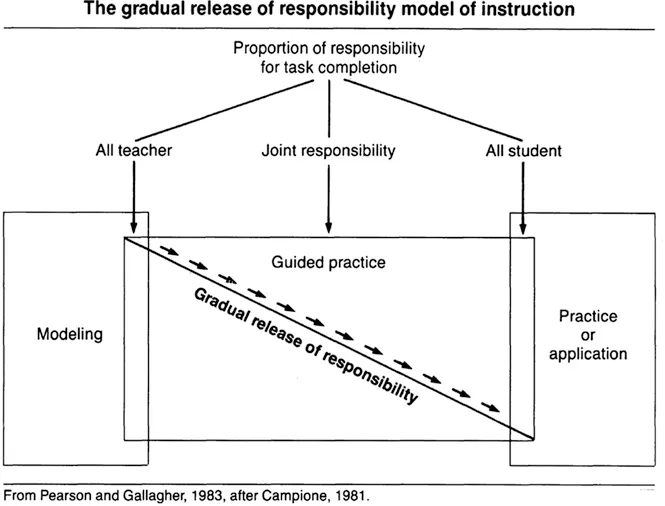

Another step forward for the GRR occurred in 1983 when David and Meg Gallagher wrote a piece for Contemporary Educational Psychology, entitled “The Instruction of Reading Comprehension.”1 Most important for GRR is that the 1983 piece included the original published version of the model, complete with an acknowledgment to Joe Campione for inspiring its creation (see Figure 1.4).

FIGURE 1.4 The original published version of the GRR Model in Contemporary Educational Psychology in 1983.

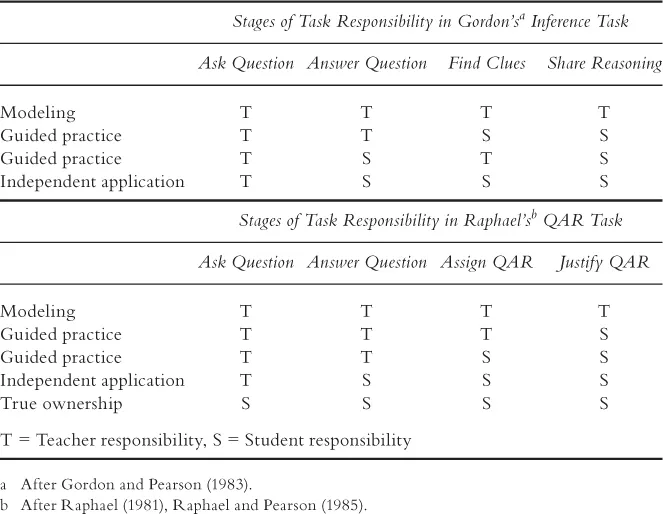

In 1985 David wrote the first of many synthesis pieces on this body of research, this one for The Reading Teacher. Entitled “Changing the Face of Reading Comprehension,” in it he unpacked the GRR more fully by illustrating the specific roles played by teachers and students in the work of Christine Gordon (Gordon, 1985; Gordon & Pearson, 1983) on drawing inferences and Taffy Raphael (Raphael & McKinney, 1983; Raphael & Pearson, 1985; Raphael & Wonnacott, 1985) on question-answer relationships (QARs). As Hansen, Gordon, and Raphael instantiated the GRR in pedagogical experiments with teachers and students, they became more specific about who did what. Table 1.1 illustrates just how the gradual release was accomplished in the work of Gordon and Raphael.

Over the years, the model has evolved and adapted to new players and new uses. But some of the key concepts from the model have survived throughout its thirty-four-year history. Among them are Modeling (a step in which the teacher—or another student—demonstrates how to do the task), Guided Practice (where the teacher and the student are sometimes jointly and sometimes separately responsible for enacting different steps in completing the task), and Independent Practice (where the teacher has, at least for the moment, completely released responsibility to the student(s)). We added a stage of True Ownership to Raphael’s QAR work because the goal was ultimately to have students generate questions. Think of true ownership as a kind of “hyper-independence.”

TABLE 1.1 Distributing Task Completion Responsibility in the Gradual Release Model

Enhancements in the Model

The model trudged along, pretty much in its classic 1983 form, for a couple of decades, but it was rendered more precise and detailed by a variety of research efforts. Two stand out in particular: reciprocal teaching (Palincsar & Brown, 1984) and transactional strategies instruction (Pressley, Almasi, et al., 1994; Pressley, El-Dinary, et al., 1992). Like Pearson and his colleagues, both Palincsar and Pressley were interested in responding to Durkin’s classic discovery of nothing instructive about comprehension; so, they focused on developing either a routine (the four strategic activities of summarizing, questioning, clarifying, and predicting in reciprocal teaching) or a menu (the list of monitoring and fix-up strategies in transactional strategies instruction). And in the process of demonstrating the efficacy of their approaches, they helped us learn even more about the key characteristics of the GRR—explicit instruction, modeling, guided practice, scaffolding, independent practice (i.e., both application and use), collaborative efforts among students, and opportunities applying the repertoir...